TENTS made by skilled workers in Rajasthan have been shown at this year’s Chelsea Flower Show.

They have been imported from India by the Raj Tent Club, a company co-founded in the 1990s by Nicola Marks.

One of the company’s employees, Davina, told Eastern Eye: “Nicky adores India. She is everlastingly fascinated, just loves India. So, she spends a lot of time there. She goes there every year, sometimes, twice a year.”

She added: “What could be better than sitting in a lovely garden in a beautiful tent, with a gin and tonic, or having lunch or supper with friends?”

The company has a note on how it was established: “During the early to mid-1990s, our late designer Clarissa Mitchell, who was living in Jodhpur, started to make decorative tents in partnership with the maharajah, using traditional designs with a modern touch.

“In doing so, they revived the tent industry in Rajasthan which had almost disappeared, and helped to preserve many ancient skills such as block printing, embroidery, mirror work and tassel making that are used in the making of the tents.

“In 1996, Clarissa met Nicola Marks, our current managing director, and together they launched Raj Tent Club in London the following year.

“It was the first company to introduce decorative tents to the UK event industry. Initially, the company only sold the tents, but we quickly realised that our tents were ideal for corporate events, weddings and other private celebrations and so the rental division of our company was started.

“We now provide beautiful tent installations for over 200 events per year. We work all over the UK, and over the years, we have provided tents for events in France, Italy, Portugal, Ireland, Switzerland, Bahrain and Qatar.”

It said: “All our tents can be lined with beautiful block print linings and there is a wide choice of lighting, rugs, furniture, accessories and props to go inside them. For outdoor tents, we can provide sunshades, parasols and garden furniture, ideal for summer events.

“It is our aim as a company to support traditional handicrafts and to provide ethically made products of high quality from around the world.”

The company said its tents, which come in various sizes, have been “inspired by the Mughal traditions of India”.

There is also information about the history of tents, both under the Mughals and later as part of British rule.

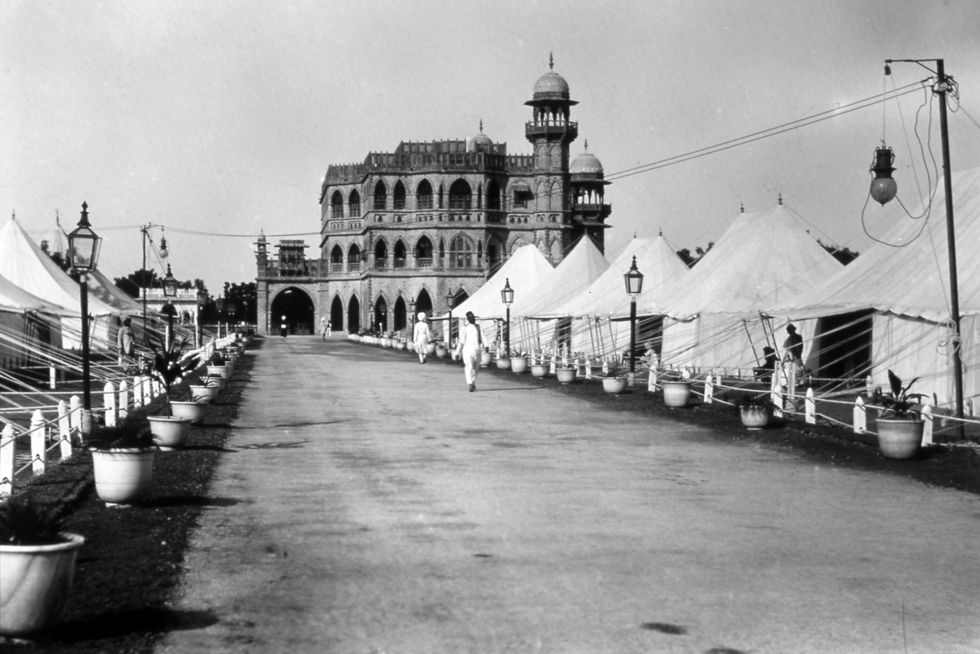

“India, and particularly the desert state of Rajasthan, have always had a special nomadic tent culture. In the era of the Mughal emperors, whole tented cities were often erected for royal weddings, special celebrations, durbars and hunting expeditions into the Thar Desert.

“In 1903, the most lavish and extensive example of these tented camps was set up in Delhi by Lord Curzon for the Coronation Durbar of King Edward VII, the purpose of which was to confirm the king as the Emperor of India, and also to announce the moving of the capital from Calcutta to New Delhi.

“It accommodated an astonishing 12,983 people. The viceregal camp was superbly equipped with every comfort and luxury and contained exquisitely presented camps from all the different princely states and neighbouring kingdoms displaying the finest examples of local craftsmanship and materials.

“However, by the mid-20th century, the tradition of these magnificent tented camps had sadly died out, and the skills required to make them were becoming a distant memory.

“During the mid-1990s our late designer Clarissa Mitchell was living in Jodhpur working on a project for the current maharajah.

“Inspired by photographs of the tented camps she had seen in the museum at Mehrangarh Fort, she suggested to the maharajah that they should revive the art of decorative tent making. His Highness agreed and Clarissa’s first commission was for 80 Shikar tents pitched along the lake at the camel fair in Pushkar. Further tented camps followed at Jaisalmer and Nagaur, followed by commissions all over India.

“Hence the tent industry in Jodhpur was restarted and is now a thriving one, providing much needed employment for the city.”

Some of the fabrics have been done in collaboration with the V&A.

In 2016, when Eastern Eye launched its Arts, Culture & Theatre Awards (ACTAs), the V&A won an ACTA for its landmark exhibition, ‘The Fabric of India’. It was co-curated by Divia Patel, now a member of the ACTA judging panel.

Priyanka Chopra calls herself nascent in Hollywood as 'Heads of State' streams on Prime VideoGetty Images

Priyanka Chopra calls herself nascent in Hollywood as 'Heads of State' streams on Prime VideoGetty Images  Priyanka Chopra wants to build her English film portfolio after Bollywood successGetty Images

Priyanka Chopra wants to build her English film portfolio after Bollywood successGetty Images  Ilya Naishuller, Priyanka Chopra and John Cena attend the special screening for "Head of State" Getty Images

Ilya Naishuller, Priyanka Chopra and John Cena attend the special screening for "Head of State" Getty Images

Arijit Singh performing Instagram/

Arijit Singh performing Instagram/ Arijit Singh clicked during a performance Getty Images

Arijit Singh clicked during a performance Getty Images

Liam Gallagher accepts Oasis' award for 'Best Album of 30 Years' Getty Images

Liam Gallagher accepts Oasis' award for 'Best Album of 30 Years' Getty Images  Liam Gallagher plays to a sell out crowd at the Universal AmphitheatreGetty Images

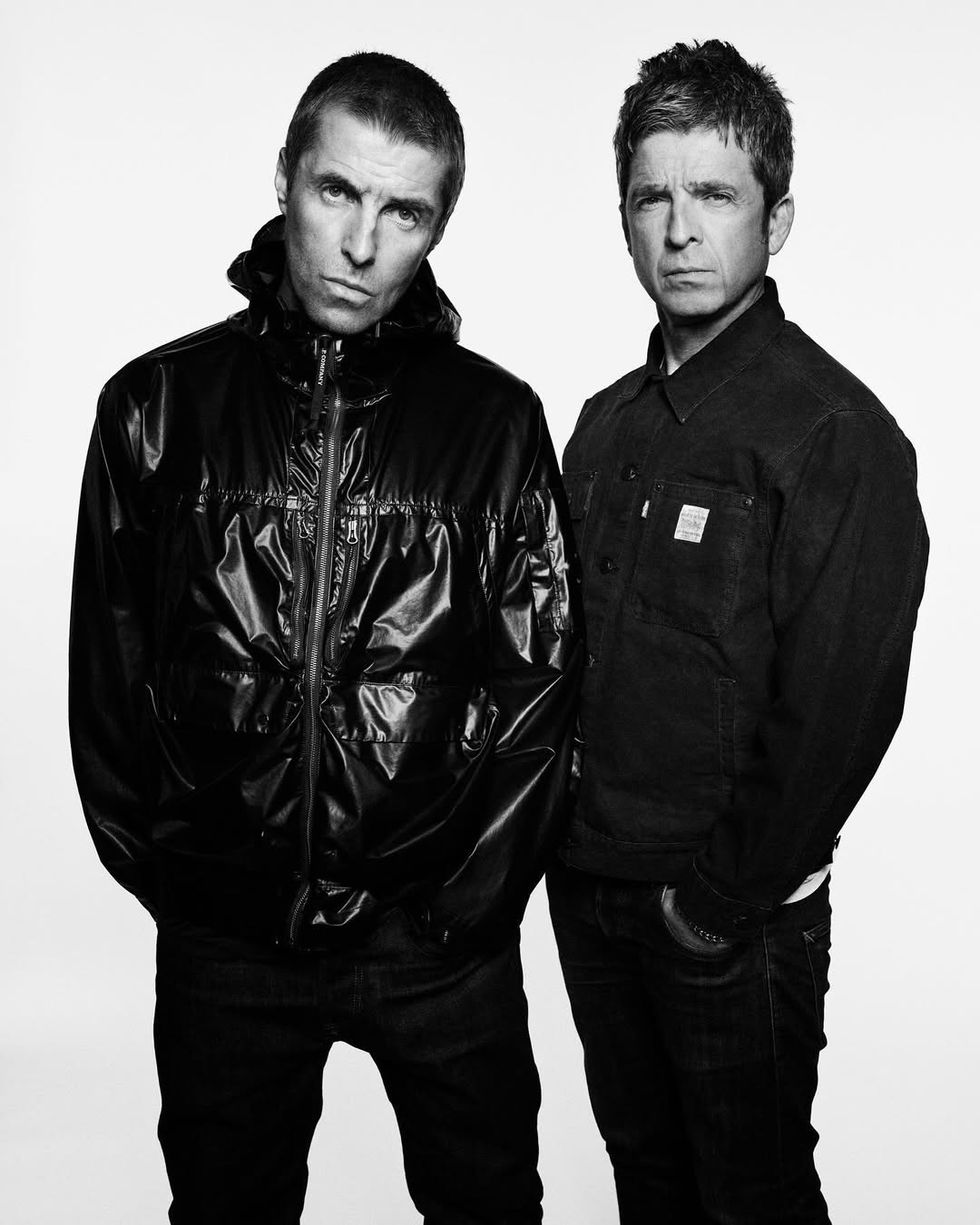

Liam Gallagher plays to a sell out crowd at the Universal AmphitheatreGetty Images Liam and Noel Gallagher perform together in Cardiff for the first time since 2009 Instagram/oasis

Liam and Noel Gallagher perform together in Cardiff for the first time since 2009 Instagram/oasis