by Amit Roy

IT SEEMS like the British government has no option but to try to prevent president Emmanuel Macron of France from becoming US president Donald Trump’s new best friend.

It has been announced that Trump will come to Britain on a “working visit” on Friday, July 13 – one assumes he is not too superstitious. This is a little like inviting a guest, but asking him to enter the house through the tradesman’s entrance.

Trump’s latest comments about the crime levels in London have, as expected, caused widespread offence. Speaking to the National Rifle Association (NRA) convention in Dallas last Friday (4), he said: “They don’t have guns. They have knives and instead there’s blood all over the floors of this hospital. They say it’s as bad as a military war zone hospital ... knives, knives, knives. London hasn’t been used to that. They’re getting used to that. It’s pretty tough.”

Bhupinder Iffat Rizvi, whose 20-year-old daughter, Sabina, was shot dead in Kent in 2003 after being caught up in a dispute about a car, said: “I found his speech very, very offensive. Is he really suggesting we should legalise guns?

“He needs to look at his own hometowns where young people are standing up against gun ownership. They don’t want to be put in a situation where they are being shot at in schools.”

That said, one should not take comfort from the much higher murder rates in America.

A trauma surgeon, Martin Griffiths, at the Royal London Hospital, said recently: “Some of my military colleagues have described their practice here as being similar to being at (Helmand province’s former camp) Bastion. We routinely have children under our care – 13, 14, 15 year-olds are daily occurrences, knife and gun wounds.”

Over the last weekend, boys aged 13 and 15 were injured in gun attacks, and a 17-year-old, Rhyhiem Ainsworth Barton, killed.

Labour MP David Lammy reacted: “Enough. Enough. My heart goes out to families grieving children and teenagers. So many shattered lives, families and communities.”

Last year, London had a total of 116 murders, including at least 80 stabbing and 10 gunshot victims. This year, the figure is up to 60 already.

Part of the solution is better policing. But why is so much of knife and gun crime “black on black”? As the Windrush affair has shown, black people still feel relegated to the margins of society.

Shashi Tharoor

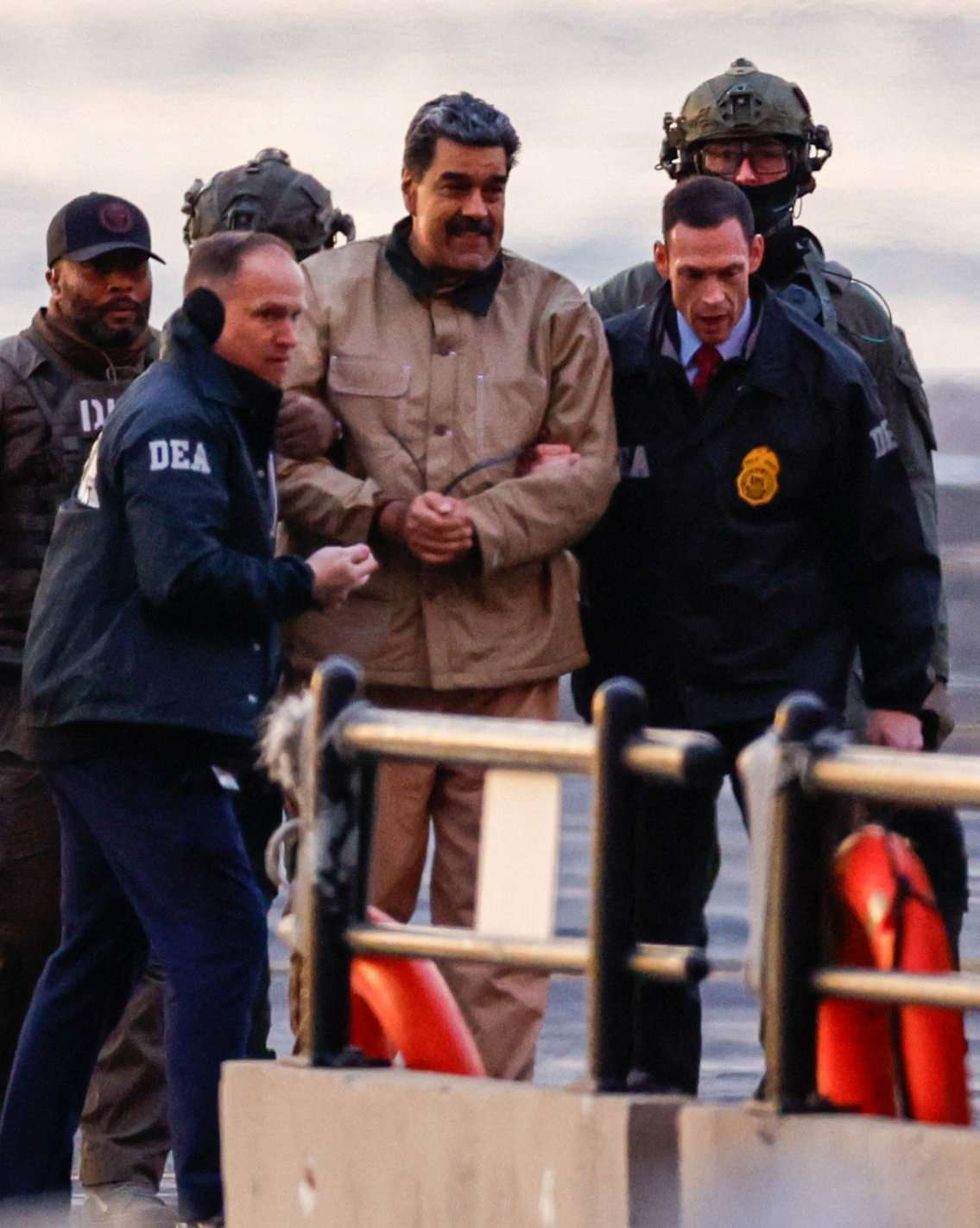

Shashi Tharoor Nicolás Maduro arriving at the Down town Manhattan Heliport.

Nicolás Maduro arriving at the Down town Manhattan Heliport.