By Amit Roy

ANYONE who has followed the history of the hastily executed partition of India In 1947 will be familiar with its terrible consequences. It is generally estimated that a million people died in the communal carnage that took place as Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs caught on the wrong side of newly drawn borders sought to flee to safety.

The bulk of the killings took place in Punjab on the western side of India as West Pakistan was created almost overnight. But there was slaughter in the eastern side of the country, too, as West Bengal remained in India, while East Bengal became East Pakistan, and subsequently today's Bangladesh after the bloody war of secession in 1971.

What is new is that some of the survivors, who were children at the time of partition, moved in time to Britain to become part of the South Asian diaspora. It is their stories that Kavita Puri has re-counted, first in her BBC Radio 4 series, and now in her book, Partition Voices: Untold British Stories (Bloomsbury; £20). Mingled in with the horror stories are accounts of Hindu, Muslim and Sikh neighbours giving shelter to those threatened by mob violence at great risk to themselves.

One of the most moving accounts in Kavita's book is that of her own father, Ravi Dan Puri, who was born in Lahore and was 12 at the time of partition. As Kavita scatters his ashes into the Ganges in the city of Haridwar in the Himalayas, she reflects that her father, like so many others, had kept silent for 70 years about what he had experienced at partition.

"Born in Lahore, Pakistan, an adult life lived in England, he now rests somewhere along the most sacred and blessed river in India," his daughter writes.

"My father had been cremated near his home in Kent in his favourite suit and shoes, along with fresh rose petals, camphor, ghee and tuts/ leaves, which we had sprinkled on his body during the final rites."

She describes the moment when his ashes are scattered in the river - as so many Indians in the UK have done with their loved ones: "The priest began his Sanskrit prayers. Following his instructions, we threw marigolds and rose petals on the ashes, while the priest sprinkled holy Ganges water. When the time came, my sister and I took the plate and ashes, which were now almost covered by flowers, to the river's edge, where the water's lapped our bare feet, as we held our father for the last time.”

As the priest offered the final prayer, "holding each side of the plate, my sister and I gently tipped it towards the river, allowing my father's ashes to slowly descend slowly into the waters, the waters which had carried his forefather's ashes. We watched as his remains swirled in the Ganges, drifting away from us."

The partition had taken him from Lahore via Kent to Haridwar.

The point that was made at Kavita's very well attended book launch at Daunt Books in Marylebone last Wednesday (3) is that these stories have a wider significance. The survivors are now in the twilight of their lives or have already passed away. As Kavita has made clear, the time window to catch their stories before it is too late is now closing.

To be sure, they are part of the history of Indians, Pakistanis and Bangladeshis in Britain, but they also constitute an important aspect of modern "British history.”

As such, it is right that the history of partition which has shocked so many in Britain should be included in the school syllabus. There are those who balk at the idea and fear teaching colonial history will become a Brit-bashing exercise. But perhaps a way can be found of dealing with the painful events of partition without apportioning blame - as Kavita has done.

What is fresh about her book is that she has included not only the tales of Indians and Pakistanis but also British people who now live quintessentially English lives in, say, rural parts of the UK but who once bore witness to partition.

For example, there is an evocative photograph of Pamela Dowley Wise as a teenager on her bike in Calcutta, the city where she was born during the Bengal famine. She was pushed off her bike in 1946 during the "Quit India" movement She is now 91 and runs riding stables in Surrey, but has returned to India often and has "always retained her love for the country.”

Given the history of partition, it is encouraging how the relationship between Indians and Pakistanis in Britain has been relatively trouble free over the years. Cricket matches between India and Pakistan - for example, during this summer's world cup - have been talked up as almost war by other means.

British journalists who have turned up in the expectation of discord have been disappointed to find matches played in sporting spirit with Indian and Pakistani fans sitting alongside each other, cheering on their respective sides, but also sharing their snacks and good-humoured banter.

"I think the relationships between the different South Asian communities in Britain are certainly different than on the subcontinent and not as polarised in the same way," Kavita has suggested to Eastern Eye by way of explanation.

But she qualified her remark by adding there were "complex" underlying issues: "In the early years, people who came to Britain from India and Pakistan worked side-by-side in the factories and foundries and fought together for equal pay and against racism. In Britain everyone was lumped together as 'Asian'; religious differences so pronounced on the Indian subcontinent were far less important in post-war Britain.”

But she added: "Divisions appeared from the 1980s, and the communities today are quite separate - inter-marriage, for example, is rare - but they are not hostile, by any means." Kavita's Partition Voices takes its place alongside other valuable books on partition such as Khushwant Singh's Train to Pakistan and Urvashi Butalia's The Other Side of Silence.

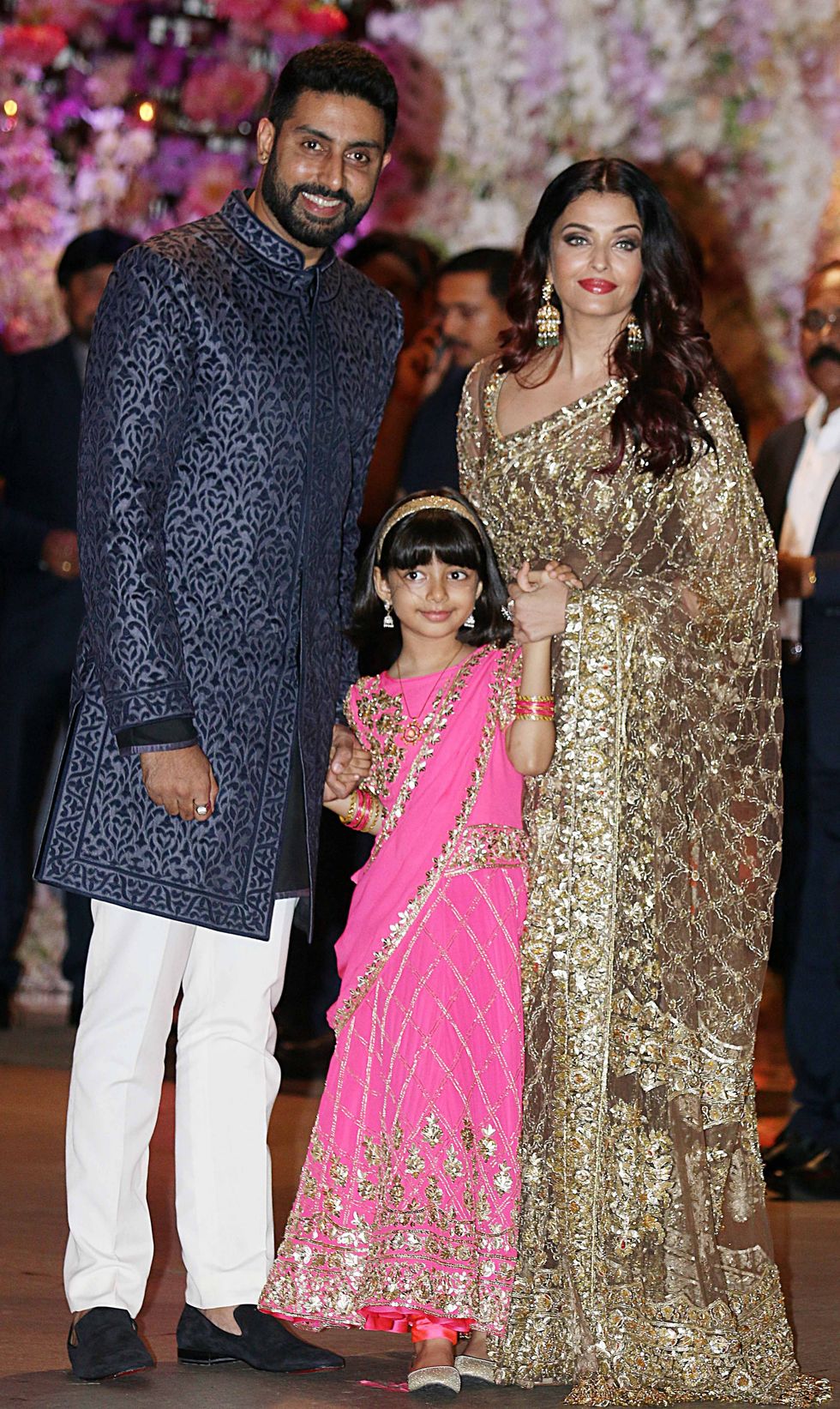

Aaradhya Bachchan has no access to social media or a personal phoneGetty Images

Aaradhya Bachchan has no access to social media or a personal phoneGetty Images  Abhishek Bachchan calls Aishwarya a devoted mother and partnerGetty Images

Abhishek Bachchan calls Aishwarya a devoted mother and partnerGetty Images Aaradhya is now taller than Aishwarya says Abhishek in candid interviewGetty Images

Aaradhya is now taller than Aishwarya says Abhishek in candid interviewGetty Images Aishwarya Rai often seen with daughter Aaradhya at public eventsGetty Images

Aishwarya Rai often seen with daughter Aaradhya at public eventsGetty Images

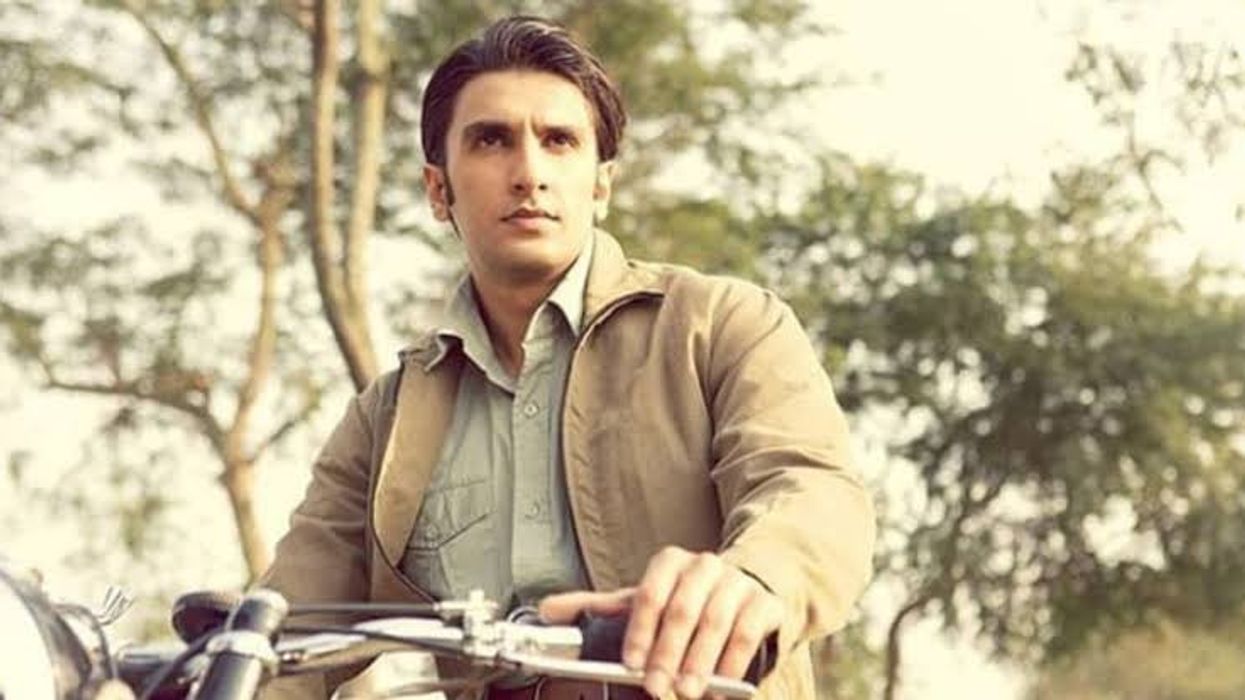

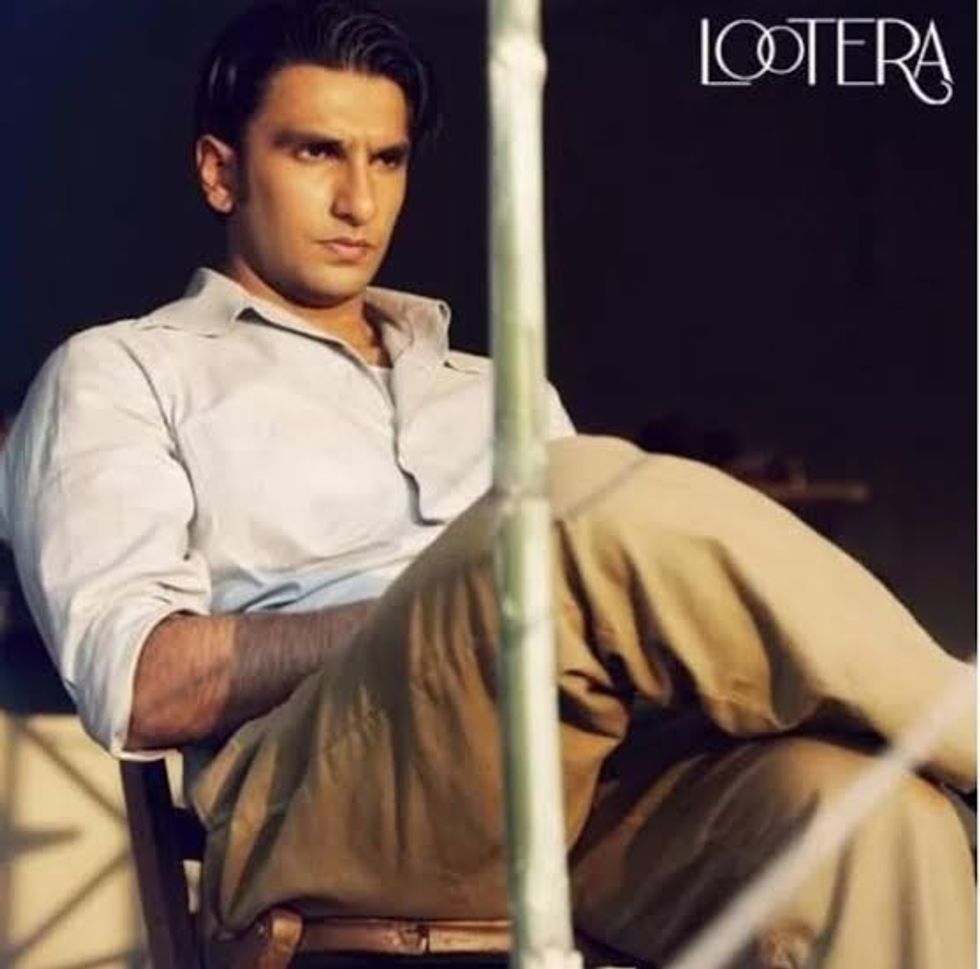

Lootera released in 2013 and marked a stylistic shift for Ranveer Singh Prime Video

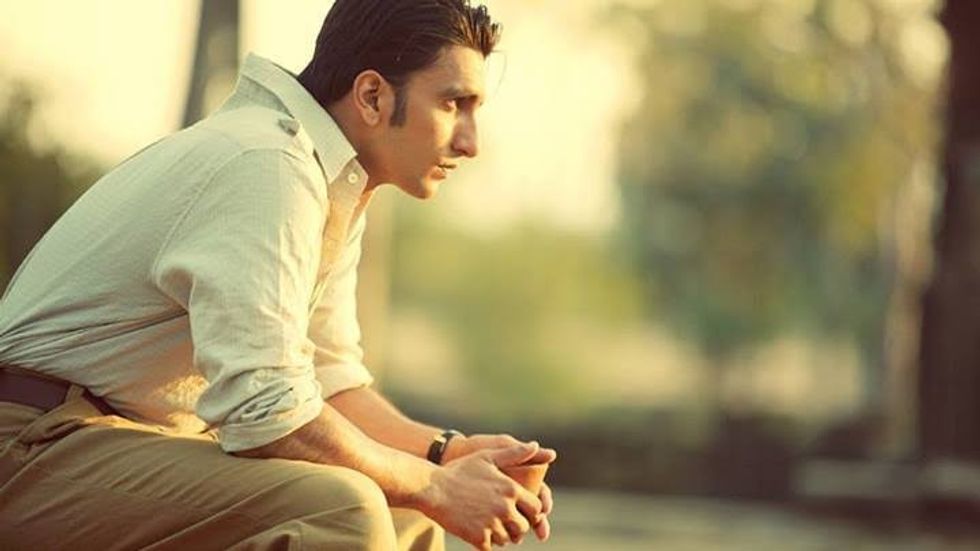

Lootera released in 2013 and marked a stylistic shift for Ranveer Singh Prime Video  Ranveer Singh’s role as Varun showed he could command the screen without saying much

Ranveer Singh’s role as Varun showed he could command the screen without saying much The period romance Lootera became a turning point in Ranveer Singh’s career

The period romance Lootera became a turning point in Ranveer Singh’s career Ranveer Singh’s performance in Lootera was praised for its emotional restraint

Ranveer Singh’s performance in Lootera was praised for its emotional restraint Ranveer Singh and Sonakshi Sinha starred in the romantic drama set in 1950s BengalYoutube/Altt Balaji Motion Pictures

Ranveer Singh and Sonakshi Sinha starred in the romantic drama set in 1950s BengalYoutube/Altt Balaji Motion Pictures  Lootera’s legacy has grown over the years despite its modest box office runYoutube/Altt Balaji Motion Pictures

Lootera’s legacy has grown over the years despite its modest box office runYoutube/Altt Balaji Motion Pictures

AR Rahman confirms collaboration with Hans Zimmer on InstagramInstagram/

AR Rahman confirms collaboration with Hans Zimmer on InstagramInstagram/

Ozzy Osbourne to perform one final time in BirminghamGetty Images

Ozzy Osbourne to perform one final time in BirminghamGetty Images  Ozzy Osbourne and Black Sabbath reunite in Birmingham for farewell concert after two decades Getty Images

Ozzy Osbourne and Black Sabbath reunite in Birmingham for farewell concert after two decades Getty Images

Priyanka Chopra calls herself nascent in Hollywood as 'Heads of State' streams on Prime VideoGetty Images

Priyanka Chopra calls herself nascent in Hollywood as 'Heads of State' streams on Prime VideoGetty Images  Priyanka Chopra wants to build her English film portfolio after Bollywood successGetty Images

Priyanka Chopra wants to build her English film portfolio after Bollywood successGetty Images  Ilya Naishuller, Priyanka Chopra and John Cena attend the special screening for "Head of State" Getty Images

Ilya Naishuller, Priyanka Chopra and John Cena attend the special screening for "Head of State" Getty Images