Packaging soft-focus romance within a rigid frame of patriarchy, the Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge love story unfolded in grassy Swiss meadows and Punjab's mustard fields 25 years ago and went on to become a cult classic that combined desi sensibilities with NRI sensitivities.

The film, one of India's most successful, put Shah Rukh Khan and Kajol right up there as among Bollywood's most popular onscreen pairs down the decades. It has withstood the test of time, with many viewers going back to rewatch it, and its love story is still fresh but also anachronistic and out of sync with contemporary realities, say some.

The Raj-Simran romance drama not about lovers who dare all but more about conformists who love each other desperately and will get married only with their parents' concurrence released on October 20, 1995.

And India woke up to romance DDLJ' style, where the boy and girl, both London bred but Indian' at heart, barely hold hands, quite unlike the bolder, franker portrayal of relationships in Hindi cinema today.

The film centres around Raj, the carefree, rich boy who falls in love with Simran, the dutiful daughter getting ready to marry a man she has never met, in Europe. They live out the teen dream of holidaying in the continent but Simran returns home to London and then to a village in Punjab where her father has arranged a match for her. Lovelorn Raj follows her there but resolves not to marry her till her strict father approves.

DDLJ is all about large-hearted non-resident Indian desis and their Indianness, shot in breathtaking locations with a soundtrack by Jatin-Lalit and Anand Bakshi to suit every mood and dialogues that went on to become even more popular in the digital age.

Twenty-five years later, audiences still watch the film at Mumbai's Maratha Mandir till COVID-19 struck in March this year but the views are as diverse as the first half of the film in London and Alpine locales from the second in a rambunctious family in a Punjab village.

According to senior film critic Saibal Chatterjee, the movie inaugurated "the era of the designer film made for NRIs".

DDLJ marked the directorial debut of Aditya Chopra, son of veteran filmmaker Yash Chopra, known as the 'King of Romance' in Hindi cinema. The 1995 film, also starring the late Amrish Puri, Farida Jalal and Anupam Kher, released at a time when India had opened up to liberalisation.

Chatterjee said the film looked fresh then but packaged old ways of living in a new sheen.

"It was about an NRI couple who live by their own rules, but at heart are completely Indian," he told PTI.

According to Chatterjee, DDLJ comes only after the 1975 hit Sholay for the influence it exercised on Hindi cinema.

"It is one of Hindi cinema's biggest commercial hits. So much has changed with the arrival of streamers, but Maratha Mandir theatre was still running it until COVID-19 happened."

An entire generation of viewers has grown up in the last two decades but for some, the relevance of the film is based on that one vivid memory of when they first watched the film.

Prema Maharish, 84, remembers going to see the film in a Mathura hall and remembers the dialogues verbatim. Her particular favourite is the stern father letting go off Simran's hand in the climax with these words, Ja Simran Ja. Jee le apni zindagi. (Go Simran, go live your life). And the young woman, having finally got her father's permission, runs towards the train picking up pace as it pulls out of the platform to hold Raj's extended hand.

"One thing that seemed off to me even then was why Shah Rukh didn't pull the chain to stop the train. What would have happened had the train left the station without Kajol? Kajol had to run too much," the Mathura-based former school principal said about the much-debated climax sequence.

The film is a perfect blend of fairy tale fantasy and real life, according to government officer Rohit Sagar

"I was a young cadet in the National Defence Academy when it released. My earliest memory of watching it in a Pune theatre on a Sunday out pass. I instantly fell in love with the movie," he said.

Kolkata-based Sagar said he related to DDLJ as a 20-year-old in 1995 and as a 45-year-old today.

"The new generation might find it a bit old-fashioned. However, a few ideas relate even to current times - to respect the one you love, to go all out to win your love without stooping low, to strike a balance between fun and commitment."

The film has projected both Western and Indian cultures in a positive way, Sagar noted.

"Even a Westernised man can display chivalry, respect for women and parents. Despite the mischief typical of the age, when the time comes, he is ready to shoulder responsibility with equal zest," he said.

Saipriya, a 17-year-old in Bengaluru, has little patience for the film and also finds the title problematic as she believes it objectifies women.

"Even at the end of the film Simran's father says 'Ja Simran. Jee le apni zindagi'. A woman doesn't need anyone else's permission to live her own life! This means she will be controlled by her father before marriage and by her husband after marriage. It's patriarchal and regressive," the young woman said.

Referring to a scene when Simran wakes up after a drunken evening in Raj's bed, Saipriya said the hero tries to trick her into believing they had sex.

"When she starts crying, he says 'Main ek Hindustani hoon aur main jaanta hoon ki ek Hindustani ladki ki izzat kya hoti hai'. Is keeping your hymen intact till marriage the greatest virtue of an Indian woman? Sex, marriage and the honour of the woman are unrelated. Also Raj clearly slut-shamed other women who have premarital sex."

Jaipur-based Zubin Mehta echoes Saipriya's sentiment about the movie's patriarchal gaze but argues that "DDLJ" is still an entertaining watch.

"It wasn't made to be a perfect romantic movie," the 30-year-old lawyer said.

Mehta added that the film put 1990s Hindi cinema on the world map in an era where the information technology sector was still in its initial stage in the country.

"DDLJ' was a stepping stone for Bollywood internationally. It was also then that we Indians peered into the lifestyle of 'gora log', which was fascinating. Their style of living, clothing and culture," he said.

What happened to Raj and Simran after the train left the station is unknown, but an ambiguous ending is what makes 'ever after' happy, Chatterjee noted.

"There is romance and hope in not knowing it. The woman has been set free and maybe she will have a brighter future. That's what Hindi cinema is about, it's about hope, not reality."

Christopher Nolan’s The Odyssey poster debuts in cinemas with exclusive teaser trailerGetty Images

Christopher Nolan’s The Odyssey poster debuts in cinemas with exclusive teaser trailerGetty Images

Deepika Padukone to get Hollywood Walk of Fame star Getty Images

Deepika Padukone to get Hollywood Walk of Fame star Getty Images  Jury Member Deepika Padukone attend the Palme D'or winner press conference Getty Images

Jury Member Deepika Padukone attend the Palme D'or winner press conference Getty Images  Deepika Padukone honoured with Hollywood star in 2026 Getty Images

Deepika Padukone honoured with Hollywood star in 2026 Getty Images  Deepika Padukone becomes Walk of Fame honouree in 2026Getty Images

Deepika Padukone becomes Walk of Fame honouree in 2026Getty Images

Charlize Theron poses with her Oscar for Best Performance by an Actress in a Leading Role during the 76th Annual Academy AwardsGetty Images

Charlize Theron poses with her Oscar for Best Performance by an Actress in a Leading Role during the 76th Annual Academy AwardsGetty Images  Charlize Theron stars in "The Cider House Rules"Getty Images

Charlize Theron stars in "The Cider House Rules"Getty Images  Charlize Theron attends the Los Angeles Premiere of Netflix's "The Old Guard 2" Getty Images

Charlize Theron attends the Los Angeles Premiere of Netflix's "The Old Guard 2" Getty Images Charlize Theron during the 2010 Soccer World Cup Final Draw Getty Images

Charlize Theron during the 2010 Soccer World Cup Final Draw Getty Images

Ramayana teaser out featuring Ranbir Kapoor and YashYoutube Screengrab

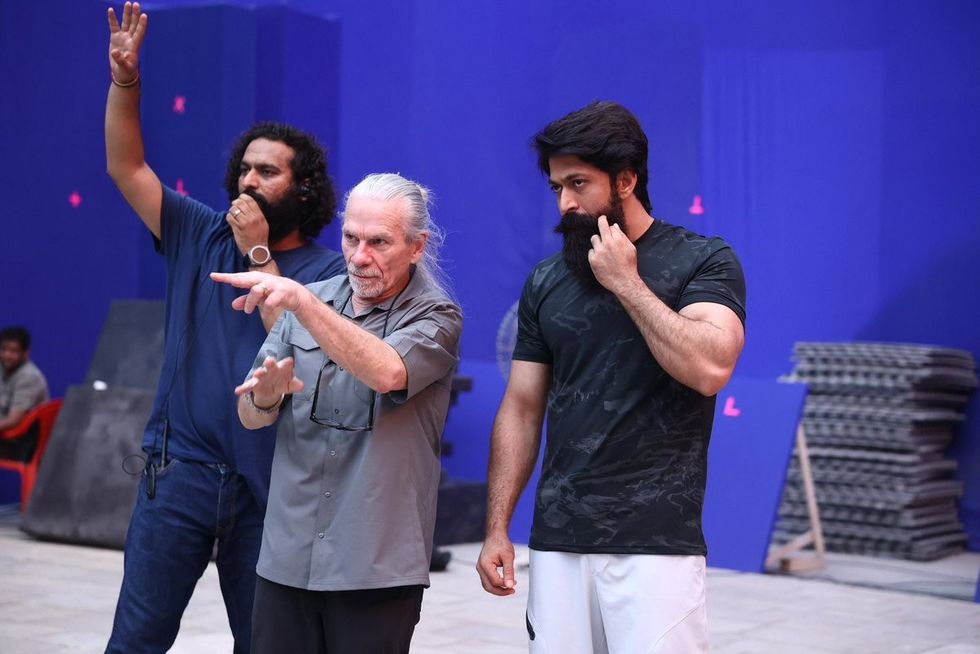

Ramayana teaser out featuring Ranbir Kapoor and YashYoutube Screengrab  Yash in discussion with stunt director Guy Norris during Ramayana shoot Twitter/@SumitkadeI

Yash in discussion with stunt director Guy Norris during Ramayana shoot Twitter/@SumitkadeI