by KISHWAR DESAI

FIRST the British tried to silence them, then they tried to kill them, and then those who survived were tortured, jailed, whipped and even bombed under martial law.

This was the fate of many of the residents of Amritsar, and other cities of undivided Punjab in 1919. And who were these unfortunate targets? Those who had decided to join Mahatma Gandhi’s Satyagraha against the brutal Rowlatt Act, which was designed to suppress and incarcerate political protesters.

Saturday (13) marks the centenary of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, in which more than 1,000 people were killed by Brigadier General Reginald Dyer. He ordered 1,650 rounds to be fired upon them for 10 minutes, without any warning, while they were attending a peaceful political meeting at the Bagh.

The horrific attack was the spark that lit the flame of India’s freedom struggle, and united those determined to achieve independence from colonial rule.

On April, 13, 1919, thousands from Amritsar, along with a few from elsewhere, had gathered at the venue to convey their unhappiness against the arrest of Gandhi, as well as that of local leaders, including Dr Saifuddin Kitchlew and Dr Satya Pal. The leaders had been arrested for organising a very successful Satyagraha movement – which had begun two weeks earlier – against the Rowlatt Act.

There were other causes of unhappiness in Punjab, especially against the regime of intimidation unleashed by the-then Punjab lieutenant governor, Sir Michael O’Dwyer, who ruled with an iron hand. Inflation was high, an influenza epidemic had taken hundreds of lives, and the forced recruitment of soldiers to the British Army fighting the First World War

added to the miseries of people.

It was a Sunday and the Bagh was a popular meeting place. Some visitors travelled from other districts to celebrate the harvest festival of Baisakhi, as well as the establishment of the Khalsa Panth by Guru Gobind Singh.

The Bagh was not a garden – as is often thought because of its name – but a barren, undulating piece of land of around six and-a-half acres, very close to the Golden Temple (Sikhism’s holiest shrine). It had only one narrow exit, and was surrounded by a boundary wall, with houses backing onto it.

However, even though the meeting of thousands of Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims was peaceful, the British were unnerved both by the numbers, and the show of Hindu-Muslim unity, despite their policy of divide and rule.

There had already been violence in the city on April 10, when at least 30 Indians had been shot and killed by British troops in Amritsar. In retaliatory action by the protesters, British property was burnt, five European men were killed, and one woman was badly injured, while another was threatened with assault. There was a collective shock among the local British regime that Indians had dared to retaliate, even though at least five times more Indians had been shot dead in the disturbances of April 10.

There was undoubtedly a desire (often expressed and recorded in official documents) that Indians needed to be ‘taught a lesson’. There is enough circumstantial evidence to prove Dyer was hand-picked for the job, possibly by O’Dwyer, who judiciously stayed away while the disturbances were going on. He remained in Lahore, attending his farewell parties,

as he was due to retire.

On the morning of April 13, Dyer had banned public meetings through cursory proclamations, but none of the announcements were made near the Bagh, nor, deliberately, were people prevented by the police from gathering there. An aeroplane flew over the Bagh around 4pm to inform Dyer when sufficient people were present. He then marched through the only narrow entrance (and exit) with his troops, comprising Baluchis and Gurkhas – he was careful not to take any British soldiers with him. Dyer ordered firing on the crowd as soon as he entered, without any announcement for dispersal.

Hundreds of Indians died on the spot, and others, when they tried to escape, were unable to do so as Dyer had not only blocked the path, he had also stationed armoured vehicles outside the Bagh with machine guns in case anyone managed to get out.

Some victims lay down to avoid the bullets, and others ran to try to scale the walls on the periphery of the Bagh. A large number of corpses piled up near the walls and many of the wounded were crushed under the weight of bodies on top of them. At least 120 reportedly fell into a well on the grounds, which did not have a rim encircling it, while trying to escape

the bullets.

Many of the injured had multiple wounds – and as curfew set in shortly afterwards, hundreds bled to death through the night. Dyer had made no provision for medical help. The wounded who managed to survive were turned away from the civil hospital – the civil surgeon called them ‘rabid dogs’ and told them to seek medical treatment from Gandhi and others.

Indian doctors who treated patients at home recalled many of the injuries were on the back, legs and soles of their feet. They also remembered that the police came around to inquire who had been treated for injuries, possibly to identify and arrest them for sedition. Relatives were forced to take the corpses away either stealthily at night, or the next day, for mass burials or cremation. At least 45 corpses remained unidentified.

A detailed count of the casualties and collection of names was not immediately carried out by the British: as a result, the numbers officially recorded months later were much lower than what the death toll would have actually been. Even a compilation of the data available today indicates there would have been more than 500 dead, but it is also known that many died in secrecy so as not to attract retribution on their families by the British. Eyewitness accounts say that around 1,000 died at the Bagh and perhaps twice that number were injured.

Despite the deaths and injuries of so many, the repressive regime under O’Dwyer did not cease its intimidation. Perhaps the rulers realised that the people were temporarily subdued, but not subjugated. Martial law was imposed all over Amritsar and in some other districts in Punjab, ensuring that no report, in any detail, of any of the atrocities taking

place, leaked out. Nor were those arrested allowed any legal help, as lawyers from outside were forbidden to enter Punjab during the period of martial law. Many lawyers in Amritsar and other cities had already been thrown into jail.

The martial law orders, such as the infamous ‘crawling order’ – where men were forced to crawl on their stomachs through a particular street in Amritsar – were meant to further humiliate and demean Punjab’s non-white population.

Amritsar, particularly, became like a concentration camp with guards posted on all gates of the walled city, checking anyone who wanted to enter or exit; and no one could exit without a valid pass from a British authority. In Lahore, also under martial law, at least 64 orders were passed by another army officer – the orders were whimsical, degrading and bizarre, all meant for the Indians.

When martial law was ultimately lifted, many leaders such as Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore condemned the situation in Punjab, and the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. Many of the eventual freedom fighters came together as they learned of the oppression Punjab had been under once the official (Hunter Committee) evidence began to be collected. However,

key parts of official evidence were to remain suppressed or censored for years.

Gandhi, along with Madan Mohan Malaviya and Pandit Moti Lal Nehru, also began to gather eyewitness accounts towards the end of 1919, and more of the truth was revealed.

While Dyer died of natural causes in 1927, O’Dwyer was assassinated by Udham Singh at Caxton Hall in London on March 13, 1940. Freedom fighters such as Singh had vowed to take revenge for the atrocities committed in 1919.

However, as Gandhi was to say, the rot that had entered the British system was systemic, and it was the system which needed to change. After Jallianwala Bagh, Indian leaders, including a young Jawaharlal Nehru, expressed their disillusionment with British rule. Within 28 years, India had got its freedom.

- Award-winning author Kishwar Desai’s new book Jallianwala Bagh, 1919, The Real Story has just been published. She is the chair of Taacht, which has set up the Partition Museum in Amritsar, as well as a collaborative exhibition on Jallianwala Bagh, which is set to open at the Manchester Museum on Thursday (11). The exhibition will also begin at the Nehru Centre in London on Friday (12) as well as at the Birmingham Library.

Nigel Farage

Nigel Farage Rupert LoweGetty Images

Rupert LoweGetty Images

Rajan offers the pind daan in honour of his father and ancestors

Rajan offers the pind daan in honour of his father and ancestors

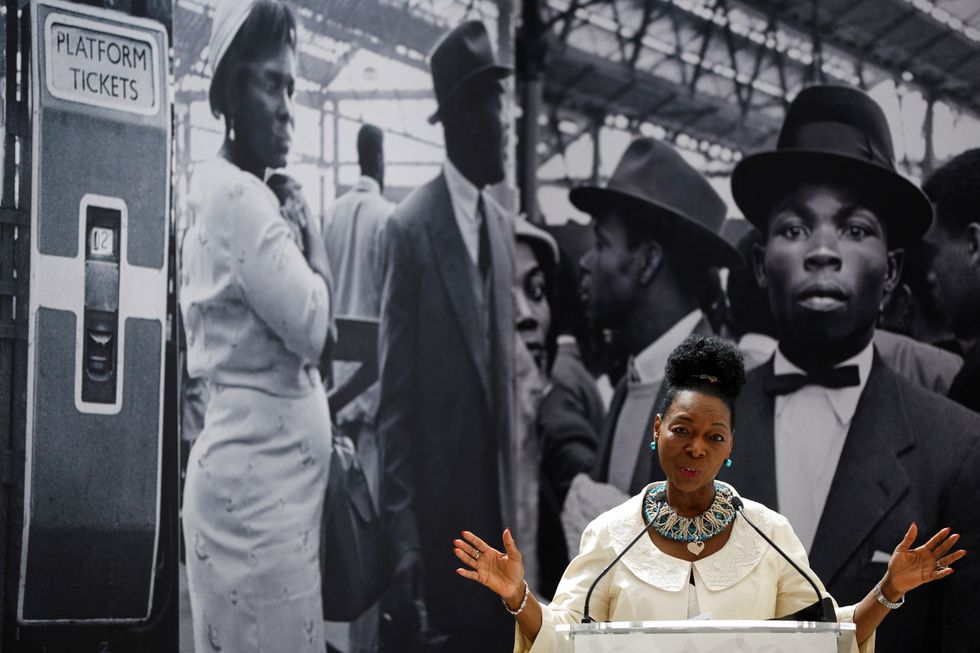

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’

Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’ Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’

Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’ Mahira Khan

Mahira Khan ‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience

‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’

Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’  John Abraham

John Abraham Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal

Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal  Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut

Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut Sana Yousuf

Sana Yousuf