THE Taj Mahal figures both in The Great Mughals: Art, Architecture and Opulence exhibition at the V&A and also in Rajiv Joseph’s play, Guards at the Taj, at the innovative Orange Tree Theatre in Richmond.

The treatment could not be more different. At the V&A, the Taj is an object of unparalleled beauty, with stunning drone footage of the marble mausoleum. There are also examples of the intricate marble work for which the Taj is famous. The exhibition catalogue has fine drawings of the cenotaphs of Shah Jahan and Mumtaz Mahal inside the burial chamber in the Taj.

In a chapter, Portable monuments: The reproduction of Mughal architecture, Divia Patel, curator, south Asia in the Asian Department at the V&A, has written: “A particularly fine example is the cenotaph of Shah Jahan in which a delicate hand and a pronounced attention to detail is evident. Along the top edge is a finely inscribed title ‘The tomb of his Majesty whose Seat is in paradise – of Saheb Kerayn the Second – The Emperor Shah Jehaun – Sanctified be his dwelling’.”

She says: “Together with the images of the cenotaphs of Shah Jahan and Mumtaz Mahal these illustrations demonstrate the artists’ careful delineation of the floral designs and Koranic inscriptions on the tombs. The rendering of each flower, leaf, stem and scroll accurately copies the original even on such small-scale drawings. Close observation indicates that the artists have attempted to replicate the natural stratification of the coloured stone that constitutes an individual petal within a flower, as well as the exterior range of hues of the overall scheme.”

In Guards at the Taj, Shah Jahan’s sparkling white marble creation has an unseen presence, but nevertheless casts a dark shadow across the lives of the play’s two protagonists. They are Humayun and Babur, who have been friends since they were boys, but are now members of the Imperial Guard charged with guarding the Taj. They are played by Maanuv Thiara and Usaamah Ibraheem Hussain, respectively. The play is directed by Adam Karim on a minimalist stage.

There must be a reason why the playwright, Rajiv Joseph, who is American, has called his characters, Humayun and Babur. The Mughal dynasty was founded by Babur (1483-1530), who was succeeded by his son, Humayun (1508- 1556). He was followed by the great Akbar (1542-1605), and Jahangir (1569-1627), before the throne passed to Shah Jahan (1592-1666). History books tell us the Taj Mahal, commissioned by Shah Jahan in memory of his wife, Mumtaz Mahal, took 20,000 men 20 years to build.

Legend has it that Shah Jahan wanted to build an exact replica of the Taj, but in black marble on the other side of the Jamuna river. But he died before the project could get under way and was buried next to Mumtaz. That is said to explain why his grave is the only thing that is asymmetrical in the whole structure.

Many myths attach to the Taj. One is that Shah Jahan had the chief architect’s thumb cut off so that he would not be able to build another Taj. But in Guards at the Taj, Joseph goes further and has Humayun and Babur chop off the hands of all 20,000 craftsmen who worked on the project. The stage is stained with blood as are their clothes.

Credit is given in the programme to a company called “Pigs Might Fly”, Orange Tree’s “Theatrical Blood Supplier”. There is no evidence that Shah Jahan was guilty of any such cruelty, but the legends have come down the centuries through the power of oral story telling.

Joseph begins his play in 1648 when the Taj is very nearly built. But the emperor has forbidden anyone to look at his creation until the finishing touches are completed. But using the exchanges between Humayun and Babur, Joseph wants to examine deeper issues, such as freedom of speech and what happens in a society subjected to authoritarian rule.

From the start, Humayun is portrayed as someone who is rigid in his thinking and comfortable only when blindly following orders. Babur is much more rebellious and anxious to explore the world around him. In the very first scene, he turns up late, tries to get dressed quickly, holds his sword in the wrong hand and clearly irritates Humayun.

When he tries to chat about the bird sounds in the jungle, Humayun admonishes him, “Would you be quiet!”, and adds, “Imperial Guards of the Great Walled City of Agra, Sworn to the Eternal Dominion of His Most Supreme Benevolence Emperor Shah Jahan ... Do Not Speak.”

He points out, “Among the Sacred Oaths of the Mughal Imperial Guard is to Never Speak,” and that, “In silence, we are vigilant.”

Babur is told: “The tiniest of infractions will see us both gone, quick-stuffed to the lowliest gullies of Agra.”

There is a sliding scale for sedition: “Punishment for Mild Sedition: 40 lashes with a whip and a shaved head. And Medium Sedition carries a sentence of blinding. Extreme Sedition: Being sewn into the hide of a water buffalo and left in the sun for seven days. And in the case of Treason: Death by elephant. All of which is to say, Babur, shut up. Imperial Guards are Not To Speak!”

“You won’t tell on me,” pleads Babur.

Humayun is not reassuring: “Well, I won’t lie.”

“Come on! We’re brothers, you and me,” says Babur. Humayun is dismissive: “We’re not brothers, we’re just friends.” Humayun is worried he will lose his job, but apparently his father is well connected, according to Babur: “And who is your father? Only simply the highest of high command in the All-On-High Imperial Guard.”

Humayun is obviously scared of his father, which is significant because the time will come when he will be called upon to sever Babur’s hands as a condition of allowing his friend to live. But in the end Humayun appears to go further and executes his friend for questioning the authority of the emperor. But that is yet to come.

Babur wants to see the Taj before the emperor has given his permission.

“They say it’s white,” offers Humayun.

“Yeah, but just white?” wonders Babur. “Is it skinny? Is it fat? I mean, what shape will it be? All we know are those protective walls that have hidden it these past 16 years.”

He goes on: “It’s crazy! 16 years in the making! Since we were kids, they’ve been building this! And yet we have no idea what it will look like!”

Humayun is not moved: “His Most Supreme Emperor Shah Jahan decreed that no one shall see it until it is fully completed.” Humayun does not like it when Babur says he dreams of being allocated guard duty in the emperor’s harem where he would be “surrounded by naked women!” He tells Babur that “it’s not some depraved house of sluts!”, “it’s not some hotbed of wanton lust!” and, with a straight face, “it’s a government department, like any other office. It’s where the emperor does his most confidential work”. In the end, Babur, sickened by the blood, protests, “20,000 people don’t have hands,” and rejects Humayun’s defence, “We carried out our duties efficiently.”

And Babur pays the ultimate prices for raging against the emperor. Disturbing and gripping, but not a play to take your children.

Guards at the Taj is playing at the Orange Tree Theatre in Richmond until Saturday (16)

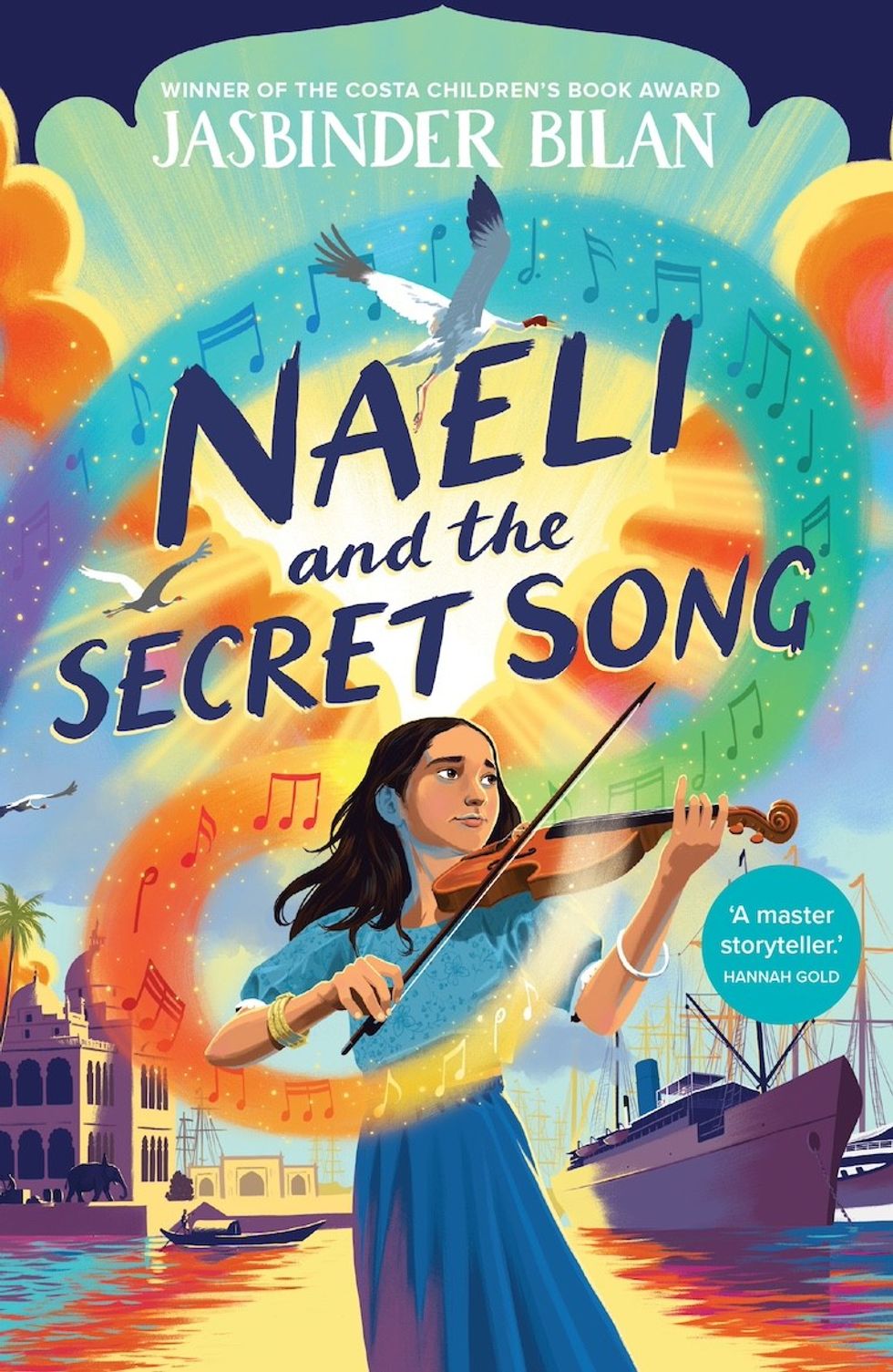

Naeli and the secret song

Naeli and the secret song

Jamie Lloyd’s Evita with Rachel Zegler set for Broadway after London triumphInstagram/

Jamie Lloyd’s Evita with Rachel Zegler set for Broadway after London triumphInstagram/

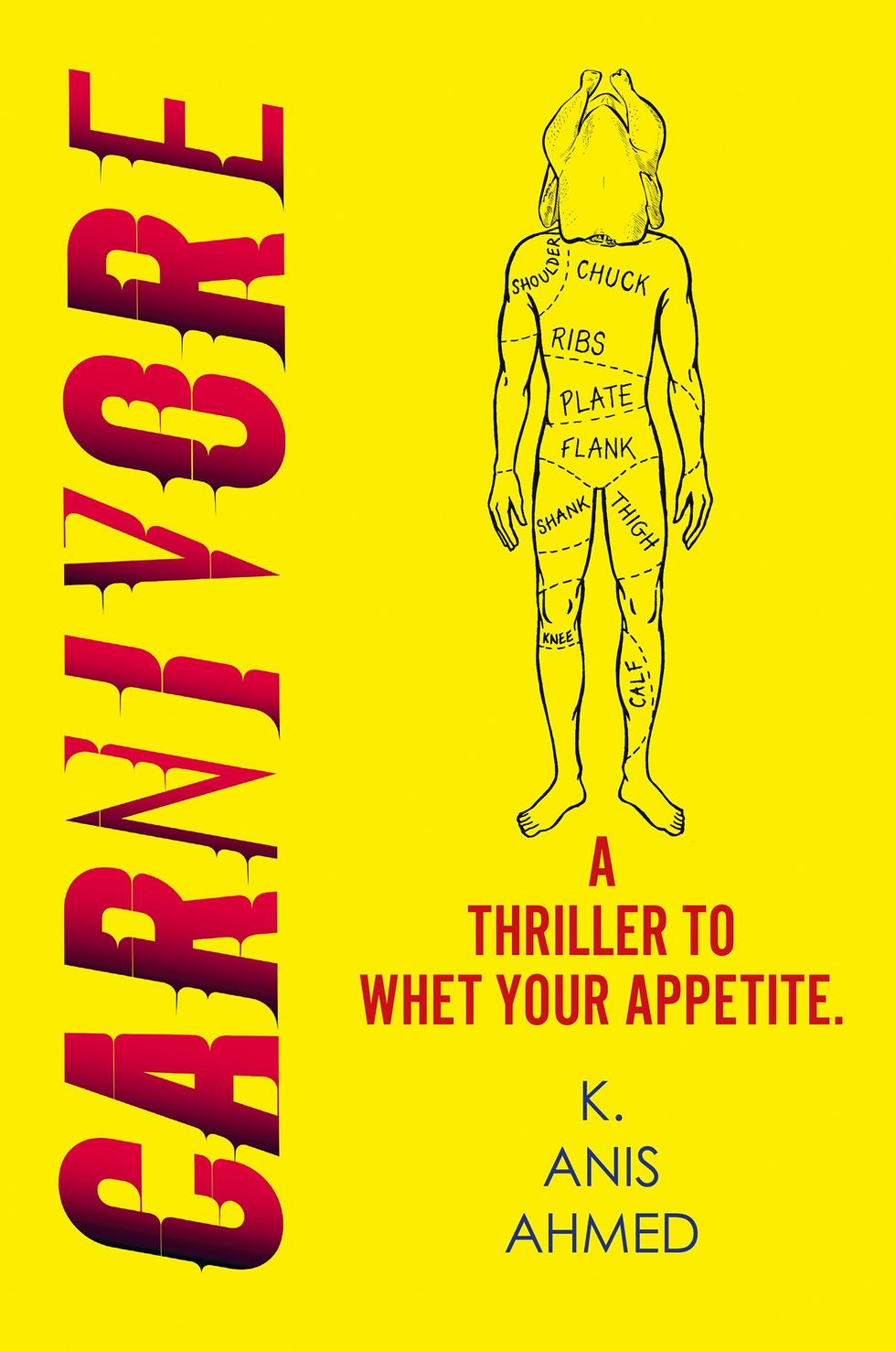

A compelling premise, layered and unpredictable charactersAMG

A compelling premise, layered and unpredictable charactersAMG Anyone who enjoys a gripping story with a diverse cast and unexpected twistsHarperFiction

Anyone who enjoys a gripping story with a diverse cast and unexpected twistsHarperFiction

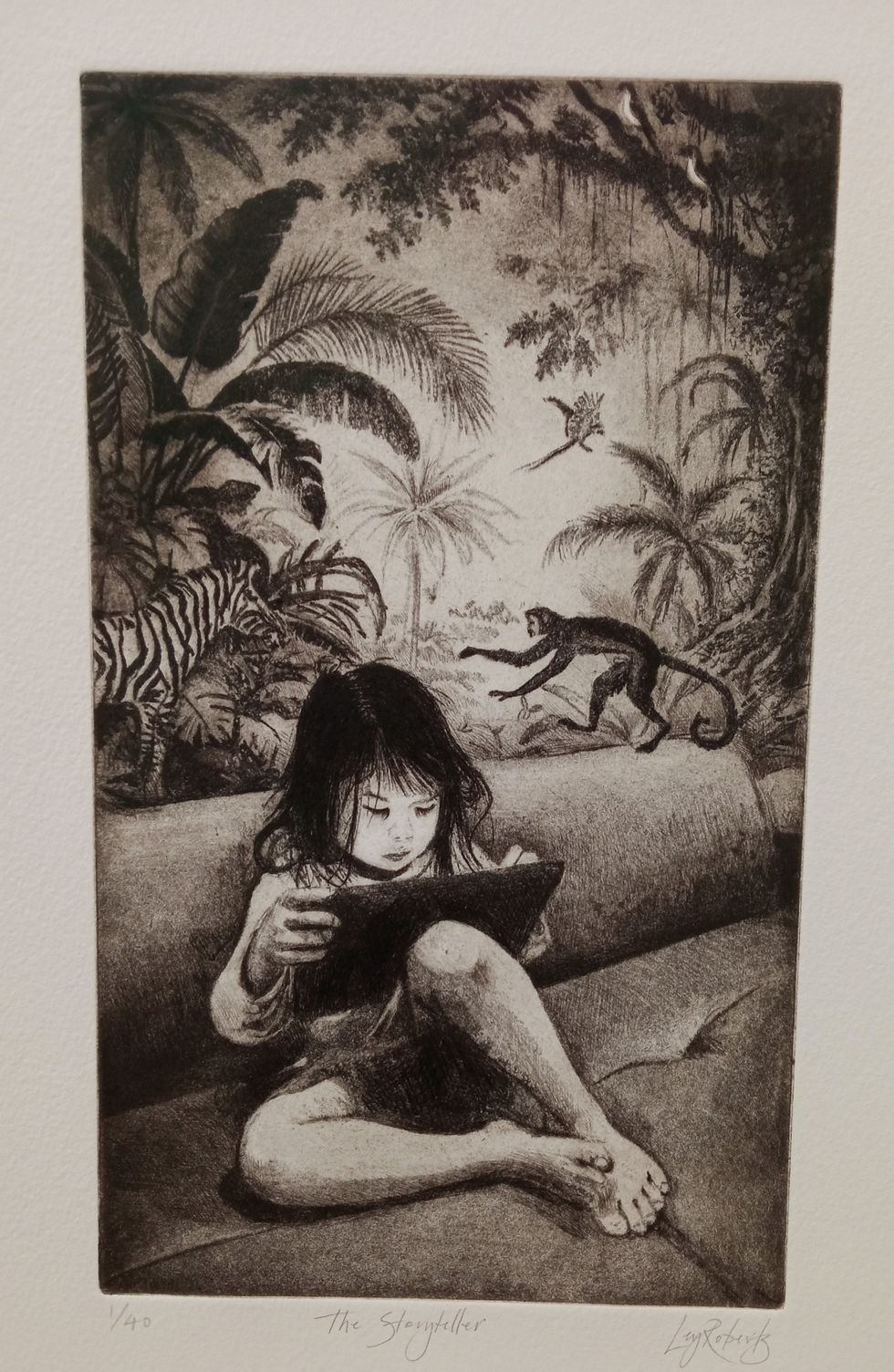

The Story Teller by Ley Roberts

The Story Teller by Ley Roberts Summer Exhibition coordinator Farshid Moussavi, with Royal Academy director of exhibitions Andrea Tarsia in the background

Summer Exhibition coordinator Farshid Moussavi, with Royal Academy director of exhibitions Andrea Tarsia in the background An installation by Ryan Gander

An installation by Ryan Gander A sectional model of DY Patil University Centre of Excellence, Mumbai, by Spencer de Grey

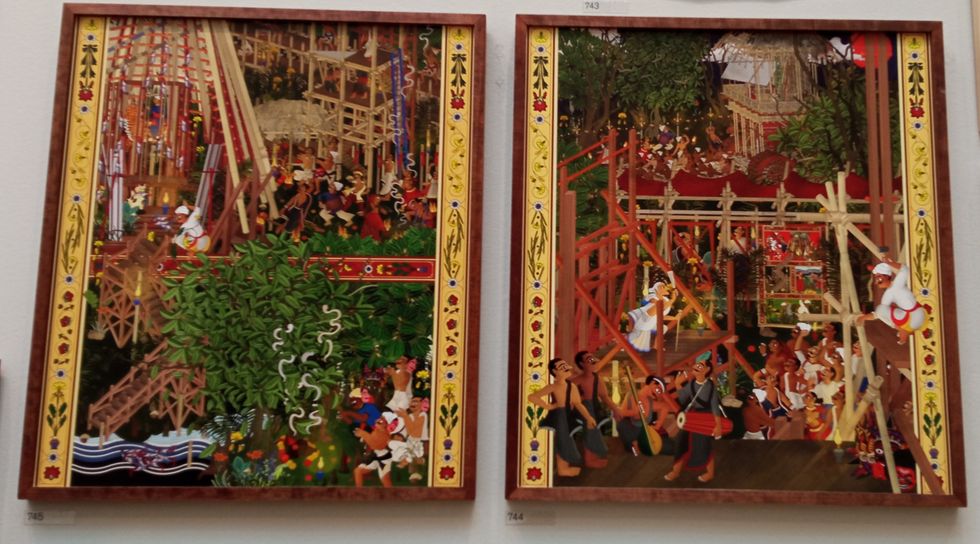

A sectional model of DY Patil University Centre of Excellence, Mumbai, by Spencer de Grey Rituals and Identity and Theatre of Resistance by Arinjoy Sen

Rituals and Identity and Theatre of Resistance by Arinjoy Sen