It is two months since Shazia underwent a so-called virginity test during a rape examination at a Karachi hospital, but the Pakistani teenager is still visibly traumatised.

She winces as she describes how the doctor carried out the "two-finger test" (TFT), in which a doctor inserts fingers into the vagina, ostensibly to determine if a woman or girl is sexually active.

"She put her finger and then something else inside me. I screamed loudly as it hurt a lot and told her to stop, but she continued and said angrily that I will just have to bear it," said Shazia, whose real name the Thomson Reuters Foundation has withheld.

Women's rights campaigners in Pakistan have long fought for virginity testing to be banned, arguing it is degrading, and that a woman's sexual history has no bearing on whether she has suffered rape.

The World Health Organization said in a 2018 report the tests had "no scientific merit" and were painful and humiliating, and called for a global ban.

In Pakistan, a series of legal rulings has raised hopes of an end to the practice, most recently in January when a court in the most populous province declared the test illegal, upholding a challenge by a group of campaigners.

It is over a decade since Pakistan's Supreme Court ruled that a rape complaint cannot be dismissed on the basis of a virginity test.

But women working in the Pakistani judicial system said the tests were still widely used, blaming a lack of resources as well as deep-seated misconceptions about sexual violence.

Summaiya Syed Tariq is a police surgeon who has been working with assault survivors in Pakistan's Sindh province since 1999, carrying out rape examinations, conducting autopsies and presenting evidence in court.

She stopped carrying out two-finger tests in 2006 after becoming aware of the damage they can do, and has been working to raise awareness ever since.

But with just 11 female medical workers available to carry out rape exams in the whole of Karachi - Pakistan's biggest city with more than 16 million inhabitants - Tariq said the two-finger test was often regarded as a "quick fix".

"The issue of virginity, or how 'habitual' a woman may be to the 'act', should never be a consideration for the examiners," she said in comments on WhatsApp.

"Commercial sex workers can be raped too. The charge of rape, per se, should be enough to carry out examination and investigation and past sexual history should not be taken into consideration."

LOW CONVICTION RATE

Many human rights organisations have condemned virginity testing as inhumane and unethical, and it is banned in many countries.

India's government issued guidelines in 2014 saying the test "had no bearing on a case of sexual violence", though women's rights campaigners have said it is still being used.

In Afghanistan, a study last year found that forced gynaecological examinations were being conducted in contravention of a 2018 law that requires either the consent of the patient or a court order.

Pakistan's president announced a ban in December as part of a raft of measures to strengthen the country's laws on sexual violence following a public outcry over the gang rape of a woman who was stranded after her car ran out of fuel.

But those measures will soon expire unless parliament votes them into law.

Mirza Shahzad Akbar, an advisor to Prime Minister Imran Khan, said the measures would be presented to parliament after elections to the upper house, due to be held on March 3.

Pakistan's minister for human rights, Shireen Mazari, tweeted her support for a ban last month, calling the practice "demeaning and absurd".

She was responding to a Lahore high court ruling that virginity tests should not be carried out. The judge called it a "humiliating practice which is used to cast suspicion on the victim, as opposed to focusing on the accused".

A similar challenge is now being heard in the high court of Karachi, capital of Sindh province, where Tariq works.

Last year she selected 100 rape cases in Sindh at random to see whether two-finger tests had been conducted. She found 86 of the victims had, like Shazia, been subjected to the test.

Shazia said the medic who carried out her test appeared angry and in a hurry.

The man accused of raping her is in custody, but she and her family have had to leave the neighbourhood where they lived due to the stigma that surrounds rape in Pakistan.

She is receiving help through lawyer Asiya Munir, who works with campaign group War Against Rape (WAR), and believes the two-finger test is a factor in Pakistan's low conviction rate for rape.

Less than 3 per cent of sexual assault or rape cases result in a conviction in Pakistan, according to the Karachi-based group.

"It is very traumatising for a person already in a state of shock," said Munir, criticising what she called the "almost accusatory tone" of many rape investigations.

"I am certain there has to be a more dignified and less humiliating way of finding the truth."

Actress Bella Thorne and Charlie Puth attend the Y100's Jingle Ball 2016Getty Images

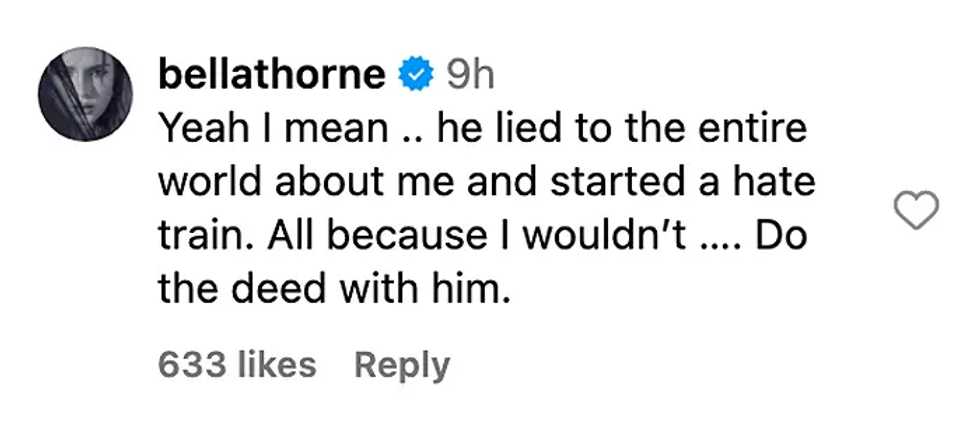

Actress Bella Thorne and Charlie Puth attend the Y100's Jingle Ball 2016Getty Images  Bella Thorne's commentInstagram Screengrab

Bella Thorne's commentInstagram Screengrab  Charlie Puth performs onstage at an interactive global eConcert liveGetty Images

Charlie Puth performs onstage at an interactive global eConcert liveGetty Images  Bella Thorne and Mark Emms attend a red carpet for the movie "Priscilla"Getty Images

Bella Thorne and Mark Emms attend a red carpet for the movie "Priscilla"Getty Images Charlie Puth and Brooke Sansone attend the 10th Breakthrough Prize CeremonyGetty Images

Charlie Puth and Brooke Sansone attend the 10th Breakthrough Prize CeremonyGetty Images