It was in Hampstead, north London, that the artist Lancelot Ribeiro settled and called his home.

Ribeiro, whose family was from Goa, was born in Bombay in 1933. He arrived in bomb-damaged Britain in 1950 having followed the journey of his half brother Frances Newton Souza, a renowned painter.

An exhibition of his works, featuring paintings with bold outlines depicting church spires, domes and townscapes in an expressionistic style, was recently launched as part of the year-long project celebrating Indian culture.

For his daughter Marsha Ribiero, the exhibition in London’s Burgh House is personal and poignant, and one which she helped to curate six years after his death. As she guides me through the compact space with a sense of pride on a cold November afternoon, she points out wooden toy blocks displayed in a glass cabinet which Ribeiro made for his children nestled among photographs and memorabilia.

Receptacles made from grasses picked by his daughters during walks on the heath also feature in the gallery.

“We wanted to give a flavour of how prolific he was and how he varied in style. He was very well known in the 1960s in India for his small impressionist townscapes. What I’ve been trying to do since his death is to show that he’s constantly been experimenting and reinventing himself throughout the years,” says Marsha.

Calm watercolour nature scenes hang on the gallery walls in contrast to the frantic dark cityscapes and frenzied figures painted in oils.

In the early 1960s, Ribeiro began experimenting with what was then an industrial solvent called PVA – which he would mix with oil paint giving his works a textured sheen. It became a forerunner to acrylics.

Not only did he paint, but he also produced ceramics and wood sculptures, and was known for being restless and compulsive.

Arriving in Britain as a teenager, Ribeiro was sent to study accountancy by his father but the life of an artist beckoned when he began life drawing classes at St Martins School of Art.

He was then called up for conscription, and he carried out a short stint in the Royal Air Force before being given compassionate leave.

On his return to India for a short period, Ribeiro began writing poetry and painting. Soon a string of successes followed his first sell-out exhibition in Bombay in 1961, gaining him considerable attention.

A year later, he settled in Britain and established his studio in Belsize Park, exhibiting in some of London’s leading art galleries. Marsha explains that her father lived through turbulent times through history when borders were changing.

The exhibition reveals the racist abuse he received, having been assaulted in London soon after he arrived in the UK. This incident spurred him on to form a group for Indian artists to try and break down the barriers they were finding in the British art scene, including prejudice, marginalisation and type casting.

“It was seminal in bringing Indian art to where it is today,” says Marsha.

The collective once stormed into the office of a junior official at India House and demanded they put on a show.

“They were trying to awaken the cultural departments to say, ‘here are artists who have assimilated their experiences from being in Europe coming from a rich civilisation who need to be noticed’,” Marsha explains.

In 1980, the artist sought to bring the Arts of India to Burgh House where his creations hang today.

Marsha is now involved in a film project looking at issues that affected her father and how they resonate today.

Retracing Ribeiro runs until March 2017. Go to www.burghhouse.org.uk for more information.

Saif Ali Khan’s royal inheritance in Bhopal declared enemy property after court verdictGetty Images

Saif Ali Khan’s royal inheritance in Bhopal declared enemy property after court verdictGetty Images  Saif Ali Khan with family Getty Images

Saif Ali Khan with family Getty Images An exterior view of the Noor Us Sabah Palace now listed under enemy property Getty Images

An exterior view of the Noor Us Sabah Palace now listed under enemy property Getty Images Saif Ali Khan loses claim to Pataudi family properties as court cites Pakistan connectionGetty Images

Saif Ali Khan loses claim to Pataudi family properties as court cites Pakistan connectionGetty Images

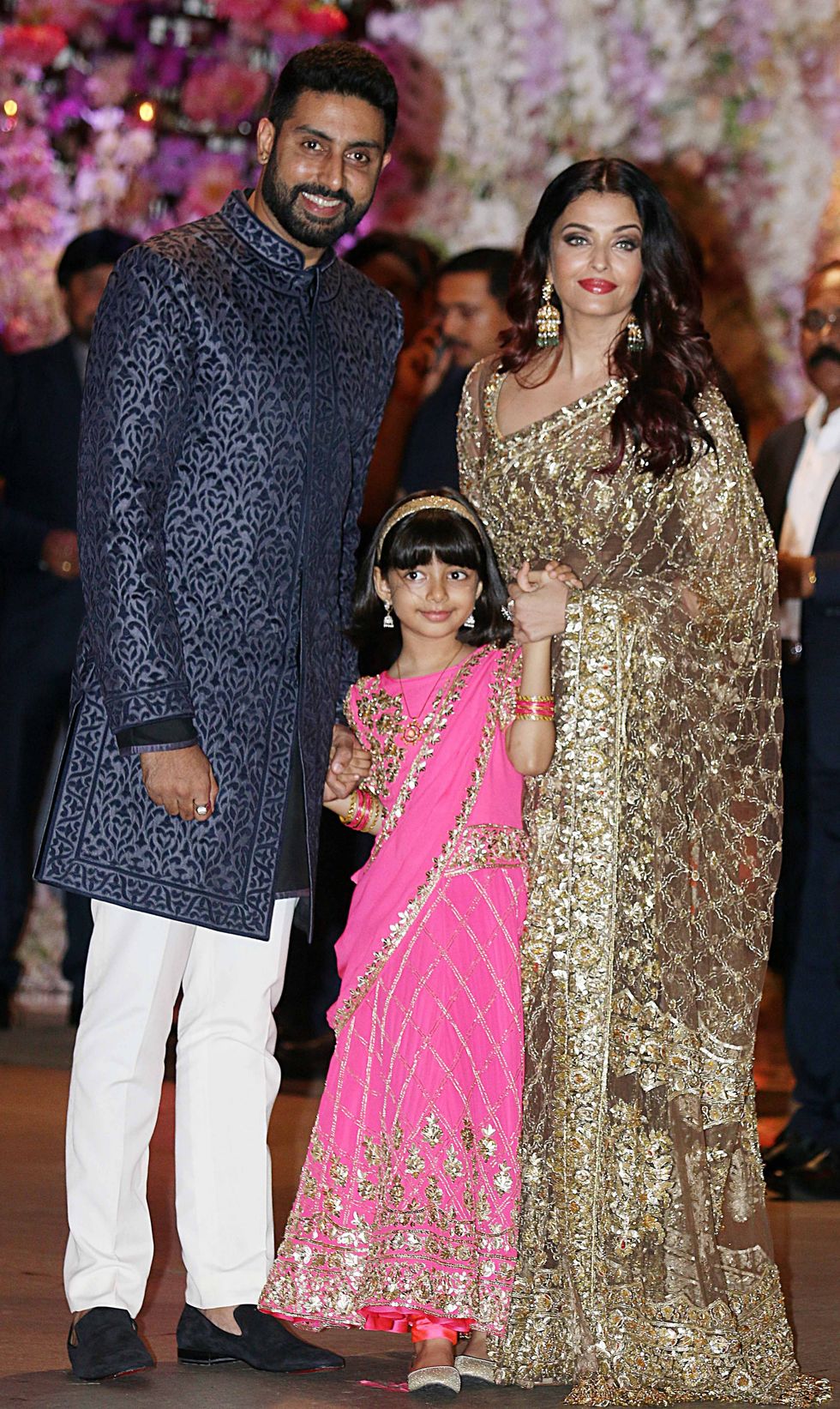

Aaradhya Bachchan has no access to social media or a personal phoneGetty Images

Aaradhya Bachchan has no access to social media or a personal phoneGetty Images  Abhishek Bachchan calls Aishwarya a devoted mother and partnerGetty Images

Abhishek Bachchan calls Aishwarya a devoted mother and partnerGetty Images Aaradhya is now taller than Aishwarya says Abhishek in candid interviewGetty Images

Aaradhya is now taller than Aishwarya says Abhishek in candid interviewGetty Images Aishwarya Rai often seen with daughter Aaradhya at public eventsGetty Images

Aishwarya Rai often seen with daughter Aaradhya at public eventsGetty Images

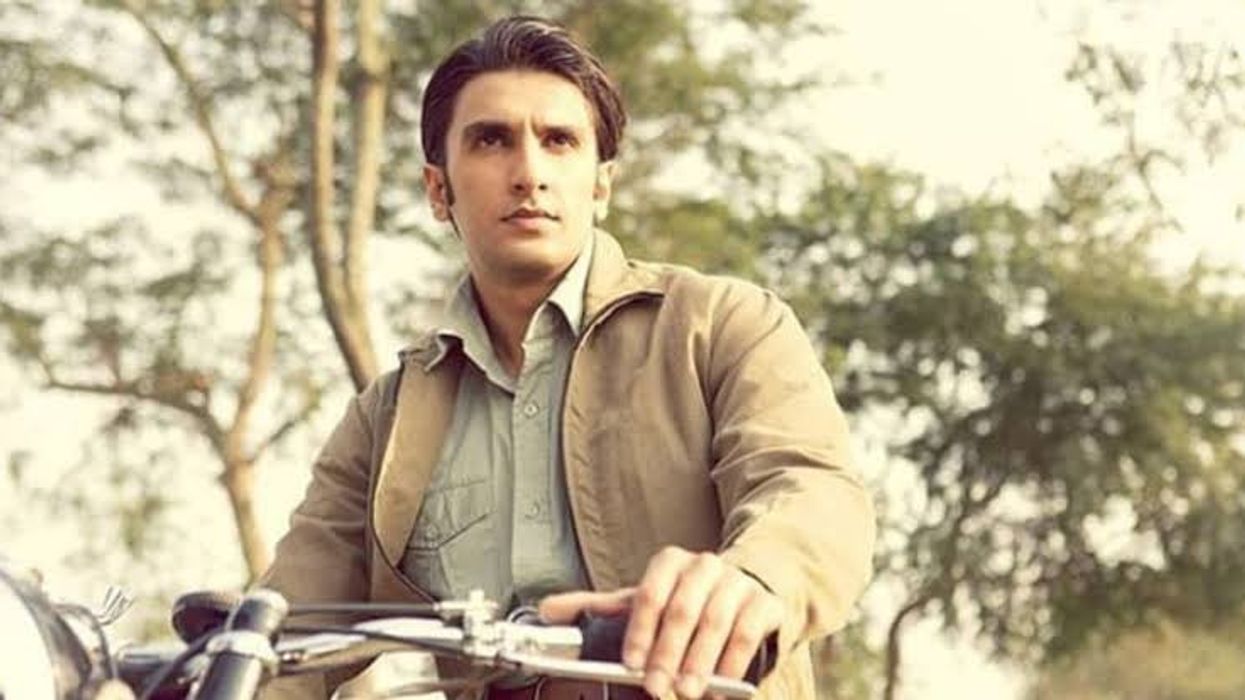

Lootera released in 2013 and marked a stylistic shift for Ranveer Singh Prime Video

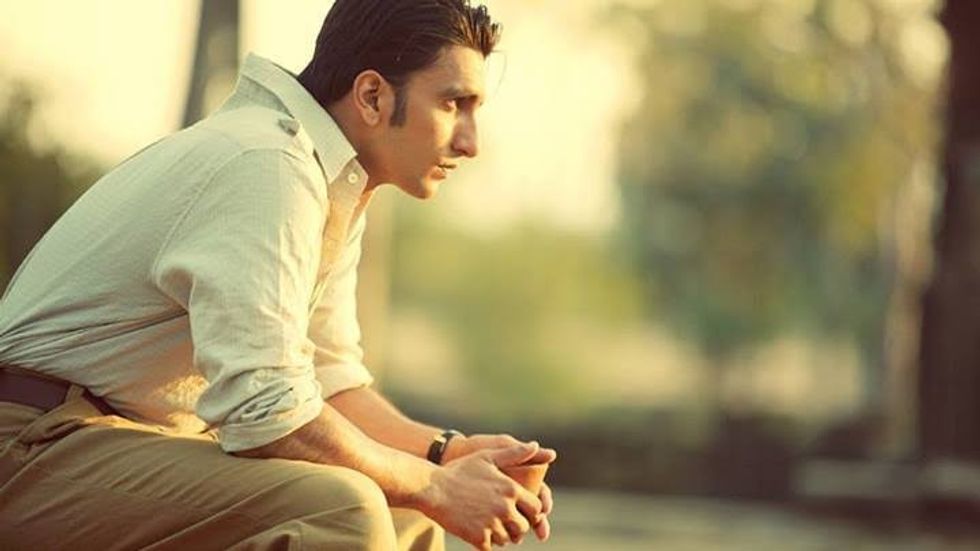

Lootera released in 2013 and marked a stylistic shift for Ranveer Singh Prime Video  Ranveer Singh’s role as Varun showed he could command the screen without saying much

Ranveer Singh’s role as Varun showed he could command the screen without saying much The period romance Lootera became a turning point in Ranveer Singh’s career

The period romance Lootera became a turning point in Ranveer Singh’s career Ranveer Singh’s performance in Lootera was praised for its emotional restraint

Ranveer Singh’s performance in Lootera was praised for its emotional restraint Ranveer Singh and Sonakshi Sinha starred in the romantic drama set in 1950s BengalYoutube/Altt Balaji Motion Pictures

Ranveer Singh and Sonakshi Sinha starred in the romantic drama set in 1950s BengalYoutube/Altt Balaji Motion Pictures  Lootera’s legacy has grown over the years despite its modest box office runYoutube/Altt Balaji Motion Pictures

Lootera’s legacy has grown over the years despite its modest box office runYoutube/Altt Balaji Motion Pictures

AR Rahman confirms collaboration with Hans Zimmer on InstagramInstagram/

AR Rahman confirms collaboration with Hans Zimmer on InstagramInstagram/

Ozzy Osbourne to perform one final time in BirminghamGetty Images

Ozzy Osbourne to perform one final time in BirminghamGetty Images  Ozzy Osbourne and Black Sabbath reunite in Birmingham for farewell concert after two decades Getty Images

Ozzy Osbourne and Black Sabbath reunite in Birmingham for farewell concert after two decades Getty Images