by Amit Roy

AS THE nation marks the centenary of the end of the First World War, historian Dr Kusoom Vadgama has expressed concern that the Indian soldiers are being split up according to religion – Muslims, Sikhs and Hindus.

She has a point when she asserts: “They did not fight as Muslims or Sikhs or Hindus. They fought as Indian soldiers.”

It may be politically expedient to pick out, say, Muslim achievement as a way of countering allegations of Islamaphobia in contemporary Britain, but that is to twist history. For

example, Khudadad Khan is now projected as the “first Muslim to win a Victoria Cross”.

However, the Daily Mirror of January 26, 1915, ran the story under the headline: “The First Indian to Win the Victoria Cross.”

Segregating people according to religion can have consequences, as we have seen in Ireland, or in India, where Lord Curzon, as viceroy, partitioned Bengal in 1905. He pitched Hindus and Muslims against each other and set in motion events leading to the secession

of East Pakistan and the creation of Bangladesh. Who is to say that there won’t be demands for the partition of parts of England 50 or 100 years from now?

That said, the Royal British Legion has endorsed the use of the khadi poppy devised by Lord Jitesh Gadhia as a gesture towards Indian soldiers. It was worn by rival captains

Virat Kohli and Joe Root during the India-England Test at the Oval in September.

The special poppy was also in evidence in Trafalgar Square last weekend, when London mayor Sadiq Khan paid “tribute to the incredible bravery of the people of India who selflessly sacrificed their lives for our freedom”.

Catherine Davies, the Legion’s head of remembrance, said: “The Legion wants to honour India’s vital contribution to the First World War and wearing the poppy made of

khadi is an important and symbolic way to do this.”

The statistics are that in the First World War, 1.5 million Indian troops fought for Britain between 1914-18 on the Western Front, in Gallipoli, Mesopotamia, Egypt and Italy. When it ended, 113,743 Indians were reported dead, wounded or missing.

India gave £100 million at the start of the war and between £20m and £30m per annum for the next three year. The cemeteries of Europe, the Middle East and Africa are littered with Indian dead. Without the support of the Indian army, Britain would probably have struggled

to win the war.

One hopes that for the first time, the Festival of Remembrance at the Royal Albert Hall next Saturday (10) will adequately reflect the Indian contribution to a war not its own,

and fought at a time when India was struggling for its own freedom.

Nigel Farage

Nigel Farage Rupert LoweGetty Images

Rupert LoweGetty Images

Rajan offers the pind daan in honour of his father and ancestors

Rajan offers the pind daan in honour of his father and ancestors

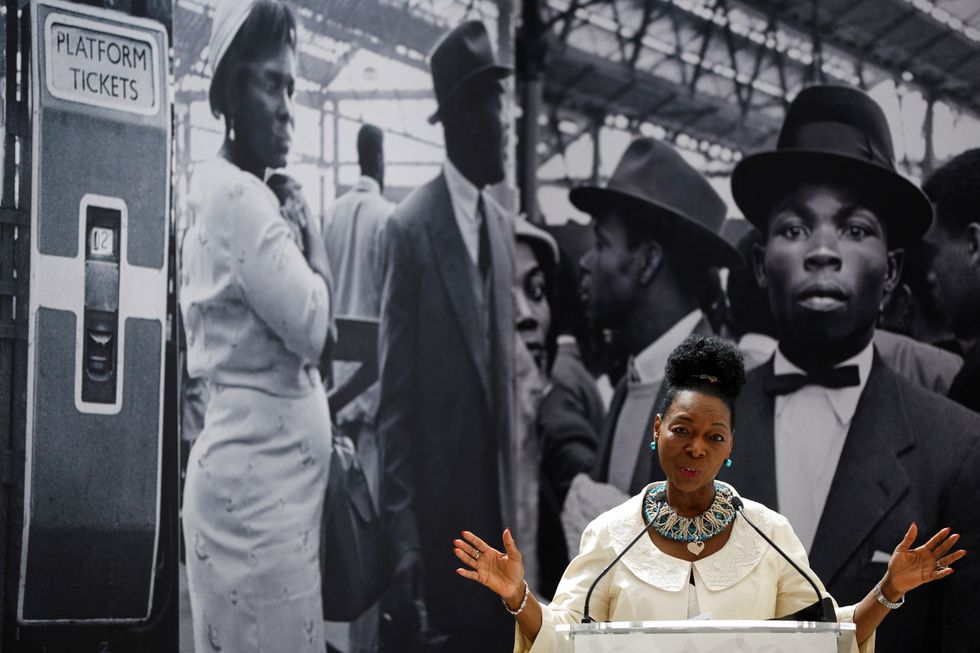

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’

Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’ Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’

Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’ Mahira Khan

Mahira Khan ‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience

‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’

Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’  John Abraham

John Abraham Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal

Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal  Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut

Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut Sana Yousuf

Sana Yousuf