PRETI TANEJA ON HER LITERARY JOURNEY AND FEMINIST EVENT AT ALCHEMY

ALTHOUGH performance plays a big part at the annual Alchemy festival, there is always a strong literary element, and inspiring event Sharper Than A Serpent’s Tooth: South Asian Feminist Writing will provide that this year.

Acclaimed writers Preti Taneja and Mona Arshi will discuss their work in a conversation led by journalist, critic and Arifa Akbar, along with exploring ideas and legacy. I caught up with British author Preti to talk about the event and her own literary journey...

What first connected you to writing?

As a child, I spent hours reading in bookshops, in libraries, at home and even in the car. It was an intense pleasure and a refuge from the rest of the world. And my mother, Meera Taneja, was a brilliant and innovative cook; her eight cookery books were published in the UK in the 1970s and 80s. So I was used to seeing a writer at work. She spent long hours in her study slaving over manuscripts until I was about seven. Eventually, she started her own food business from our kitchen.

How did you feel when you completed your first book?

When the finished copies of We That Are Young arrived, it felt like being warmed by the sun. I had this overwhelming sense of gratitude to everyone who had got me and the book to that point. It’s a privilege, and it takes generations of work to have the freedom to fulfil such dreams.

Do you have a writing process?

It always begins with snatches of ideas and lines scribbled in notebooks. When it comes to words on the page, I just go for it, to get the voice down. I usually have a setting in mind and do a lot of research on place and details as I go. I redraft a lot,, structuring chapters and every sentence. I have a bad habit of not getting up from my desk enough. I can sit there all day, eight hours. Of course 90 per cent of what comes out gets binned. But if there’s something worth saving, it’s obvious.

What key advice would you give to aspiring writers?

Listen to the world around you and be alive to how your own experiences can be drawn on for your work. Read everything, from adverts, tweets and memoirs, to novels in translation, classics and new fiction. Write and take it seriously. It takes sacrifices that you have to want to make for their own sake. Success is in doing the work and making it the best you feel it can be. Keep revising and sending it out! Trust the process.

What are your favourite themes to cover?

I worked for UK charities and then international NGOs for over a decade before I became a writer. I also now teach writing and human rights, and writing in prisons. I’ve spent time in some incredibly-challenging environments with people who have survived immense hardship and are making art, telling their own stories, creating new culture in extreme circumstances, because that’s a human imperative. Exposing social injustice and exploring the threads that connect us despite divisive, constructed hierarchies of caste, race, class and so on is at the heart of what I’m interested in.

How much are you looking forward to participating in Alchemy?

One of the lovely things about finally getting published is being asked to participate in events I’ve always enjoyed from the crowd. It’s wonderful to be programmed alongside Mona Arshi, whose poetry works language into fire.

What can we expect from the event?

Both Mona and I will read and talk about our work with journalist Arifa Akbar, so three strong, creative women in one go! We may cover themes from gender and sexuality to writing or politics; it could get intense.

Do you think things like social media are disconnecting people from books?

I actually think social media is a great way of finding out about books that you might want to read, as well as what’s being sold in chain bookshops at the front tables. Online, you can find and follow small, independent publishers who are putting out exciting and experimental work. You can find readers who like the same poets and books as you. You can also connect with books bloggers who read differently from what gets reviewed in the mainstream press, and that’s really necessary.

Do we need more strong female voices?

We have them, we are them; they have to be very strong to get into the mainstream, so the more we have, the less that will matter and the easier it will be to be heard. Critical mass is important.

What can we expect next from you?

I’m working on an idea that is going to be set in the UK, probably in the North East where I partly grew up.

What inspires you?

Fearless people, especially women, who have the courage of their convictions and take risks for what they believe in and support each other. I hope I can be like that and pass it on too.

Who is your own literary hero?

I love books that bring radical ideas to life, and writing that challenges the status quo. So Toni Morrison is one, and JM Coetzee is another. Gertrude Stein, a writer who basically broke language, Adrienne Rich and Claudia Rankine, both poets I come back to over and over. I think Mahasweta Devi and Manto are both heroic in their form and the stories they tell.

What is your own personal favourite book of all-time?

Toughest question ever! Meera Taneja’s Indian Cookery, which is dedicated to my sister and I. Each recipe comes with a short introductory story, often a vignette from our home. It’s a testimony to an early 1980s world of Asian families in Britain, celebrating Indian culture, speaking to the new country and carving a space for the future. It’s a world rarely documented outside our family albums, although that is changing. I still cook from it, and I can hear her voice in the lines.

Why do you love writing?

There’s nothing like the feeling of being inside a world immersed. While you are writing it, it’s revealing itself to you. I love working deep into the fine grain of words and all their infinite meanings.

- Sharper Than A Serpent’s Tooth: South Asian Feminist Writing takes place at Purcell Room, Southbank Centre in London on May 5 2018 at 7.45pm as part of Alchemy. Tickets and further information available at www.south bankcentre.co.u

Shashi Tharoor

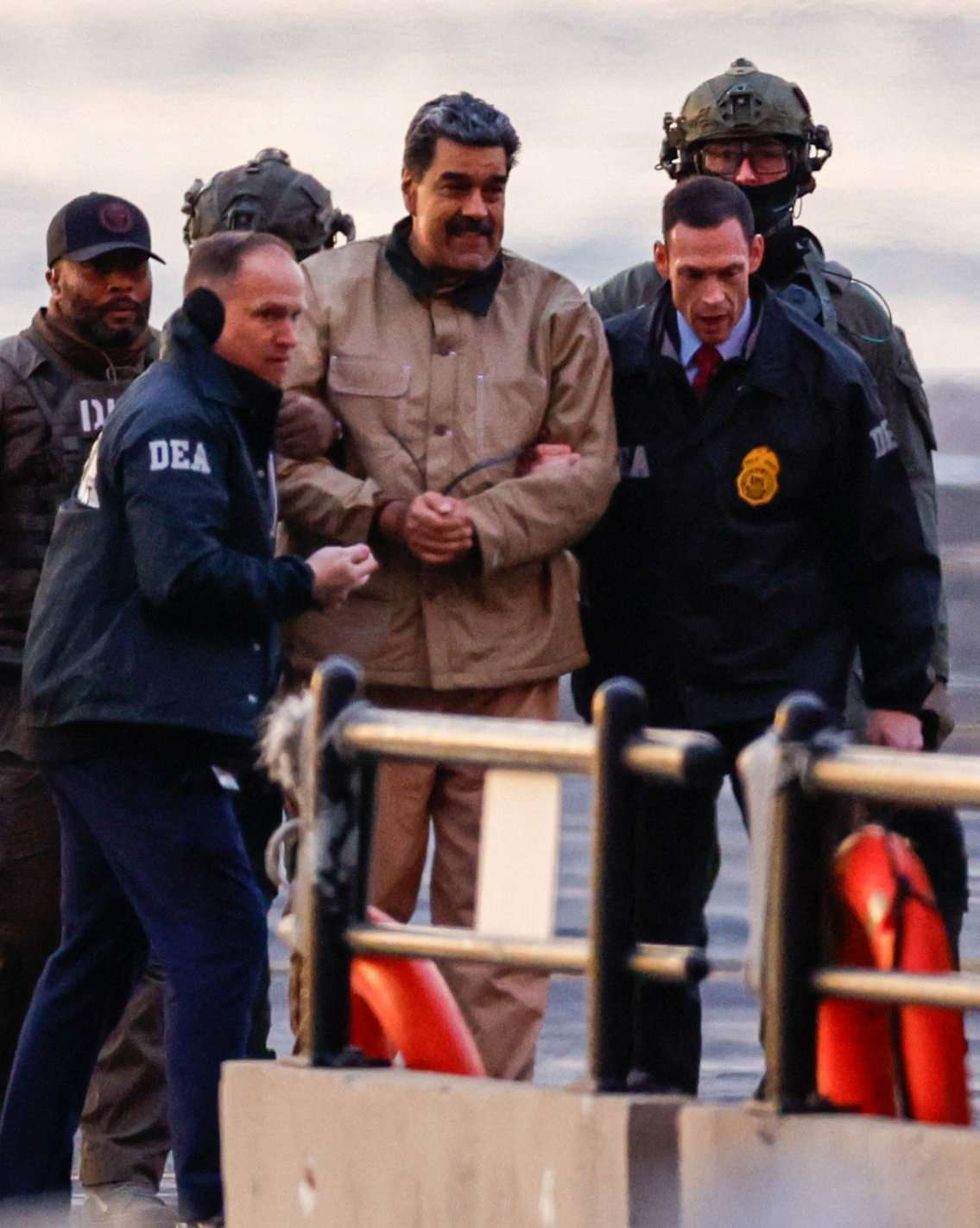

Shashi Tharoor Nicolás Maduro arriving at the Down town Manhattan Heliport.

Nicolás Maduro arriving at the Down town Manhattan Heliport.