AS I stepped into the Madras Club, I also took a step back for one brief, shining moment into my father’s youth. He was a clubbish sort of man, and even built one, the Kitchener Road Railway Colony Club in the early 1950s.

There was no club-house there, so he, a young, newly married officer, took it upon himself and created that club, including a children’s room with its own weekly newsletter; he loved children and we were lucky to have him.

TPS ‘Patty’ Kent, sportsman, bon vivant, brilliant administrator, had followed his father, Dr SS Kent, into the Indian Railways.

Dr Kent was the first Indian medical officer to be recruited on the then British Indian Railways in 1924. He became a great club-man, with his wife, Rajbans. They were a popular couple, and my grandfather partially explained that by saying that – while Indian women stayed at home, and their husbands would not countenance another man putting his arms around his wife at club dances – my grandmother Raj learnt ballroom dancing, played bridge, smoked, and kept up with the Joneses.

That was the heyday of English clubs in India. It was a domain for the whites, where they could forget they were in the brown man’s land, though a few were allowed to enter.

Madras Club in 1890My father, the eldest of five, spent his growing years in clubs, swimming, playing tennis and dancing. When he signed on to the Indian railways in Jamalpur in 1946-1947, there was no hostel for the lads, so he and his small batch of well-educated lads from good families, including AC ‘Bacho’ Puri, his lifelong friend, lived at the Jamalpur Gymkhana Club like burra sahibs, played sports and ate excellent meals while training to become engineers.

In 1947, the English were packing their bags and the clubs were still intact.

For me, stepping into the Madras Club on August 1, 2024, brought back memories of happier family times that vanished long ago like wood-smoke.

It is truly grand, spread over 14 vast acres, with several buildings and venerable trees, including the ancient banyan that had long sheltered dance bands playing under its branches.

When the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII, visited Madras, he danced to the music of one such band. Trouble is, he spent the entire evening dancing with the prettiest girl there, much to the chagrin of matrons and debutantes. Edward VII was notorious for his mistresses, including Alice Keppel, the great-grandmother of Queen Camilla.

Founded in 1832, the club moved twice before acquiring the Adyar Club. Quietly flows the Adyar at the bottom of the garden, and rowers from the nearby Boat Club can be spotted on the river.

In his excellent book, The Ace of Clubs, S Muthiah meticulously traces the entire history of the club and the changing social mores over the decades.

In 1961, Queen Elizabeth II conferred an MBE on Dorothy Banks in the Ballroom. After the Raj returned to England, the whites-only club opened its doors to Indians in 1956. What took it so long?

Lady Mohini Kent Noon with V SriramThe present building dates back to 1790. Built by George Moubray, accountant general of the East India Company, who bought 105 acres of land on the banks of the Adyar for his hunting lodge – just imagine the grandeur of his main residence.

Moubray’s Cupola, as it is still called, is an octagonal structure in the Indo-Saracenic style that sits atop the building like the cherry on a royal wedding cake. Moubray spent weekends there, and in the hot weather he slept in the cellar, and in the cooler months he slept in the cupola with the windows open (all sides have long windows) and the breeze, cooled by the Adyar waters, must have been heavenly. There’s an urn on top of the cupola, but that can’t contain Moubray’s ashes since he returned to England in 1792-1793.

I was in Madras, now Chennai, for ayurvedic treatment at the private clinic of Dr Sudhir and Dr Mayadevi. It was a blessing to return to Room 6 after the morning’s treatment, and order in lunch. The food is delicious, the menu extensive, and prices low. Apart from the formal dining room, there’s a casual poolside café. They offer north and south Indian, continental and pan-Asian dishes, plus some innovative ones such as the dry French beans cooked in Lea & Perrins sauce, one of the sauces developed by the Raj, and one of the few food legacies they left behind.

The staff is courteous, and one evening, after I had eaten superb vegetable cutlets in the dining room, the major domo asked in a soft Jeeves-like voice if ‘madam would like dessert’. How could I refuse? The caramel custard, another staple of the Raj, was priced at just over one pound.

Dishes of yore, such as pish-pash, kedgeree and other nightmares, left these shores with the last British soldier who marched out of India.

Kiran RaoKiran Rao had checked me in as her guest. A successful businesswoman and entrepreneur, with sugar factories and the fashionable Amethyst arcade that offers cafes, designer clothes and interior design, she’s a leading light of the Club.

Among other things, she found a solution to the terrible acoustics inevitable in such an old building. The original ceiling of small bricks, wooden beams and lime water must be allowed to breathe, so a false ceiling is out. With the help of a sound engineer, she created baffles of thick sheets of rubber encased in white muslin suspended from the ceiling, which absorbs the sound and also looks tasteful.

An animal lover, Kiran has rescued 300 stray dogs from the streets whom she accommodates at her house and farm, and where she pampers them.

To know the Madras Club is to love her, and when Sanjay Madhavan, CEO Infonovum Technologies, returned to Chennai after years in Switzerland, his priority was to live near the club where he had grown up watching movies on Sunday nights and revelling in love-trysts up in the cupola, which is now closed to lovers, friends and foes alike.

I met him when he singing at the Club Music Night, accompanying Badri Vijayaraghavan, a well-known singer in Chennai. They sang songs of my vintage, so I enjoyed it hugely. People were dancing and there was much joy in the air.

It is obvious these old clubs are once again inching towards another golden period.

On Sunday morning V Sriram, columnist and heritage activist, took us for a walk down memory lane in the club. The turnout was impressive – dozens of people had made the effort to assemble at 8am on the broad terrace.

He pointed out a large marble slab engraved with the names of club members who died in the first World War. Sir Edwin Lutyens of Delhi fame had been commissioned to create that memorial, but dragged his heels for fifteen years.

A band performing at the clubHis reluctance may have been due to the fact that his wife, Lady Emily Lutyens, decamped to Madras often, mesmerised by the young handsome J Krishnamurthy, who lived at the nearby Theosophical Society. She even missed an important dinner in Delhi with the Viceroy, because of the handsome, but her husband forgave her, which is more than an Indian husband would ever do.

The magnificent swimming pool now has a secure boundary wall, but Sriram explained that earlier it opened on to mangrove trees where lived a herd of swine. One day a pig, wanting a change from the Adyar river, plunged into the pool. When a young lad excitedly ran home to report: ‘Dad, a pig jumped into the pool today!’ his father sternly rebuked him, saying: ‘That’s no way to talk about a member of the club!’

Actress Bella Thorne and Charlie Puth attend the Y100's Jingle Ball 2016Getty Images

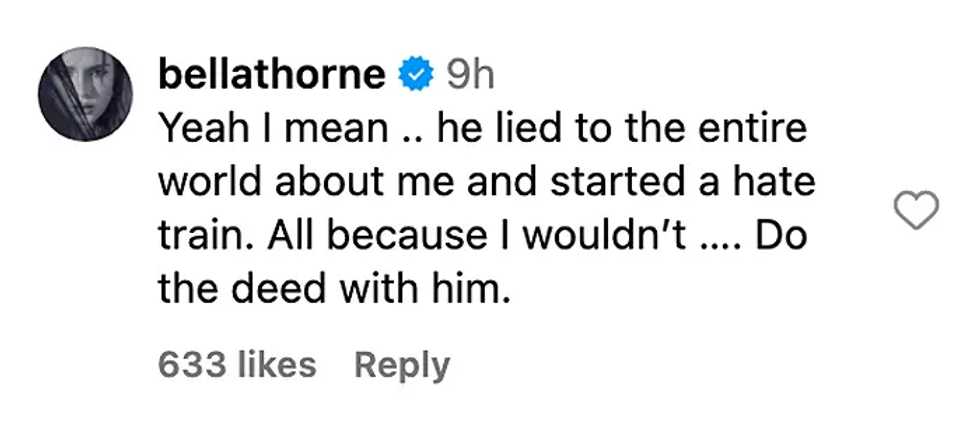

Actress Bella Thorne and Charlie Puth attend the Y100's Jingle Ball 2016Getty Images  Bella Thorne's commentInstagram Screengrab

Bella Thorne's commentInstagram Screengrab  Charlie Puth performs onstage at an interactive global eConcert liveGetty Images

Charlie Puth performs onstage at an interactive global eConcert liveGetty Images  Bella Thorne and Mark Emms attend a red carpet for the movie "Priscilla"Getty Images

Bella Thorne and Mark Emms attend a red carpet for the movie "Priscilla"Getty Images Charlie Puth and Brooke Sansone attend the 10th Breakthrough Prize CeremonyGetty Images

Charlie Puth and Brooke Sansone attend the 10th Breakthrough Prize CeremonyGetty Images