A Turkish doctor, Dr Ogün Erşen, who specialises in weight loss "holidays" abroad, advised an undercover BBC reporter to gain weight to qualify for gastric sleeve surgery.

Despite the reporter having a BMI within the healthy range of 24.4, Dr Erşen instructed her to "eat some snacks" to increase her BMI to 30, the required level for the surgery, an exclusive report by the BBC said.

During the consultation, no medical checks were conducted, and the reporter's BMI information was provided without actual weighing.

Dr Erşen proposed scheduling the surgery for three months later and encouraged weight gain in the meantime.

A health expert informed the BBC that urging a patient to gain weight to meet the surgery threshold is entirely unethical.

Emphasising the risks associated with irreversible surgery, the expert said that such procedures should only be done when medically necessary.

Referrals to weight management services in Scotland have surged by 96% compared to pre-pandemic levels, with NHS waiting lists for bariatric surgery exceeding four years in some regions.

While private bariatric surgery in the UK can cost between £10,000 and £15,000, booking weight-loss surgery in Turkey can be as low as £2,000.

However, a BBC Disclosure investigation has exposed unethical practices by some companies offering budget weight-loss "holidays" abroad, with Ekol Hospitals among the Turkish companies targeting British customers.

During an undercover operation at a sales day in Glasgow, Ekol was found accepting patients whose BMI did not meet the criteria for bariatric surgery.

In the UK, patients with a BMI of less than 40 and no severe co-morbidities related to obesity would typically be rejected for weight-loss surgery, however, the international IFSO guidelines set the threshold lower, at 35.

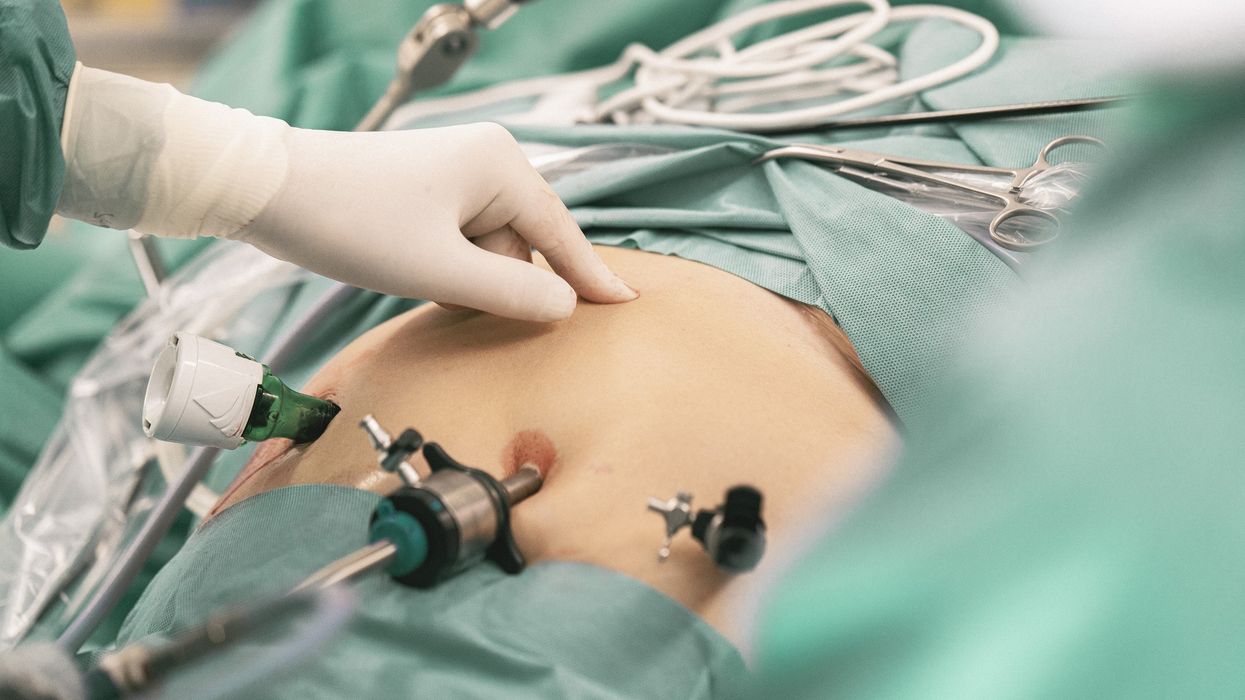

Bariatric surgery, also referred to as weight-loss surgery, is used by the NHS as a last-resort treatment for individuals with severe obesity (having a body mass index of 40 or above, or 35 plus other obesity-related health conditions).

Patients must have attempted and failed to achieve clinically beneficial weight loss through all other appropriate non-surgical methods and must be deemed fit for surgery.

The two most prevalent types of weight loss surgery include sleeve gastrectomy or gastric bypass, involving the removal of a portion of the stomach or rerouting the digestive system past most of the stomach, and gastric band, which utilises a band to reduce the stomach's size, necessitating less food to induce a feeling of fullness.

During the Ekol sales day, two undercover journalists presented false medical information that should have disqualified them.

They claimed their BMIs were 29 and 33, with one citing depression, all of which should have raised concerns for the consultant.

An Ekol sales representative also encouraged the reporter to consume more and return for surgery at a later date.

In a statement, Ekol Hospitals said, "We completely refute the suggestion that our hospital accepts patients for surgeries who do not meet international guidelines or criteria.

"Whilst at the hospital, a full and extensive health check is completed."

Additionally, Dr Erşen denied making comments encouraging a patient to gain weight.

Omar Khan, the chairman of the National Bariatric Surgery Registry and a consultant bariatric surgeon, expressed serious concerns about the consultation, describing it as "utterly indefensible."

He emphasised that it appears the surgeon is pushing the patient to meet the target for surgery, which he deems completely unethical.

Khan highlighted the importance of balancing the risks of surgery against the potential benefits of weight loss surgery, stating that performing surgery on someone who is thin is pointless as they would bear the risks without gaining any benefits.

Gill Baird, who operates a cosmetic surgery business in Glasgow, mentioned that she frequently turns away individuals for weight-loss surgery when they do not meet the specified criteria.

Baird noted that in her cosmetic surgery business, they even check for stones in patients' pockets at the scales due to instances where individuals try to make themselves appear heavier by placing weights in their pockets.

She said those who resort to such desperate measures do not fully comprehend the health risks involved.

Baird shared a tragic incident involving a UK patient who had sought a particular procedure but did not meet the criteria.

Despite being advised against it, the patient opted for a provider abroad and, unfortunately, passed away a few weeks later due to the surgery performed overseas.

This incident highlights the serious consequences of seeking weight-loss surgery outside established guidelines.