AS A turquoise tsunami broke across the county councils of England, sweeping the Conservatives out of local power everywhere, Nigel Farage – rather than Sir Keir Starmer or Kemi Badenoch – is clearly making the British political weather.

The political future has rarely seemed so unpredictable. Yet there were several precedented echoes of past Farage breakthroughs too.

This was the third time in just over a decade that a Farage-led party has topped the polls, having won the 2014 and 2019 European elections with Ukip and the Brexit Party. These are all what academics call “second order elections”, where voters often decide to ‘send a message’ about national politics, rather than focusing on who to elect to the roles on the ballot paper.

Despite the sweeping gains in seats, there were not many first-time Farage voters this spring. About 1.6 million people voted Reform last Thursday (1) – about one in 10 of those eligible to vote, or around a third of the votes cast by the third of the electorate who habitually vote in local as well as national elections.

That only half as many people tend to vote as in a general election helps Reform – skewing the local electorate to be older, less ethnically diverse and more socially conservative than those who come out in a general election. Most of those who voted Reform last week would have been among the five million voters for the Brexit Party in the 2019 European elections, when the Tory vote fell to just nine per cent.

A local election breakthrough raises the stakes more than winning European elections. Few people expected MEPs elected for a get-out-of-Europe party to do much work in Brussels. Reform voters may expect more from those in charge of local government. Six hundred and seventy seven councillors could give Reform a significant local base, but they face a steep learning curve. Reform’s populist appeal involves a largely performative politics. Much of local government is about meeting statutory responsibilities.

“We need to be realistic about what we can and can’t do”, Reform’s David Wimble told the BBC. “Somebody stopped me today and said, ‘when are you going to stop the boats then?’ But this is the county council.”

‘Stop the Boats’ was on Reform’s Kent election leaflets, where Wimble is among six out of 57 new Reform county councillors who have prior experience. His post-election expectation management was directed as much to his colleagues as their voters.

Reform’s new Lincolnshire mayor, Andrea Jenkins, has proposed housing asylum seekers in makeshift tents. Yet Kent County Council has a key frontline responsibility to look after unaccompanied children who claim asylum. Will Farage’s claims about an over-diagnosis of autism see Reform councils deprioritise special educational needs? Reform’s voters will include parents struggling for support.

Politically, these are terrifying results for the Conservatives, finishing fourth in the ballot, with the lowest vote – in opposition to an unpopular government – of either major party since records began, with more losses to the LibDems too. The bookmakers now give Badenoch only a one-infour chance of surviving as leader to a general election, suggesting the party may gamble again on choosing its sixth new leader since 2016.

But there was more hope for Labour from the other side of the world this weekend. Last year was one of anti-incumbency in elections around the world. This year has seen centreleft politicians get re-elected by challenging their national opponents as too close to the spirit of Donald Trump.

The victory of Canada’s Mark Carney has been followed by the surprisingly decisive re-election in Australia of Anthony Albanese. The bespectacled 62-year-old pragmatist, criticised for his lack of rhetorical flourish, is the most Starmer-like politician on the world stage.

Australian opposition leader Peter Dutton lost his own seat, just as Canadian Conservative Pierre Poliviere had last month. Both defeated leaders proposed faster cuts in immigration as key campaign themes, but struggled when pressed over whether their numbers added up.

The Canadian Liberals and Australian Labor party have, like Starmer, proposed to manage net migration levels down from record levels – but took the argument to their opponents for having unworkable and damaging proposals. They won not by echoing their populist opponents but rather by uniting the anti-populist vote.

Could Farage be our next prime minister? Reform can now claim it is far from unthinkable. But that very ‘thinkability’ may prove Farage’s biggest barrier once voters need to choose a government, given his polarising reputation and Brexit’s fading appeal. In five years’ time, might the post-poll inquests even see Farage’s local election breakthrough as Starmer’s secret weapon? Perhaps. But voters do not face that election for four years.

Rather than chasing Farage’s insatiable populist core vote, the prime minister must show how to build a record in government if he wants to try to make the political weather too.

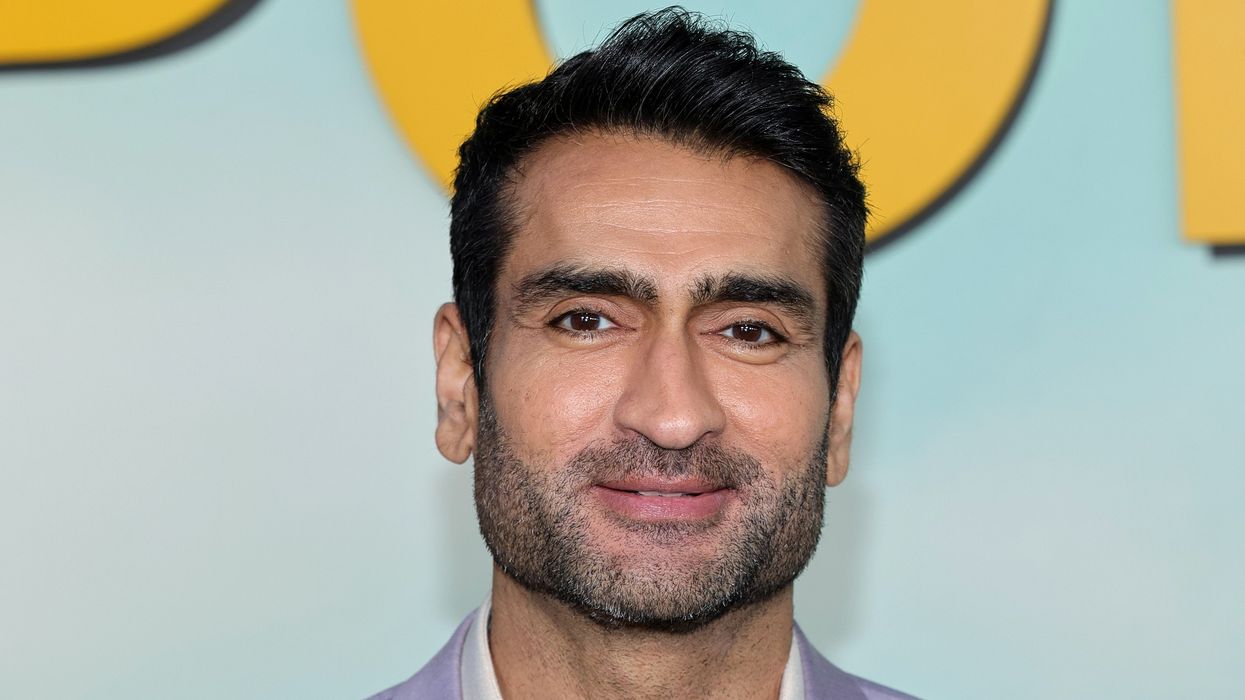

Sunder Katwalawww.easterneye.biz

Sunder Katwalawww.easterneye.bizSunder Katwala is the director of thinktank British Future and the author of the book How to Be a Patriot: The must-read book on British national identity and immigration.