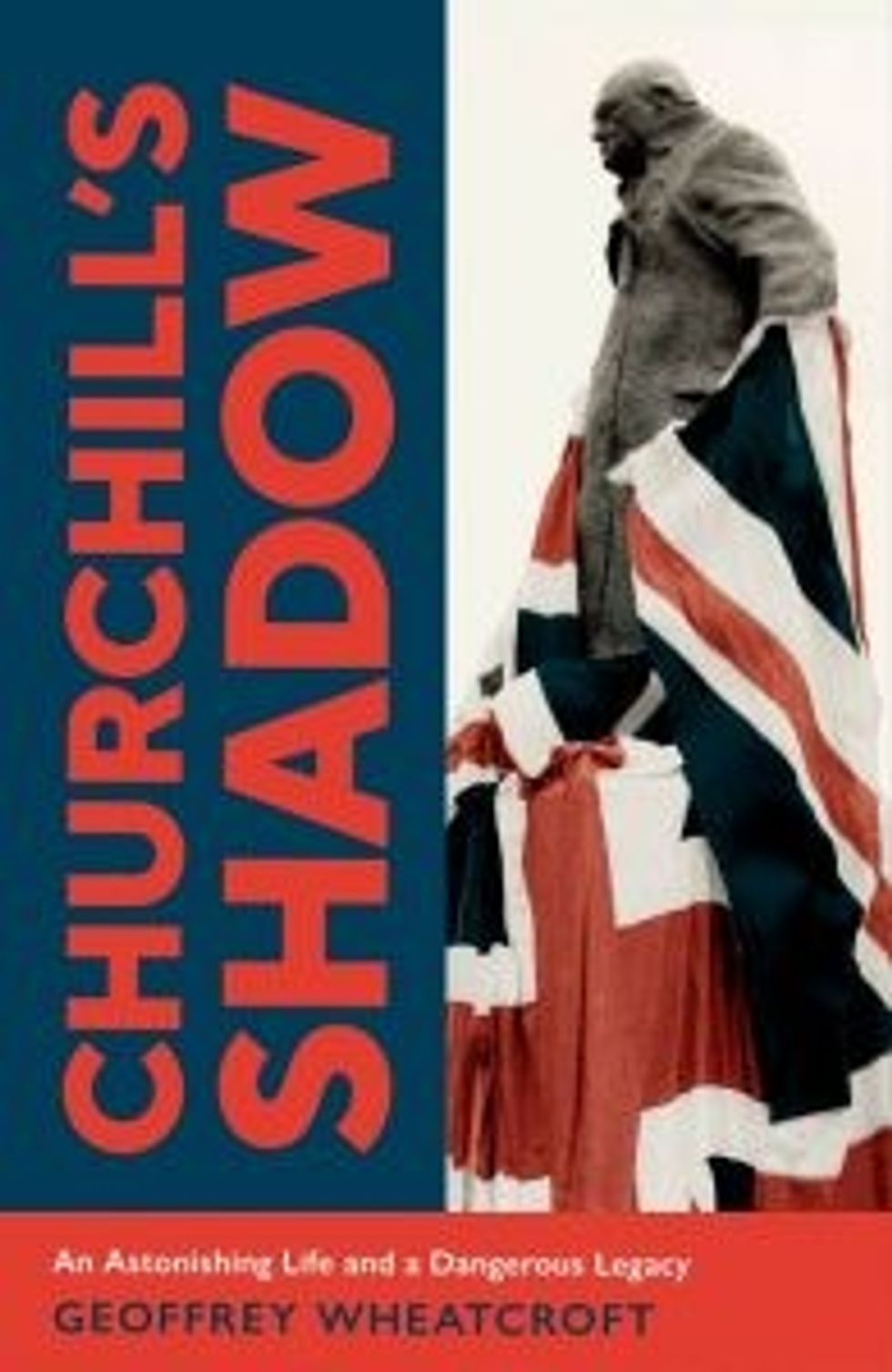

Author offers 'alternative account' of Britain's war-time leader in new book

GEOFFREY WHEATCROFT’S new book on Sir Winston Churchill offers readers probably the most balanced view of Britain’s wartime prime minister.

Talking to Eastern Eye about Churchill’s Shadow: An Astonishing Life and a Dangerous Legacy, the author said: “I did not set out to write a hostile or revisionist or contrarian account of Churchill.

“I think of it more as an alternative account because so many of the books about Churchill are uncritical and sometimes adoring. It is very difficult to get to terms with him because he has become such a heroic figure who stands outside the realms of history.”

He stressed: “Churchill is very difficult precisely because there are so many extremes. The extreme of 1940 when he genuinely was a heroic figure whose defiance of Hitler changed the course of history – and for the better, because Hitler was defeated.

“And then there is Churchill and the 1943 Bengal famine, where attempts to defend him are completely hopeless. His view of Indians was one of racist contempt. And so it is right to try and understand what he did for this country in 1940, but it’s no good trying to dismiss his imperialism and racism.”

Churchill, who was born in 1874 and honoured with a state funeral in 1965, spent 19 months in India as a young officer with the 4th Hussars from 1896. He served as Tory prime minister from 1940 to 1945, “was emphatically rejected by the British electorate” in the 1945 general election in favour of Labour, and was an ineffective prime minister from 1951 to 1955.

Having started in the army, Churchill’s career combined well-paid journalism with politics.

He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1953, but because he employed researchers and ghost writers, Wheatcroft writes that “by the 1930s, it is often difficult to know how much of the books and journalism he published was actually written by him”.

Wheatcroft, who read modern history at Oxford, is a distinguished author and journalist who was once literary editor of The Spectator.

The book asserts: “For so long a bitter controversial figure, intensely disliked and distrusted, he was transformed at one extraordinary moment into a superhuman hero, and then gradually acquired an almost mythical status which made it hard to distinguish fact from fiction.

“His legacy is flawed, and his posthumous influence has been little short of disastrous. So, far from being a universal oracle of wisdom and virtue, few great men have been wrong so often, have made so many mistakes, or have held so many opinions and prejudices which were repugnant even at the time.”

For example, Churchill not only set himself against Indian independence, but he also opposed votes for women.

The book acknowledges: “While the English hadn’t invented the sectarian conflict in India, they had sometimes exploited it, but Churchill was almost unique in wanting to encourage it. ‘Winston rejoiced,’ (senior civil servant, Jock) Collville recorded in April 1940, ‘in the quarrel which had broken out afresh between Hindus and Muslims. Said he hoped it would remain bitter and bloody.”

Wheatcroft finds that assigning guilt to the cause of the 1943 Bengal Famine is “complex”, “but Churchill’s partisans have a hopeless task when they try to defend his conduct during the famine”.

“Churchill said, ‘The starvation of anyway underfed Bengalis matters less than that of sturdy Greeks,’” records Wheatcroft.

He also notes Churchill’s view that “the Hindus were a foul race protected by their mere pollulation from the doom that is their due”.

Churchill’s secretary of state for India, Leo Amery, said, “I am by no means quite sure whether on this subject of India he is really quite sane.”

On Churchill movies, of which there have been many, he says: “Both Churchill and Darkest Hour were heroic fantasies, whose connection with reality was tenuous.”

Wheatcroft has written about “the truly extraordinary growth of the Churchill cult in America”.

He told Eastern Eye that when his book proposal was on the market looking for a home, a reputable New York publisher “wrote to me personally saying that he was afraid he wasn’t going to take my book. He said, ‘I really like your idea of trying to distinguish between ‘Churchill the man’ and ‘Churchill the myth’, but I am afraid what the public still wants is the myth.’

“I couldn’t help laughing at that, but I didn’t think the myth can persist all that much longer. I believe a process of reassessment is taking place, I’m fairly sure of it. To take a random example, Daniel Finkelstein, who writes in the Times and is also a Conservative peer, wrote a column two or three years ago about Churchill. ‘Was Churchill a racist? And was he a hero who saved the country? Yes, he was both of those things.’”

Wheatcroft said: “It’s the defiance of some of the Churchillians who refuse to concede any kind of criticism of Churchill which is ridiculous. It’s going to become an untenable position. That kind of Churchill worship has reached its pinnacle now. We will not see it in that way much longer. Not least because every single time Churchill’s name has been invoked on some cause or other, it has led to disaster, including Afghanistan and Iraq.”

As a young man in Bangalore, where Churchill played polo, “he was able to maintain three personal Indian servants, a butler, a dressing boy or valet, and a groom”.

It was the only time he visited India. The experience “left him full of contempt for Indians. The only Indians that he had met were servants, and beggars he passed in the street.

“Lord Curzon, who was viceroy in the early 1900s, was a pure imperialist. He believed in the British imperial mission. He was praised by (India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal) Nehru much later for his work in preserving the architectural and artistic fabric of India. He thought that India had a rich culture. Churchill was utterly contemptuous of Indian culture.”

Churchill’s attitude to Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was also “deplorable”. The two met only once – briefly – in November 1906 when Gandhi came to London from South Africa to plead the cause of Indians who were suffering discrimination. Churchill, then a junior minister to the colonial secretary, “spoke nicely”, said Gandhi, who made no impression at the time on the Englishman.

Later, Churchill became obsessed with the “naked fakir” who had the temerity to negotiate with the British rulers and even the King Emperor on equal terms.

Churchill strongly condemned the Amritsar Massacre of 1919, “and yet he did have completely retrograde views on race,” the author pointed out. “Other people’s views on race were changing. By the 1930s, many Englishmen did not think in terms of higher grade races. Although, of course, Hitler did. What made Churchill that way was he formed his views on empire, races, India, at the end of the 19th century, and he never changed them. Most people’s attitude to empire and race softened, whereas his hardened, and he was still a bigoted racist in the 1950s. He just didn’t grow up.”

Churchill College, Cambridge, named after the leader, was attacked recently for holding discussions on “Churchill, Empire and Race” but Wheatcroft spoke up for the institution. “There’s no reason why they shouldn’t discuss or debate Churchill just because they are named after him.

“The idea that it was blasphemy for Churchill College even to enter into debate about Churchill’s life and character is absurd. Of course, they should. He should not be treated as some strange character beyond the realms of history and a man of myth. He should be treated as a historical figure who can be discussed objectively and with detachment.”

Asked for what might be a sensible British Asian attitude to Churchill, Wheatcroft suggested: “They must certainly see that on the Bengal famine, Churchill was absolutely indefensible.

“But it’s possible to deplore that and, at the same time, very much to admire him because we would be living in a part of the Third Reich if it hadn’t been for Churchill. And that would have been no fun for Indians.”

Churchill’s Shadow: An Astonishing Life and a Dangerous Legacy, by Geoffrey Wheatcroft. The Bodley Head; £25

Priyanka Chopra calls herself nascent in Hollywood as 'Heads of State' streams on Prime VideoGetty Images

Priyanka Chopra calls herself nascent in Hollywood as 'Heads of State' streams on Prime VideoGetty Images  Priyanka Chopra wants to build her English film portfolio after Bollywood successGetty Images

Priyanka Chopra wants to build her English film portfolio after Bollywood successGetty Images  Ilya Naishuller, Priyanka Chopra and John Cena attend the special screening for "Head of State" Getty Images

Ilya Naishuller, Priyanka Chopra and John Cena attend the special screening for "Head of State" Getty Images

Arijit Singh performing Instagram/

Arijit Singh performing Instagram/ Arijit Singh clicked during a performance Getty Images

Arijit Singh clicked during a performance Getty Images

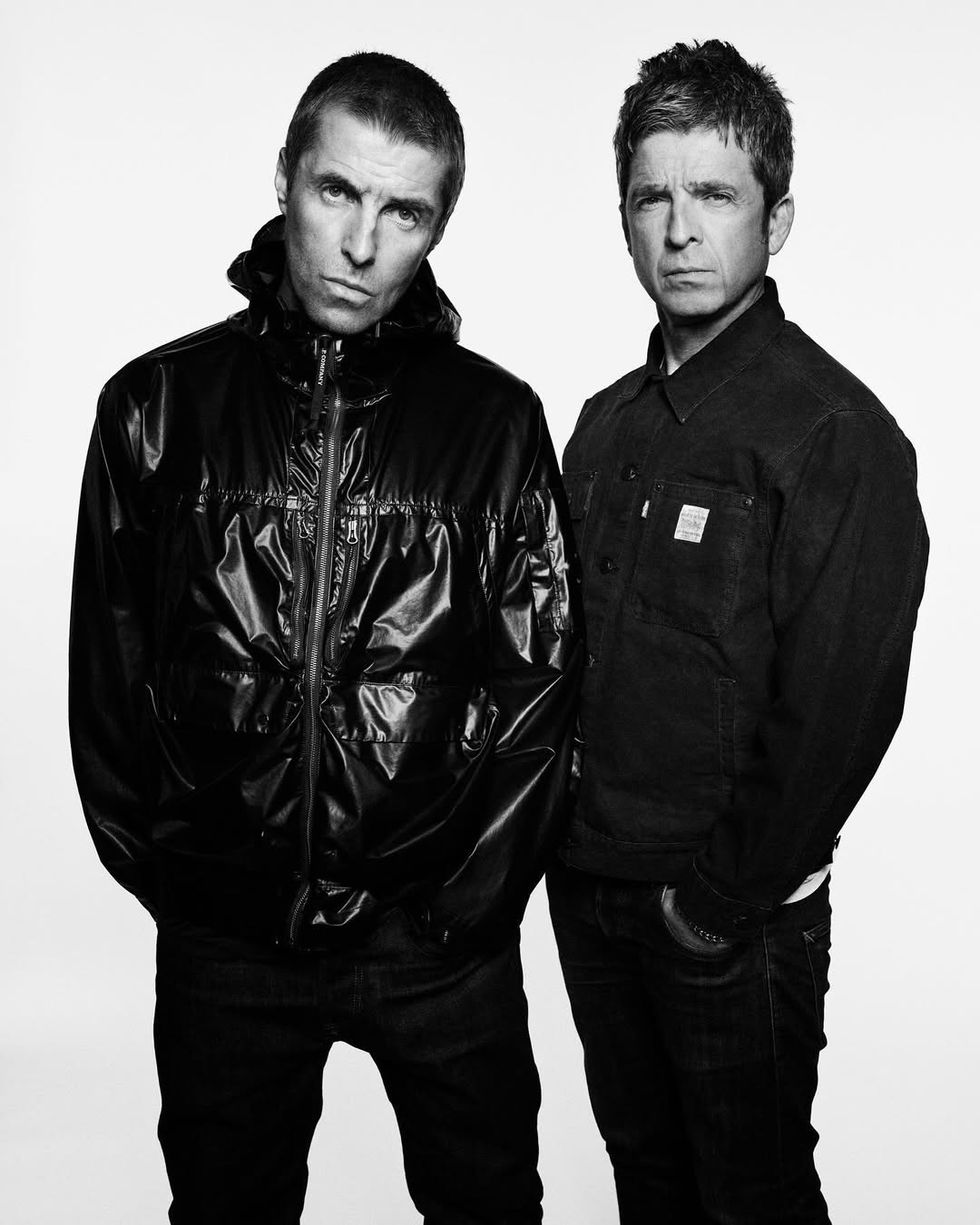

Liam Gallagher accepts Oasis' award for 'Best Album of 30 Years' Getty Images

Liam Gallagher accepts Oasis' award for 'Best Album of 30 Years' Getty Images  Liam Gallagher plays to a sell out crowd at the Universal AmphitheatreGetty Images

Liam Gallagher plays to a sell out crowd at the Universal AmphitheatreGetty Images Liam and Noel Gallagher perform together in Cardiff for the first time since 2009 Instagram/oasis

Liam and Noel Gallagher perform together in Cardiff for the first time since 2009 Instagram/oasis