WHEN author Shelina Janmohamed couldn’t find any relevant books on the British empire for her two young daughters, she decided to write her own book, titled Story of Now – Let’s Talk About the British Empire.

Her two daughters, aged nine and five at the time, were keen to learn more about British history after watching the statue of slave trader Edward Colston being torn down by anti-racism campaigners in Bristol, in 2020.

“My daughters are huge history buffs so I wanted to give them something to read that might help them to understand a bit more about the British empire,” Janmohamed told Eastern Eye.

“To my absolute shock, I couldn’t find anything for them to read at that age. I couldn’t believe that the biggest empire ever - there wasn’t something that was written about for children.

“I thought, well, if nothing exists, I’m going to have to write it myself.”

Janmohamed is an established writer whose books include the bestselling Love in

a Headscarf, a memoir about growing up as a British Muslim woman; and Generation M: Young Muslims Changing the World, an exploration of a group of global Muslims who believe that faith and modernity go hand in hand.

Her first children’s book, The Extraordinary Life of Serena Williams, told the story of the tennis champion whose experiences of life-threatening illnesses, sports injuries, sexism and racism in the sport did not stop her from her exemplary achievements.

Despite Janmohamed’s background as a writer, she said she felt daunted to tackle the subject of the British empire.

“I actually say in the book that when Edward Colston fell, I had never heard of him. Probably surprising to hear that somebody writing about the British empire had never heard of him, but it was something I learned,” she said. “The empire was a big thing. It went on for 400 years across 25 per cent of the world. It was quite hard work to get it all into a little book.

“I haven’t written the whole history of the empire. What I’ve tried to do is give a framework of key things that happened and tried very hard to make sure that as many regions of the world that were part of the British Empire get a little spotlight.

“People can then go away and explore the parts that are relevant to them and they find interesting.”

The British empire is not currently a part of either primary or secondary school history curriculum.

“It’s the biggest empire ever, so purely from a historic perspective, it’s affected the whole world,” said Janmohamed. “The amount of books that kids read about the Greeks, the Romans, the Aztecs and they’re all really important, but to think the empire that’s lasted the longest, spread the widest, has had the biggest impact and is about where we live today, isn’t something that’s taught, I find it completely baffling.” Two years ago, a YouGov poll found that 32 per cent of people in Britain are actively proud of the nation’s colonial history. However, some argue it’s not something to be proud of as the empire was built through vicious military conquests, enslavement, massacres, famines and partitions to create profit.

In the subcontinent, some estimates suggest up to one million people alone lost their lives in the aftermath of the Partition of India and Pakistan in 1947.

Janmohamed said a more nuanced approach was needed when teaching children about the complexities of the British empire. “It’s interesting that we try to address the question of the British empire as a question of morality – as though it says something about who we are.

“But when we talk about the Romans or the Greeks or the Egyptians, we don’t approach the question of empire with them as one of morality,” she said.

“Empire happened. That’s just an incontrovertible fact. Whether we agree about the details of what happened, the impact and what our perspective should be - that’s all up for debate. But for children, that culture war is not really something that I think should affect their lives.”

Janmohamed said she was more interested in how she could connect British colonialism to children’s lives today; hence the first part of the title of the book – The Story of Now. “I talked to children about migration, that the British empire is responsible for the biggest migrations in human history and some of them are very connected to children,” she said.

“I tell them the story of the home children - from Britain, who were sent away to the colonies, for all sorts of reasons, some of them being to build the empire, some of them because, frankly, the people in Britain didn’t want the poor, ‘scallywags’ on the streets, they wanted to just deport them out of here. When those children got to the colonies, they were rejected. They were, as migrants, told that they shouldn’t talk about it.

“I speak about how children used to work in the industrial revolution and how the stories that those children told changed the labour laws and it means children today can go to school and don’t have to work.” Janmohamed added: “While we might want to discuss the morality, it’s a red herring, because for children, it’s happened. We need to focus on what can we get from learning about it that will help them to understand who they are and the kind of world we hope they will build for us.”

She is also a prominent social commentator on Islam and current affairs. She has written for publications such as the Times, the Guardian, the Telegraph and the Independent and appeared on the BBC and ITV. She also has her own national podcast.

Janmohamed said the UK still remains a country where, often, people of colour are looked at as foreigners, despite having generations of family members who have lived in the country or have a connection to the country through colonialism.

“At the beginning of the book, I tell my story of how I came to be in Britain,” she said. “My family have been part of Britain for more than 200 years.

“My family is from Gujarat and was there when the East India Company turned up in 1608 and took over India. At the end of the 19th century, they travelled to Tanzania and then, in the 1960s, my parents came to London because they were overseas subjects of the British empire.

“I was born here. The British empire and my story are very much the same story, they’re intertwined. The power of not just my own story, but the power of children finding their own stories is that you understand how your life has been shaped by the British empire.”

The 49-year-old said learning about the empire will help with social cohesion as different communities learn about their own shared history.

“I came to this book as somebody who’s really interested in identity. Who are we now? What makes me who I am? How do I find my place in history?” she said.

“This is why the book is called Story of Now. It says in the strapline, this is not a history book. This isn’t about something that’s past. This is about finding who you are. Because when you know your story and you listen to somebody else’s story, that’s how we create a really great society. That’s how you create social cohesion because you understand who you are and what shapes you and also understand who somebody else is, and then you can have a dialogue.”

One of the ways of finding out who you are, Janmohamed said, is to learn your history from your loved ones. “I’m a firm believer that one of the greatest treasures we have are the oral histories from the people of our families,” she said.

“One of the greatest skills we can teach our children is how to get those first-hand accounts from parents and grandparents. I tell children the oral history of your family is probably the most exciting part of history you will ever find because it’s not in books and it’s what shaped who you are.

“That’s what I want kids to take away from the book, to understand who they are in the context of the world around them.”

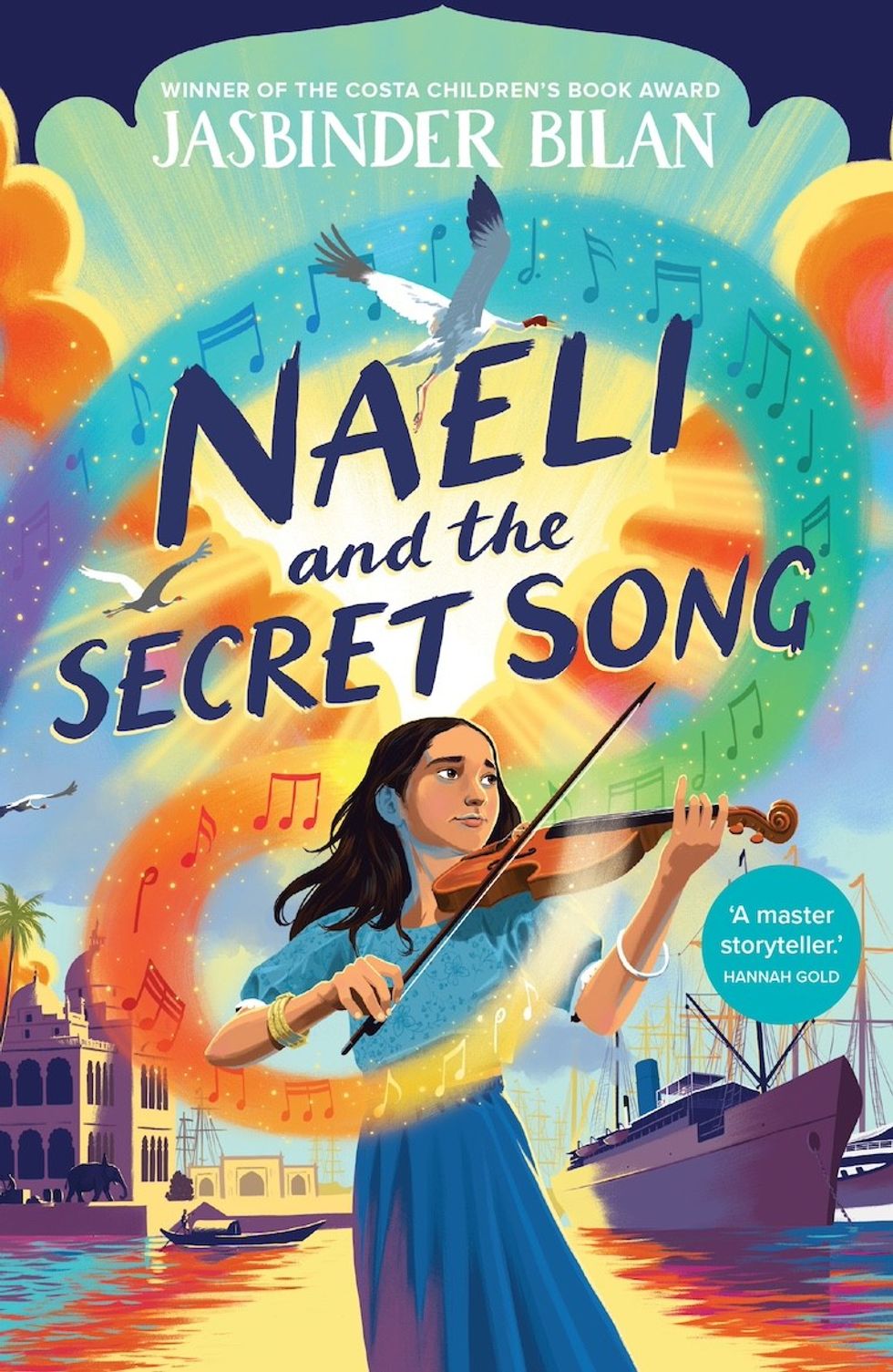

Naeli and the secret song

Naeli and the secret song

Jamie Lloyd’s Evita with Rachel Zegler set for Broadway after London triumphInstagram/

Jamie Lloyd’s Evita with Rachel Zegler set for Broadway after London triumphInstagram/

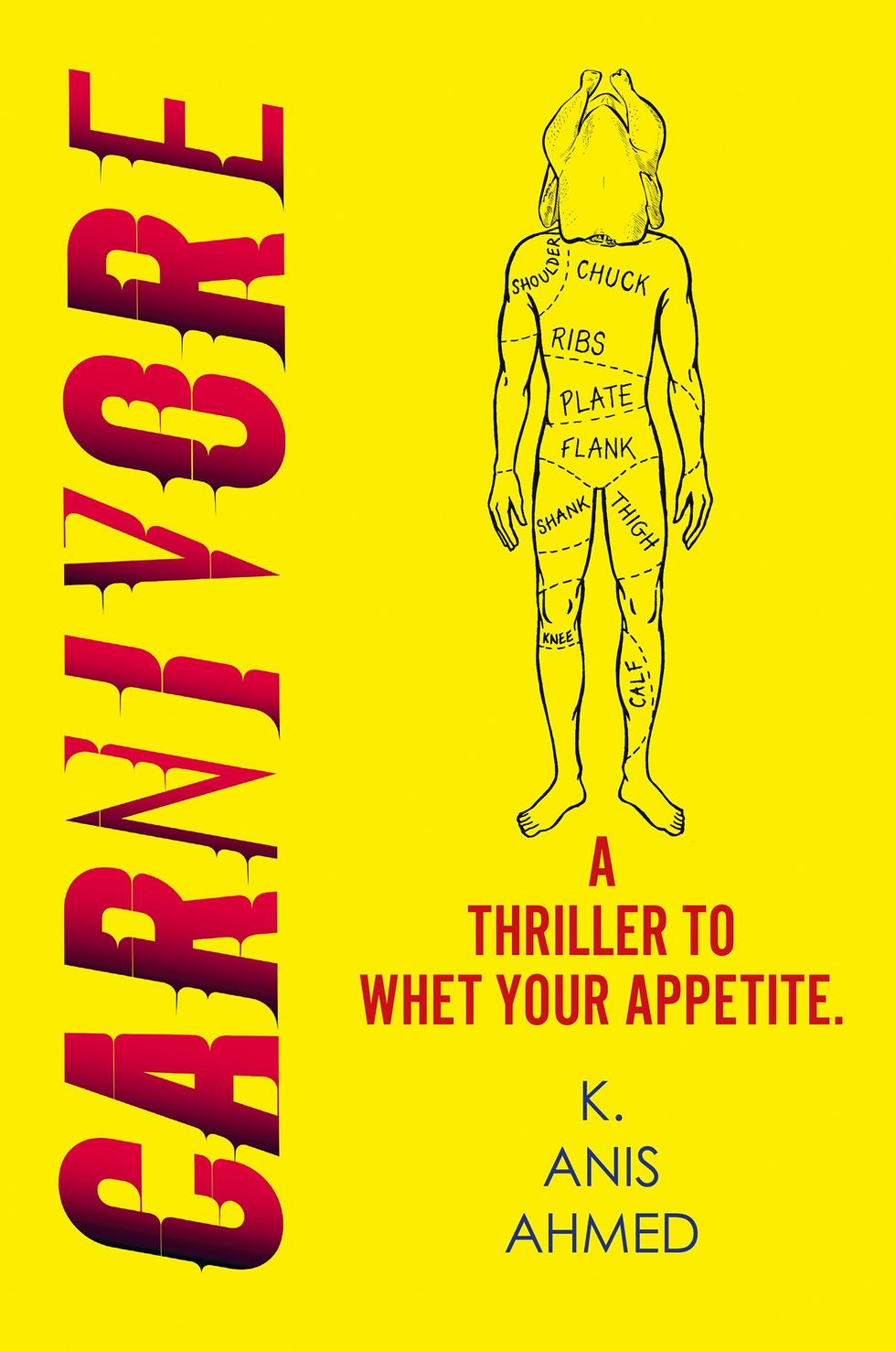

A compelling premise, layered and unpredictable charactersAMG

A compelling premise, layered and unpredictable charactersAMG Anyone who enjoys a gripping story with a diverse cast and unexpected twistsHarperFiction

Anyone who enjoys a gripping story with a diverse cast and unexpected twistsHarperFiction

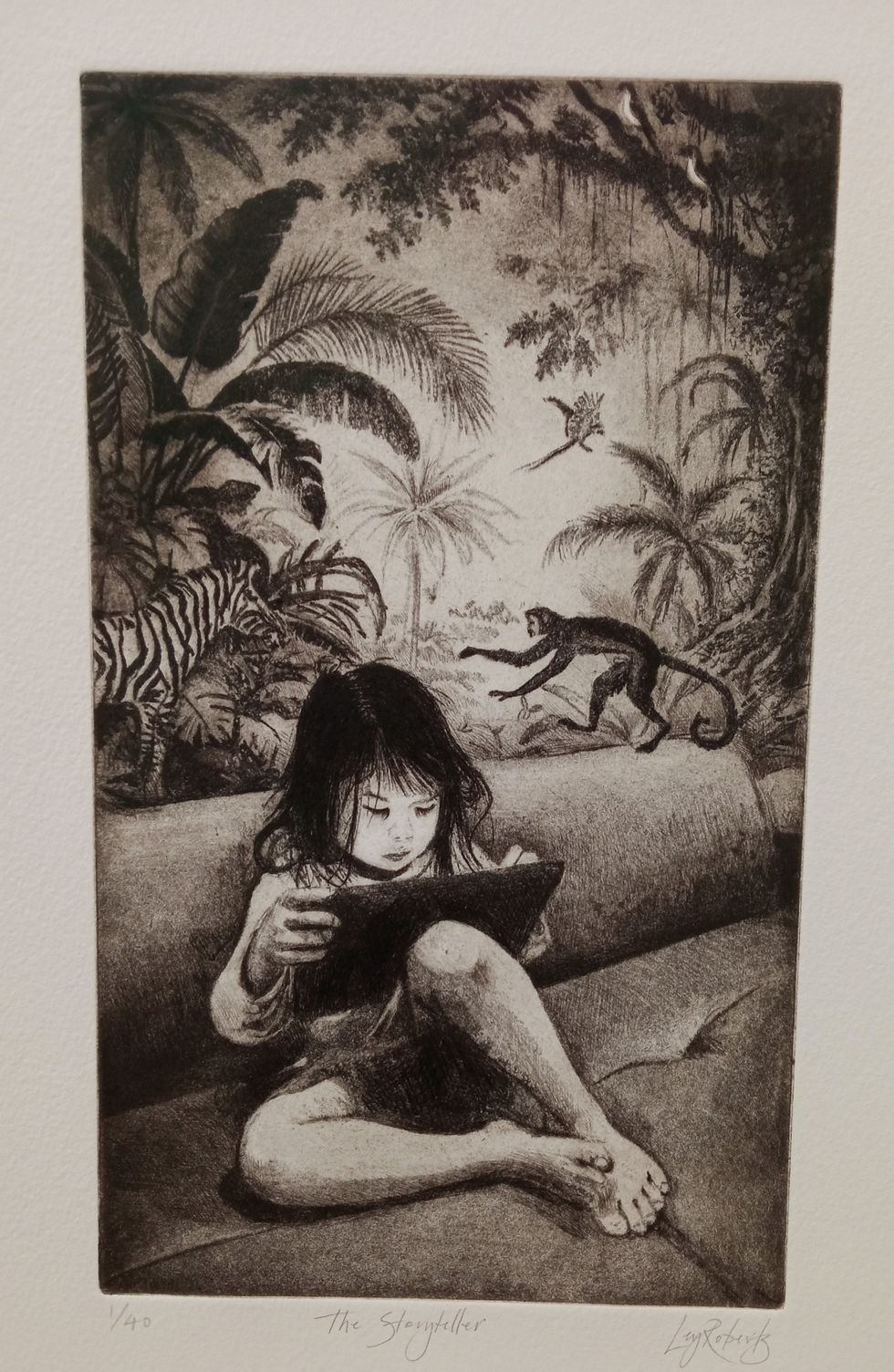

The Story Teller by Ley Roberts

The Story Teller by Ley Roberts Summer Exhibition coordinator Farshid Moussavi, with Royal Academy director of exhibitions Andrea Tarsia in the background

Summer Exhibition coordinator Farshid Moussavi, with Royal Academy director of exhibitions Andrea Tarsia in the background An installation by Ryan Gander

An installation by Ryan Gander A sectional model of DY Patil University Centre of Excellence, Mumbai, by Spencer de Grey

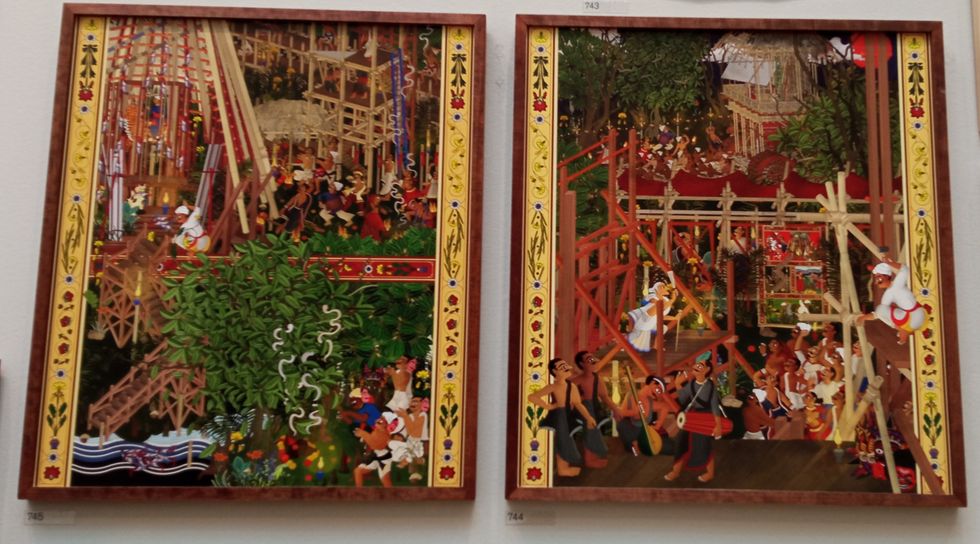

A sectional model of DY Patil University Centre of Excellence, Mumbai, by Spencer de Grey Rituals and Identity and Theatre of Resistance by Arinjoy Sen

Rituals and Identity and Theatre of Resistance by Arinjoy Sen

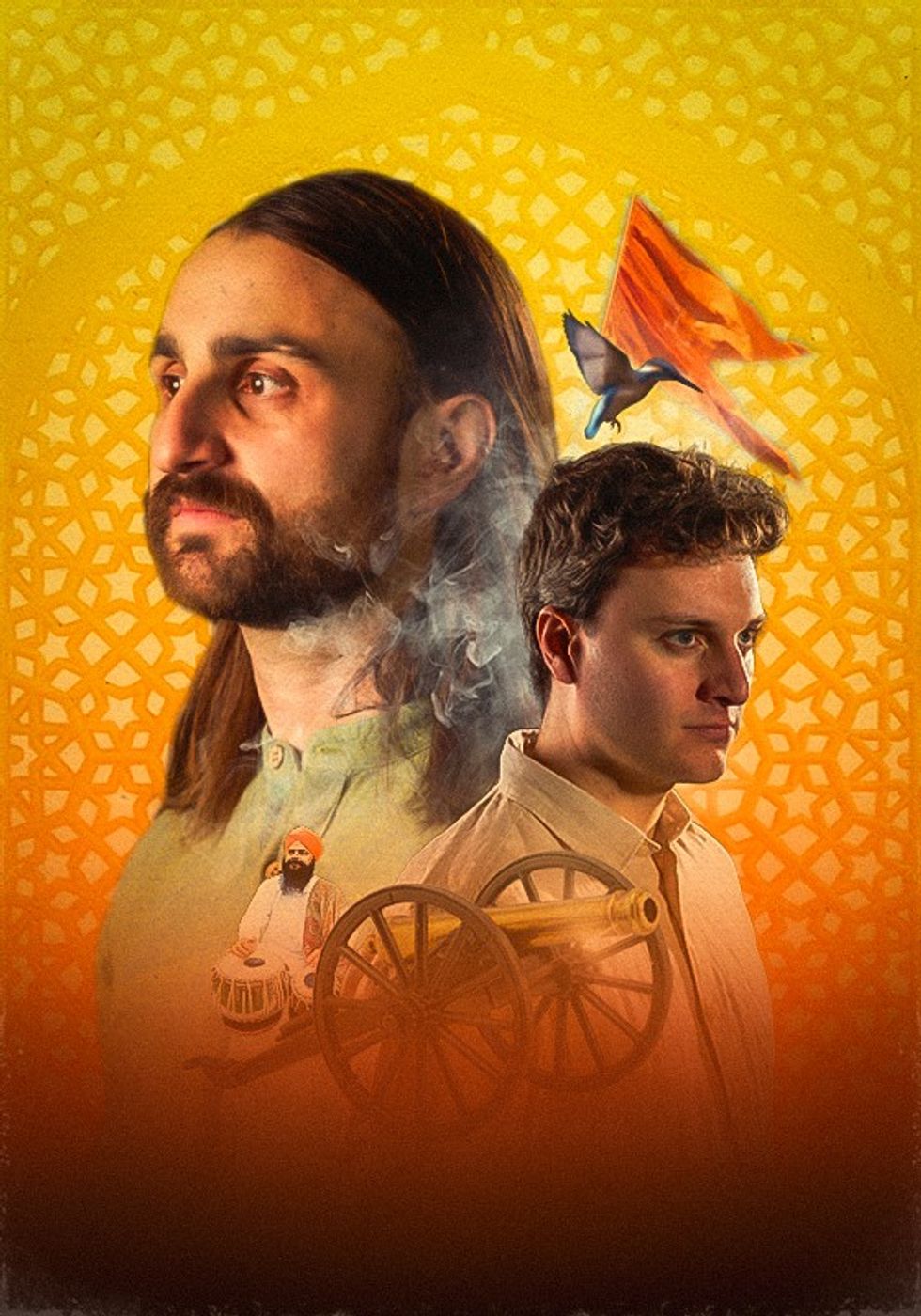

An explosive new play that fuses biting satire, history and heartfelt storytellingPleasance

An explosive new play that fuses biting satire, history and heartfelt storytellingPleasance