The BBC’s looking for a new diversity boss because June Sarpong is leaving the corporation. In his third and final essay, one of its former correspondents, Barnie Choudhury, suggests ways to tackle the antipathy, apparent apathy and accelerate a win in the diversity war in the corporation.

One of my favourite poems is Wilfred Owen’s Dulce et Decorum Est. It is a gut-wrenching 218-word message about the futility of war, concluding that the idea that it is sweet and an honour to die for your country is a lie. Even today, I gently, quietly weep when I read it out aloud. I mention this because when I wrote my previous two essays about diversity in the BBC, I wondered whether I had embarked on a futile mission. Why would anyone want to read my thoughts? How would my very personal stories go down? And, crucially, what was the point, what difference would one person’s lived experiences make in a battle which has been raging for at least two generations in the BBC?

I penned my thoughts because in dark corners in the BBC, we people of colour would meet and bemoan our lot in an organisation every one of us loved and yet felt betrayed on a daily basis. I wrote what I thought because former and current BBC friends and colleagues have been asking me to “say it like it is”. “You have nothing to lose”, they said mistakenly. I have everything to lose because my words can be used against me. As several told me when they read my missives, “When I say anything against the BBC to my bosses, I am considered an enemy. I am being frozen out.”

I am humbled by the response to what I have written. Please allow me to share a few words from those who have contacted me. “I just read your first essay on the BBC - nailed it,” wrote one south Asian who has truly suffered, and I have tried to help over the years. “Things got to a whole different level with abusive behaviour from a senior manager.” Another corresponded, “They still believe the whole nonsense about youth and talent. And where are all the talented POC [people of colour]? Over 35 and stuck.” I must be careful in my next example because they are very senior, and they can be easily identified. All I will say is that they recognised the idea of being hired, set up to fail, and now they are being shunned. “It’s a mess,” they write. But one of the saddest messages was from a white leader, “I was actively discouraged from helping diverse hires in case I confused them because I wasn’t their line manager.” How can that be right? Shouldn’t our default human condition be to help our fellow human beings? Every person who contacted me loves the BBC, works selflessly for the BBC, and they want the BBC, the organisation they have given their professional lives to, to succeed.

My experiences have been in one part of the BBC – the news division. I started in local radio, and, by some fluke, I ended up getting to the place many of us aspire to, network, as part of the launch team of BBC Radio 5 Live. My boss was Chris Birkett, an immensely talented guy who was my age. Like me he was a BBC trainee – but the one for leaders, rather than reporters. Boy, was he forensic, ferociously intelligent…and incredibly fair. It was an absolute joy to work with him. He got diversity, and he championed what I was trying to do – widen the appeal of the BBC to people from communities who looked like me.

Fast forward four years, and it is 1998. The head of the East Midlands in Nottingham, Richard Lucas, reached out to me. Would I be interested in becoming its community affairs correspondent? The process was tough, but I was successful. On my first day, my line manager, Emma Agnew, said to me, “Barnie, I don’t want you here…” You can imagine my concern, but she continued, “…I want to see you at network. I want you to give me two years, and I want you to work your socks off, and I’ll make it happen.”

In April 2000, I’d won two national awards, beating Five Live and Newsnight, but network turned me down for three correspondent jobs. Emma heard about it, and she rang the head of newsgathering, Adrian van Klaveren. I was in her office and could only hear her side of the conversation.

“Adrian, my boy’s just beaten your guys, and he can’t get a job at network…”

“I agree…six months then at a date of his choosing?”

With a big smile, Emma said, “OK, I’ve just negotiated a six-month attachment at network. Don’t let me down.” I like to think that I didn’t.

I tell this tale because the BBC is recruiting a “head of culture and development, BBC News”. It is a new role which will try to shift the dial on diversity and work with senior leaders to change the division’s culture. But here is the big problem. One of the biggest mistakes the BBC has made in trying to create non-white leaders is to entrust it to HR, its human resources team. Sadly, this is not just an HR problem. Another mistake is the credibility of those who’ve been appointed as diversity leads. If the gatekeepers don’t respect you, you ain’t going to get it done. The third mistake is that diversity is not a one-size-fits-all approach. BBC News is different from BBC Studios which is different from BBC Sport which is different from…you get where I’m going.

Anyone who knows anything about journalists, is that we are a sceptical bunch. We question everything, and the very best ones are those who won’t accept anything without seeing it for themselves, or at least someone they trust. Trust me when I tell you that the gatekeepers at BBC News won’t respect anyone who tries to tell them how to do their job. They won’t take orders from anyone just because it’s fashionable. And they will subvert as much as they can…while being seen to toe the company line. They will find a reason to appoint their favoured candidate. They will not appoint someone unless they want to…and it makes sense to them.

These are the challenges facing whoever is appointed. That new appointment will succeed when hell freezes over, because they will be weakened and unwittingly set up to fail before the get-go. Why? Because they must persuade the gatekeepers to buy into something in which they are not invested. These very gatekeepers have to have skin in the game. This is a huge generalisation, but all BBC News cares about is being the first, best and being able to say they did something which will get them promoted. Every single correspondent covets being on The Six and The Ten. Every editor wants to be the director of news, and every wannabe presenter wants the flagship Today programme, the Sunday morning slot and to usurp Huw Edwards.

OK Choudhury, enough already. What’s your big idea? Your honour, I point you to a strategy wot I wrote for the House of Lords media select committee.

The most important lesson for the BBC is that it needs to stop doing the same things over and over again and expecting different results. Change won’t happen. If I’ve learnt anything, it is that recruiting shining new ‘diverse’ people and putting them at the bottom rung of the ladder is a huge mistake. That is why we’re still talking about diversity two generations on. Look from within. Who have you got? The BBC has cumulatively centuries of talent already. It just is not managing that talent properly, and so they are rotting away, ignored, being made to feel they don’t count. That leads to nothing but frustration, hurt and then disappointment. It’s as if you realise that your partner has, over the years, obfuscated, deceived and serially cheated on you.

Look, as I said last week, I’ve been on two BBC schemes to fast track me for leadership. Neither worked. I was reminded several times that I was a talent and not a leader. In the end, I left the BBC and went into senior leadership for another organisation. But on every leadership course I ever attended, I was told to read Stephen Covey’s “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People”. Covey was an American educator who, through effective storytelling, set out his vision for leadership. Indeed, in every leadership interview you can bank on one question: what would you do in your first 100 days? For those applying for the vacant BBC’s diversity czar post, here are seven pragmatic steps, free of charge. Use them. Don’t use them, but don’t ever accuse me of merely criticising and not contributing to the debate.

Before I go into detail about what I would do, I need to (over)share my reasons for being such an evangelist for change. I am a child of 1970s Britain. It was a time when P-bashing was the norm and one where foreigners of a different hue were “smelly bastards who’d come to steal our jobs and women”. It was a time when, especially if you were working class, as I was, life had little to offer. It was a time when only two per cent of school leavers went to university. Many would argue that we, as a country, we, as a society, have changed very little. I disagree. On the plus side, we call out discrimination more than we did when I was a child. On the negative side, those who wish to practise discrimination do so more covertly and more cleverly. I cannot and will not put up with that.

Throughout my life, I have been blessed to meet some inspirational leaders. My thoughts are based on what I learnt from them, and others I have met on my journey.

1. Before day one, I would organise coffee with groups of department leaders one-by-one [Band E and above] to give them an active listening to. Why do they think we’re not doing as well as we might? How might we change things? What one thing could we do differently? As a senior leader, I learnt to listen, engage and create real partnerships. Your partner needs to own it.

2. Then I’d ask them to meet the survivors in two separate groups. The first would be those who have left the BBC and gone on to do better things. I’d like them to hear their stories of why they left, how they succeeded, and what were the differences between the BBC and their new ventures? The second group would be those who have been stuck in junior grades for decades. I would ask the leaders to listen to their stories, and I’d ask them to walk in their shoes. I would beg their indulgence not to be defensive or try to make excuses. Just listen, ruminate and ask one simple question: what patterns do you hear?

3. But anecdotal evidence only goes part of the way. We need to back it up with academic or scientific research. I’d hire an independent team to quiz the 100 top leaders in the corporation – how did they reach the top? What are the secrets to their success? How did the BBC, for example, have some success with women leaders and editors? Equally, what didn’t work? Look for the flaws. Is this far-fetched? No. The template exists because the BBC did this when it was criticised over its coverage of science.

4. Make it personal. Mentoring and development can only take us so far. As I experienced, we need people who believe in us and champion us. During my time advising politicians and being in the room as world history was made, I learnt that deals are made outside a meeting. They are made over breakfast, lunch and dinner. They are made at informal drinks on a lawn overlooking great vistas. They are made when each side accepts compromise and responsibility. But it all starts off with asking one question – what does success look like and what are the steppingstones to achieving it? The mayor of Bristol, Marvin Rees, was once a lowly staffer in the BBC. But the first time I met him I spotted his potential. Years later, when he was still a lowly staffer, he explained, “Barnie, the one thing the director general must do is look to those who’re making diversity happen and ask why, then reward them. Hold them up for all to see and share best practice.” You have to ask, don’t you, how on earth did the BBC miss such a huge talented leader when he was staring his bosses in the face? For what it’s worth, I’d make culture and diversity part of a leader’s annual appraisal. I’d set clear KPIs and steppingstones so there is no confusion about what we expect.

5. Data matters. We need to monitor constantly. That’s why we need a dashboard. This is 2022, and we must be able to come up with a system whereby we know at any given moment the diversity statistics rather than current practice of analysing them just for annual reports.

6. Take creative risks, and above all be kind. No-one comes into work to fail. Allow them the chance to fail creatively. Think the unthinkable – give the diversity czar commissioning powers. Allow them to set up and run training and development courses. The model I would use is sport. It sounds mad, but it really isn’t. How do athletes, footballers, and tennis stars win Olympic gold or become world champions? Everyone has his or her own challenges. And yet while training, the team continually assesses, adapts and visualises its way to sporting success. Their coaches don’t set champions up to fail. In short, how do other organisations do it? Teach them the rules of the game. And for goodness’ sake, own your mistakes. Gareth Southall’s acceptance that he carried the can when three black players missed penalties in the Euros remains an exemplar of true leadership.

7. Finally, remember it is all about story telling. The narrative arc. The journey. Tell stories. Market your successes. If it’s good enough for the Harvard Business School, which teaches through case studies, then it’s good enough for me. We need to evangelise and prove this is not a “woke culture”. It’s our culture. Who are our success stories and what are they going to give back? That’s how we truly change culture in an organisation.

I have decided to provide pragmatic solutions because I don’t want the words of my previous two essays to be taken out of context, and to put another nail in the coffin of the organisation this government is bent on destroying. Let me stress again, culture secretary, your will not succeed in your war against the BBC. The ballot box is our way of ensuring democracy in a country which, on the whole, plays fairly. The state does not fund the BBC. I, and 25 million others, choose to do so. I know we think the licence fee is a mandatory tax. But if you choose to own a TV set and want to watch live programmes then you must pay 44p per day for a privilege, and it is a privilege. I know many who have opted out and decided that they can live without watching BBC television. But lest we forget, for 44 pence we get impartial news, sport, drama and culture – things which define a democratic society where governments trust their people. Think China, Russia, North Korea, Iran and Afghanistan – are you sure you want to sleepwalk to fake-state-sponsored-brain-washing-news?

To be clear, my three essays can be boiled down into one phrase, which even Boris Johnson and Jacob Rees-Moggs can understand: heroibus pugna pro diversitate – heroes fight for diversity.

Read Part 1: https://www.easterneye.biz/why-is-the-bbc-failing-when-it-comes-to-diversity/

Read Part 2: https://www.easterneye.biz/bbc-is-not-able-to-move-the-dial-on-diversity/

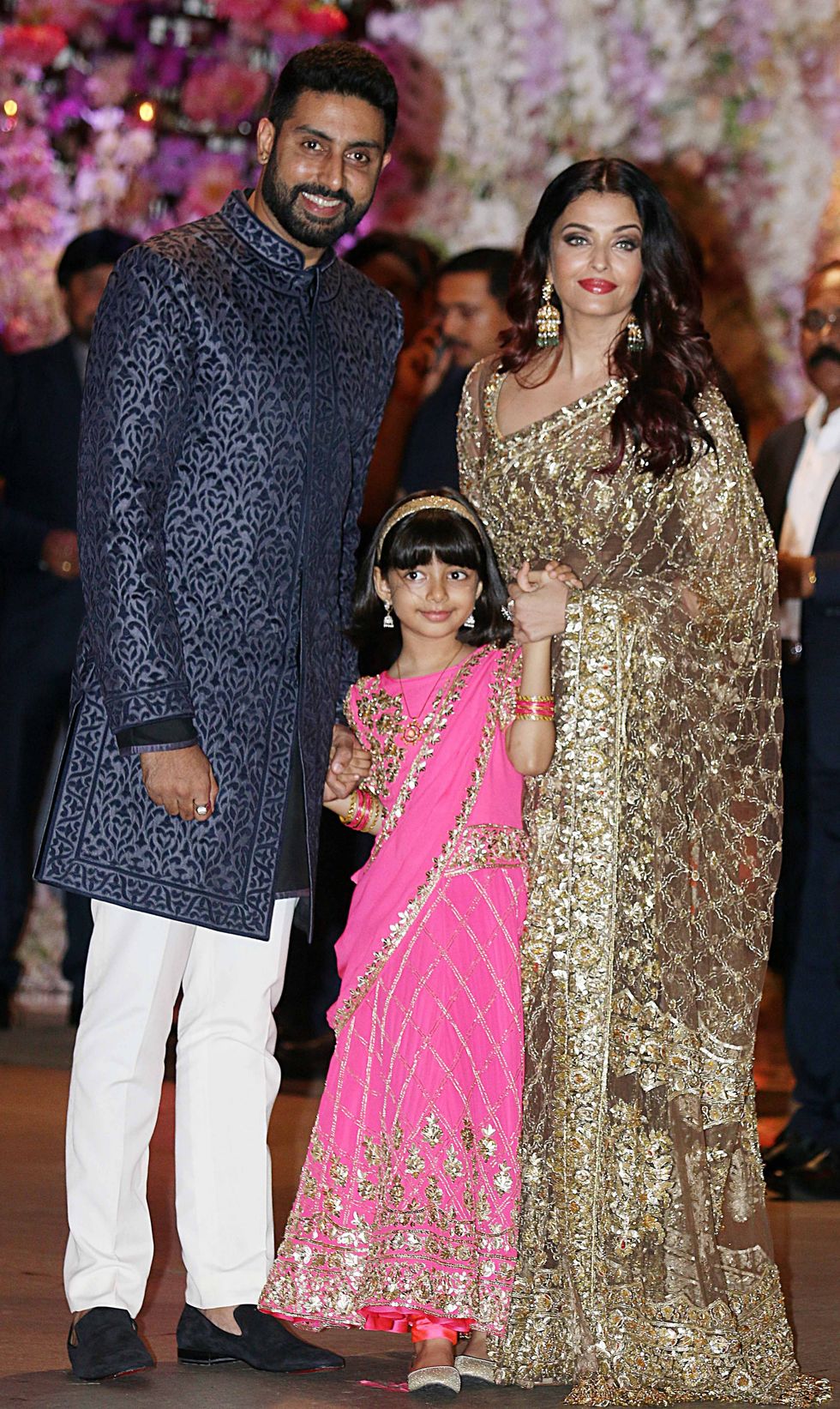

Aaradhya Bachchan has no access to social media or a personal phoneGetty Images

Aaradhya Bachchan has no access to social media or a personal phoneGetty Images  Abhishek Bachchan calls Aishwarya a devoted mother and partnerGetty Images

Abhishek Bachchan calls Aishwarya a devoted mother and partnerGetty Images Aaradhya is now taller than Aishwarya says Abhishek in candid interviewGetty Images

Aaradhya is now taller than Aishwarya says Abhishek in candid interviewGetty Images Aishwarya Rai often seen with daughter Aaradhya at public eventsGetty Images

Aishwarya Rai often seen with daughter Aaradhya at public eventsGetty Images

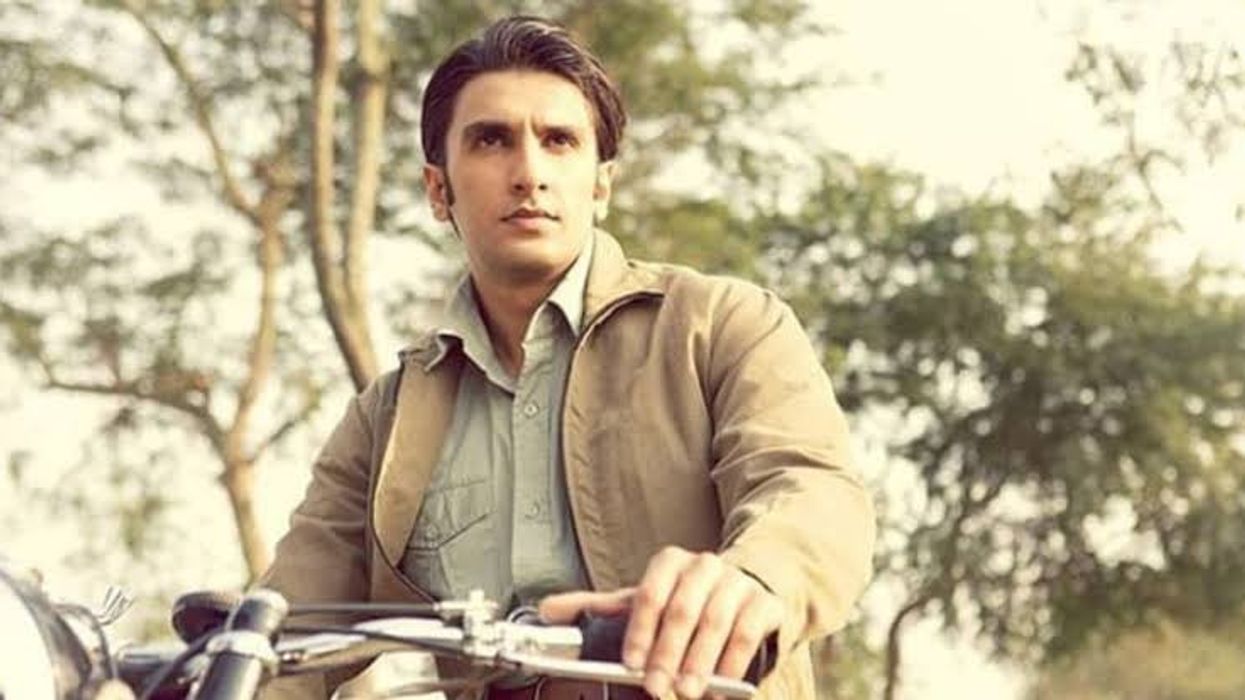

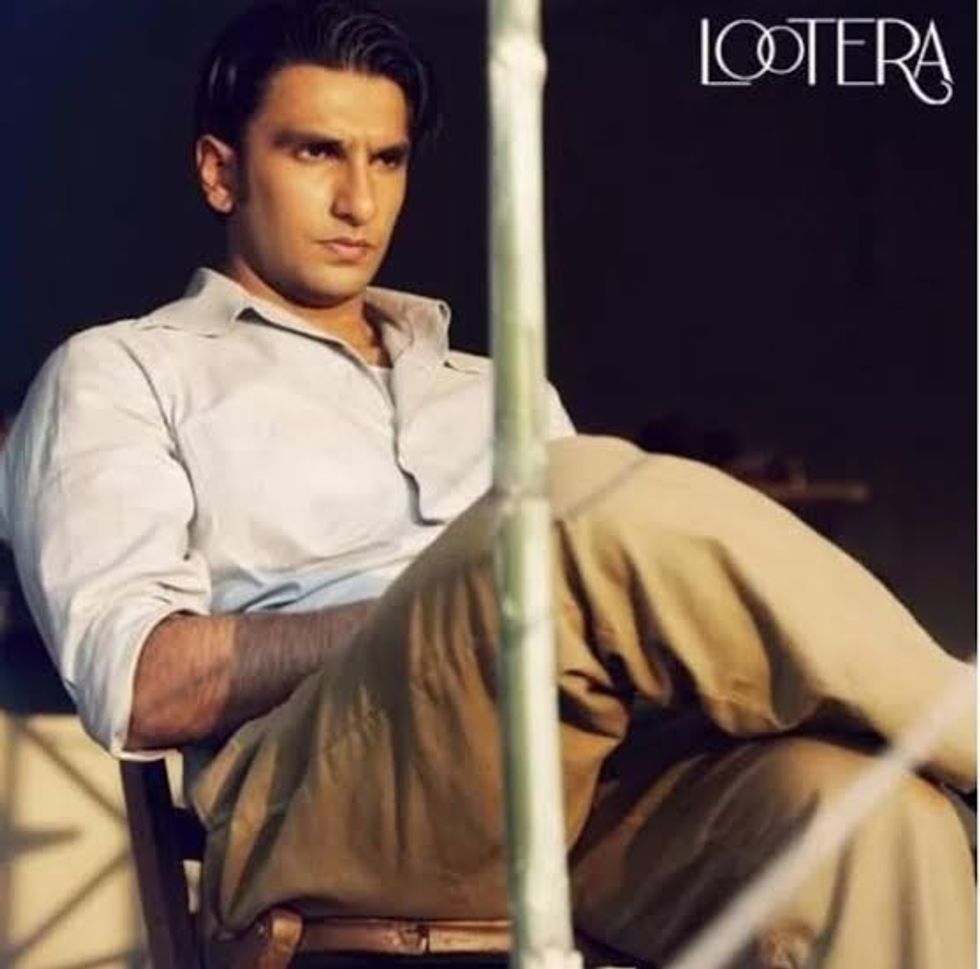

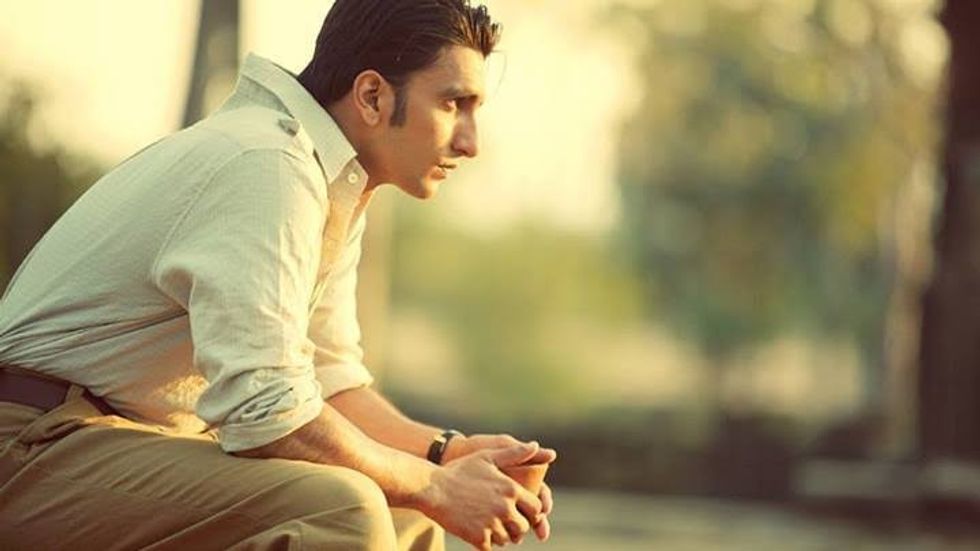

Lootera released in 2013 and marked a stylistic shift for Ranveer Singh Prime Video

Lootera released in 2013 and marked a stylistic shift for Ranveer Singh Prime Video  Ranveer Singh’s role as Varun showed he could command the screen without saying much

Ranveer Singh’s role as Varun showed he could command the screen without saying much The period romance Lootera became a turning point in Ranveer Singh’s career

The period romance Lootera became a turning point in Ranveer Singh’s career Ranveer Singh’s performance in Lootera was praised for its emotional restraint

Ranveer Singh’s performance in Lootera was praised for its emotional restraint Ranveer Singh and Sonakshi Sinha starred in the romantic drama set in 1950s BengalYoutube/Altt Balaji Motion Pictures

Ranveer Singh and Sonakshi Sinha starred in the romantic drama set in 1950s BengalYoutube/Altt Balaji Motion Pictures  Lootera’s legacy has grown over the years despite its modest box office runYoutube/Altt Balaji Motion Pictures

Lootera’s legacy has grown over the years despite its modest box office runYoutube/Altt Balaji Motion Pictures