THIS year’s annual exhibition of the Royal Society of Portrait Painting, with over 200 works on display, drives home that this is a genre where British Asian artists appear to be missing out.

There are a few, to be sure, such as Shanti Panchal, Suman Kaur and Akash Bhatt but not enough.

This is a quintessentially English and middle-class world. But perhaps British Asians will be inspired by the exhibition at the Mall Galleries in London, which this year marks the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee with a selection of her portraits, big and small. Seven of the artists were present at the exhibition’s launch to mark the seven decades of her reign.

There are so many British Asians who deserve to have their portraits painted. The Nobel Prize winner Amartya Sen had his done when he became Master of Trinity College, Cambridge, and one of Cipla boss Yusuf Hamied hangs in the Hall of his alma mater, Christ’s College, Cambridge. A portrait of the author Salman Rushdie can be seen in the National Portrait Gallery. But all these were done by non-Asian artists.

Maybe the Royal Society of Portrait Painting should make a pitch for greater diversity among its members. It is, after all, open to all. It says that “since 1891 the Society has been devoted exclusively to the art and development of portrait painting. The selection of work on display, both from its members and from the open section, make it the perfect destination for those wishing to commission a portrait. The individuals portrayed span every age and every field of human activity. Portraiture is a fascinating barometer of current trends and holds a mirror up to nature in reflecting life in contemporary Britain.”

It does that – but only up to a point.

The exhibition, it says, “celebrates the diversity of this fascinating genre. It also shows the popularity of commissioning painted portraits by institutions and individuals. All human life is celebrated here and the exhibition always includes some famous faces.”

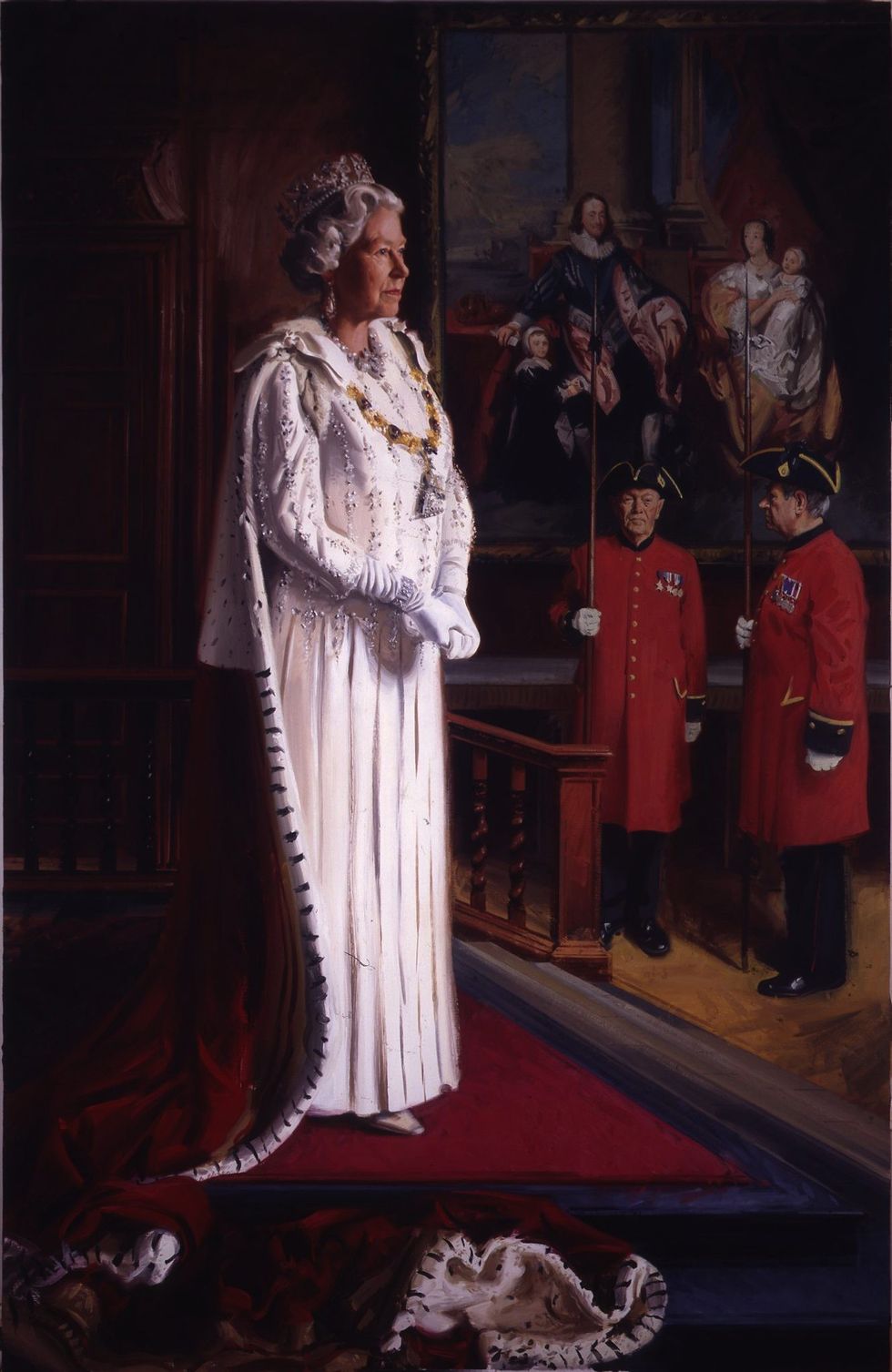

No one is more famous than the Queen, now 96, who has been painted over the years. The images are always respectful. A note explains that the Queen, the Society’s patron, “has reigned for over half of the time the Royal Society of Portrait Painters has existed. As one of the most painted figures in history, her epoch has been intertwined with portraiture, and as such, intimately connected with members of the Royal Society.

“To mark the Queen’s platinum jubilee, the Royal Society of Portrait Painters is honoured to show a curated selection of portraits of our monarch by past and present member artists, alongside our annual exhibition.

“Throughout her seven decades of service the Queen has sat innumerable times, each painting a unique vista into a remarkable life and person.

“The selected paintings exhibited at the Jubilee Exhibition 2022 represent her reign to the present day, demonstrating a wide array of artistic styles, sizes, mediums and methods.

“Each artist who receives such an illustrious commission confronts diverse challenges in painting the monarch. Primarily, they are presented with a figure of state, embodied in tradition – an emblematic position that transcends the everyday to take a place in history. Conversely, and most salient to a portraitist, each painting looks for the intimate expression of a human being.”

Painting the Queen must be a daunting experience but she appears to put the artists at ease.

Miriam Escofet revealed that her “portrait was commissioned in 2019, the year I won the BP Portrait Award with a portrait of my mother. So in my mind both works are somehow linked. I wanted to paint a portrait of the Queen that felt intimate and aimed to express her human qualities, rather than a more traditional and regal representation of her.”

When she met the Queen, “I was struck by several qualities: firstly by her radiance, but also her keenness, her down-to-earthness, her humour and her warmth. The first sitting took place at Windsor Castle in July of 2019, the second sitting in February of 2020, just a week before the country went into lockdown.”

Benjamin Sullivan, who won the BP Portrait Award in 2017, said of his work which was started in February 2018 and finished in 2020: “Set in the white drawing room at Windsor Castle, the work seeks to capture the Queen relaxed and comfortable. The background is gently simplified so as not to detract from the portrait itself.”

Sue Ryder said of her work commissioned in 1997 by the Royal Automobile Club: “I painted Her Majesty over four sittings in the magnificent Green Drawing Room at Buckingham Palace, the Queen kindly often extending her sitting time. I was also able to paint on after the sittings had ended for as long as I liked. Not taking photographs of this was very important for me as I work from what I see and from memory.”

Clearly, sought-after portrait painters can make a good living.

Andrew Festing, who “has painted some 750 portraits in the last 30 years”, said of his regal representation: “When you paint someone like the Queen you have to change the way you do things, so I did a sketch of the Queen and then transferred that onto the larger canvas, since you can’t really turn up at Buckingham Palace with a seven foot canvas. The two pensioners who also appear in the portrait, RSM Daley & RSM Loat, came to my studio in London to sit for me for studies.”

Inaugurating the exhibition last Wednesday (4), the broadcaster Gyles Brandreth told the artists present: “You are civilised people in an uncivilised world.”

He also said that portraits ensured that those who were painted were “not forgotten” and continued to be remembered by family and friends.

The Royal Society of Portrait Painters annual exhibition in honour of The Queen’s Platinum Jubilee runs until Saturday (14). Admission £5, free for under 25s and Friends of Mall Galleries.