THE chief executive officer of the John Lewis Partnership, Nish Kankiwala, revealed that an underdog mentality has seen him continually overcome the odds and transform the fortunes of some of the biggest companies in the world.

In his time as John Lewis’s first-ever CEO, Kankiwala has played a key role in bringing the group back into profit after it suffered significant losses due to the pandemic and cost of living crisis.

His appointment in March 2023, however, was met with scepticism, with critics claiming he would struggle in retail after spending most of his career in the fastmoving consumer goods (FMCGs) sector, as part of brands such as Hovis, Burger King and PepsiCo.

“I love being the underdog,” Kankiwala told an audience at the Asian Business Awards last Friday (15).

“When I ran the Burger King business with 4,000 restaurants worldwide, somebody said, ‘well, McDonald’s is the number one. When I ran PepsiCo, somebody said, ‘Coca Cola is number one’. It was the same when I ran Hovis.

“It’s always that element of being the underdog, being the one that nobody believes can actually win. And when you have that, you want to prove everybody wrong and turn businesses around.

“When I took John Lewis, there was a real view that I didn’t have the skills, nor did I have the ability to turn it around. While I had a view as to how I could do it, it’s fundamentally the sheer determination to prove people wrong.”

In October, it was announced that Kankiwala will leave his position as CEO and revert to being non-executive director in March 2025. The move is to support the new chairman, former Tesco UK boss Jason Tarry, who succeeded Dame Sharon White last month.

The Partnership, which owns the Waitrose supermarket chain and 34 department stores, said the role of chief executive will not be directly replaced, and reflects the “significant progression of the transformation” of the business.

“I was delighted to agree to take on the role for a two-year period during this time of pivotal change. Since then we’ve refreshed our Partnership strategy to be rooted in retail; significantly improved our cash flows to enable record investment for growth; and returned the Partnership to full-year profit,” said Kankiwala.

The 66-year-old reflected on his upbringing when looking at where he got his fighting spirit and his desire to prove people wrong.

His family came to the UK from Mumbai, India, in the 1960s. At first his parents couldn’t afford for Kankiwala and his sister to come to London with them, so they stayed with their grandparents, who had six sari shops.

When they did join their parents in the UK, circumstances meant they had to move regularly and often with little notice.

“My mother and father came over for a better life, but had no real money,” he said. “Every few months we would get moved on because obviously we were slightly the ‘wrong hue of colour’.

“My mum had this trick of making sure the masalas we needed to make the saag in the evening was in one dabba (container), and then all the other stuff would be in a suitcase and we would be ready to move that afternoon.

“We moved around a lot because the landlords normally kicked us out. It was a rotating set of housing conditions.”

At the time, the migration from East Africa hadn’t happened yet so the Kankiwalas were one of the few Asian families in Walthamstow, north London.

After a while, though, his friends “forgot his colour” and they bonded over their love of Tottenham Hotspur football club.

However, racism reared its ugly head again when families of south Asian heritage started arriving in the UK from Kenya and Uganda.

When some of his friends said they wanted to send these families “back home” because they were “not from this country”, Kankiwala explained that he too was not from ‘this country’ and he had also come from India.

Their response was an eye-opener for the young Kankiwala, he admitted.

“‘Yeah, but you’re one of us,’ they said. That’s when I realised something had happened – we had integrated.

“We all worked – my dad worked at British Gas as an accountant, my mum was a secretary and I worked at a store in Walthamstow market and stacked tins of beans at Tesco on a Saturday.”

Kankiwala kept that work ethic throughout his career and continued to graft and claw his way up the career ladder.

After reading chemical engineering at university, he was all set for a position at BP before a chance encounter saw him shift career paths and become a management trainee at Lever Brothers.

“My first job was selling soap powder,” he said.

“In those days, we used to sell Persil out the back of a Passat estate and your bonus was based on how much you sold. That’s how I started, as a sales rep – selling soap powder.”

Kankiwala described his 15 years at Unilever and 10 years at PepsiCo as his “schooling” in how to turn businesses around. He spent part of his time at PepsiCo under the tutelage of Indra Nooyi, saying: “You either learned something from Indra or you were basically out, so I thought I’d better learn something.”

In his 20 years of turning around businesses, Kankiwala said what he has learned was that the key to success was speaking to customers, rather than relying on data and analysis.

Data and AI should be an “enabler and enhancer of human instinct”, he said.

“The closer you get to the point where you’re talking to a customer is when you get to know the real truth,” he said.

“I can give you many examples. Whether it’s Hovis or Burger King or parts of PepsiCo or even John Lewis, it’s the essence of having the truth of what a customer actually believes is true, and most corporations tend to mask that with data science and gobbledegook.

“I’m a firm believer that is the point that makes the difference in a turnaround. Most turnarounds fail because they don’t actually understand the true essence of what a customer actually wants.”

When Kankiwala took over a struggling Hovis, he was told by the team that they had the best quality bread in the country and all the data proved it. But when he spoke to customers, they said they didn’t believe that.

“We soon realised that internally, we measured everything about bread – the colour, size, all those great things. But what we forgot is that customers don’t actually eat bread. They eat toast, and they eat sandwiches.

“The fundamental difference I made in that business is I bought everybody a toaster and from that point onwards, we chose quality by how bread was actually consumed as compared to how bread was actually made.

“And then over seven years, we became the fastest growing bread company in the UK, and we sold that business to another private equity firm.

“It’s moments like that that really strip away the myths and the data that really cloud the issue. And it takes that essence of being honest about what the customer really wants and how the customer sees the product.”

Kankiwala also reflected on how second and third-generation Asian entrepreneurs such as himself were shaped by the lives of their parents.

“Look at the amazing success in this room. There’s £160 billion of wealth here. I think for all of us, at least certainly for me, it’s always been about the fact that I know I can do better than this, whatever this is. I know there’s another this that goes past it,” he said.

“It’s been sort of instilled in me when I saw my mother and father strive. We didn’t have a house until really late and then we bought our first shop. But it was always about, I know I can do better tomorrow than I did today.

“Still to this day, I fundamentally believe that, which is, there’s always something better.”

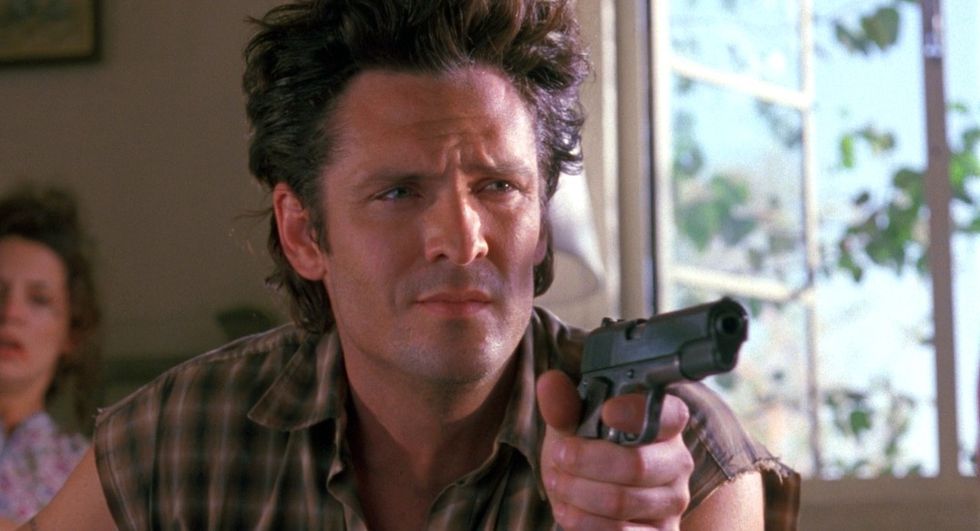

Reservoir Dogs

Reservoir Dogs Michael Madsen as Budd aka SidewinderIMDB

Michael Madsen as Budd aka SidewinderIMDB Thelma & LouiseIMDB

Thelma & LouiseIMDB Free WillyIMDB

Free WillyIMDB  Donnie BrascoAlex on Film

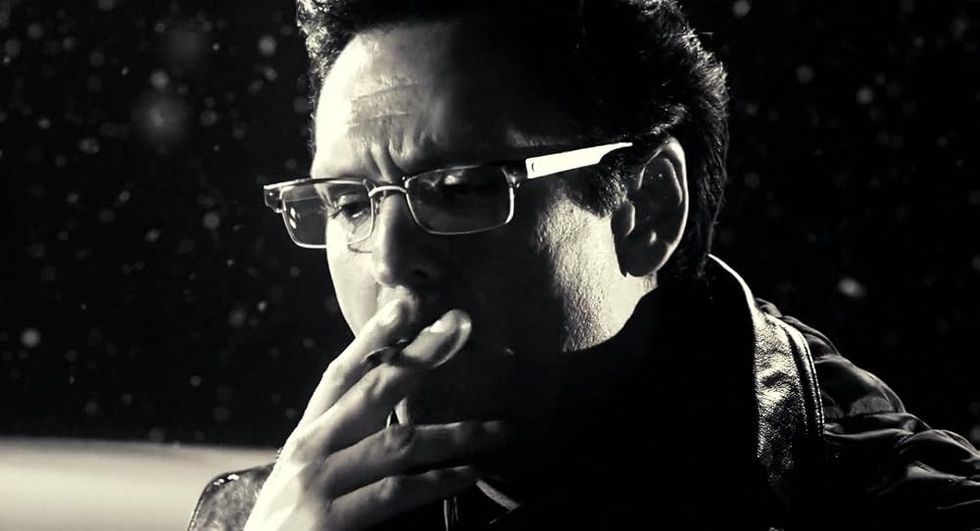

Donnie BrascoAlex on Film  Sin CityIMDB

Sin CityIMDB  The Hateful Eight IMDB

The Hateful Eight IMDB Mulholland FallsVirtual History

Mulholland FallsVirtual History  Kill Me Again

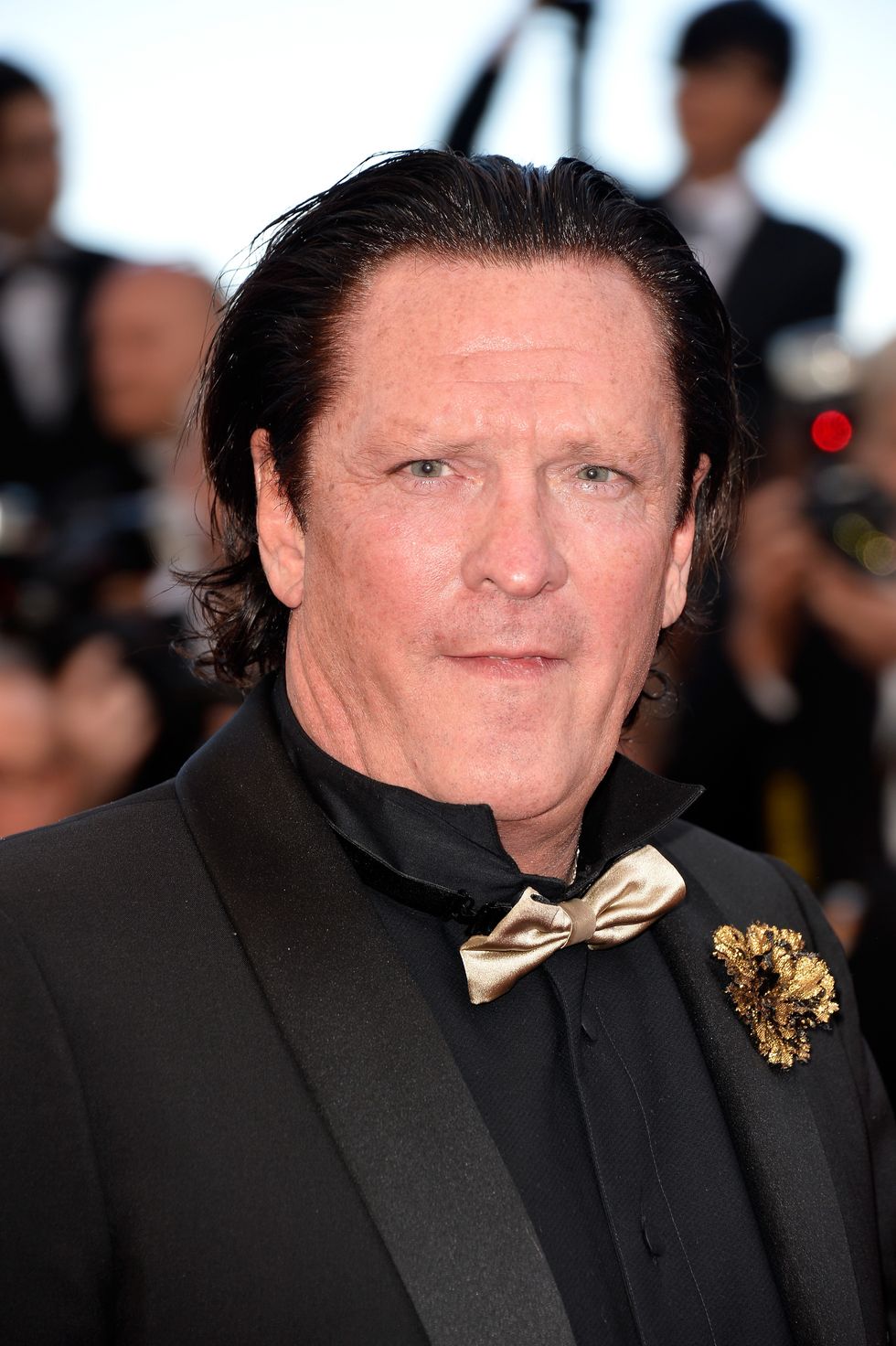

Kill Me Again  Michael Madsen attends the Closing Ceremony and Fistful of Dollars Screening Getty Images

Michael Madsen attends the Closing Ceremony and Fistful of Dollars Screening Getty Images

Katy Perry Orlando Bloom Choose Co Parenting Future After Nine YearsGetty Images

Katy Perry Orlando Bloom Choose Co Parenting Future After Nine YearsGetty Images  Katy Perry and Orlando Bloom focus on raising their daughter with love and respect Getty Images

Katy Perry and Orlando Bloom focus on raising their daughter with love and respect Getty Images  Katy Perry and Orlando Bloom end their long running romance and plan to raise their daughter together as a family

Katy Perry and Orlando Bloom end their long running romance and plan to raise their daughter together as a family