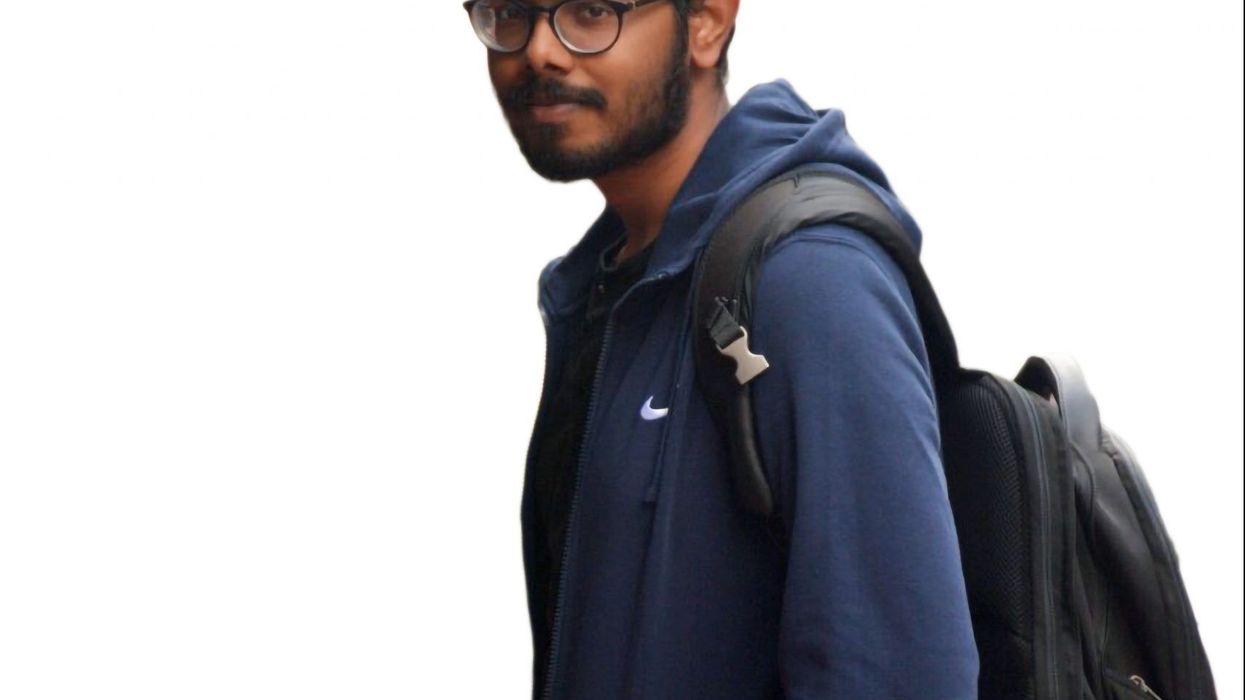

Aravind Jayan discusses his new book and love for writing

Terrific new Asian authors tackling taboo topics and, subsequently, expanding the literary horizon is illustrated perfectly by newly published novel Teen Couple Have Fun Outdoors.

The fearless debut from 27-year-old Indian writer Aravind Jayan revolves around a scandal that breaks out when an anonymously filmed sex clip of a young couple goes viral and triggers a scandalous tsunami of events. The story looking at issues like shame, desire, family loyalties, freedom and growing up in modern India, combines wit with bittersweet emotion. It has also been described as a sparkling debut, full of tenderness and mischief.

Eastern Eye caught up with the author, based in Trivandrum, Kerala, where this story is partly set, to discuss his debut novel and close connection to writing.

What connected you to creative writing?

The answer to this is sort of moronic, but I began writing seriously because I started suspecting that I was sort of good at it. If I’d been good at, say, carpentry or accounting or music, I might just as easily have done that instead.

Tell us about the story of your book?

Teen Couple is about how a middle-class family’s anxiously acquired status is threatened when the eldest son and his girlfriend (both in their early twenties) appear on a secretly-filmed porn clip posted online. The couple try their best to put the whole thing behind them, but their parents find this impossible. What follows is an intergenerational battle, which in turn becomes a news sensation that brings buried tensions to the surface and tests familial bonds. It’s narrated by the younger son who has to play the thankless role of the middleman. To me it’s about how different people and generations deal with shame, in a country where shame dictates quite a lot of things.

What inspired your debut novel?

I was always curious about these videos floating around the internet, even back in school. I mean, everyone was, and they’d always have these questions; who are these people, where are they now, how did they deal with this? So, in a sense, I wanted to try playing out that scenario and see what came out of it. Another thing was the subject of shame. When I first started this book, I was in London enrolled in a creative writing course. I was very embarrassed to be doing something so frivolous while my other friends were doing things like engineering or medicine. I think that played into the book as well.

Is any of it based on real experiences?

Not really! But the fact that the couple in the story decide to meet outdoors is not so uncommon, I think. Finding a convenient place where you can be alone with your significant other is often a problem, especially when you’re young and broke. Even more so if you’re in your hometown. That is something that I had to deal with in college as well, at least for a while, despite the fact that I had left home and was in Pune.

What kind of readers are you hoping will connect with this story?

I’m hoping the story and emotions in it are more or less universal, even if the circumstances are specific. I think it might especially resonate with people who have had to deal with stifling family atmospheres or with people who have had to put on a brave face when things are going wrong. Actually, I think a category who might enjoy it even more is siblings who’ve had to play the role of go-betweens.

What inspired the interesting title?

It is based on how porn videos are often titled. Plus, I liked the fact that it was catchy, noticeable, and inaccurate (because the couple aren’t even teenagers).

What is your own favourite part of the book?

That would be the voice of the unnamed narrator, and well, the narrator himself. I like how confused, anxious, and lost he is. He is also, to some degree, unreliable and grey. He doesn’t seem to know where family ends and self begins.

Did you learn anything new while writing the book?

I did learn that it’s hard to get everything right the first time around, so you have to throw away even more than what you actually end up keeping.

How much does the praise you have received mean to you?

It means a tremendous amount. I’m so very grateful for it. Practically speaking, even praise from an anonymous reader on Goodreads is validation in the bank. I can use that to fuel more writing.

What can we expect next from you?

I’m working on a book that’s largely about cowardice (political and otherwise), relationships and masculinity.

What books do you enjoy, and do you have a favourite?

Right now, I’m reading Chilean Poet by Alejandro Zambra, which I’m enjoying a lot. I usually read everything I can get my hands on, even if it means I end up reading quite a lot of things I don’t like. I especially enjoy reading short stories that are published in local online magazines.

In terms of writing, what is the best advice that you ever got?

That even the world’s nicest reader is an extremely impatient one. If they give you the time of the day, you ought to hurry up and get to the meat of the story. Actually, I’m not sure if this is advice I received or just something I have internalised.

What inspires you as a writer?

Reading or watching or listening to another story. I am very much inspired whenever I encounter good work.

Why should we pick up your book?

I would pick it up for the unusual and neurotic narrator. If nothing, the cover is really nice. It’ll look good on a shelf.

Teen Couple Has Fun Outdoors by Aravind Jayan is published by Serpent’s Tail at £12.99 hardback and ebook