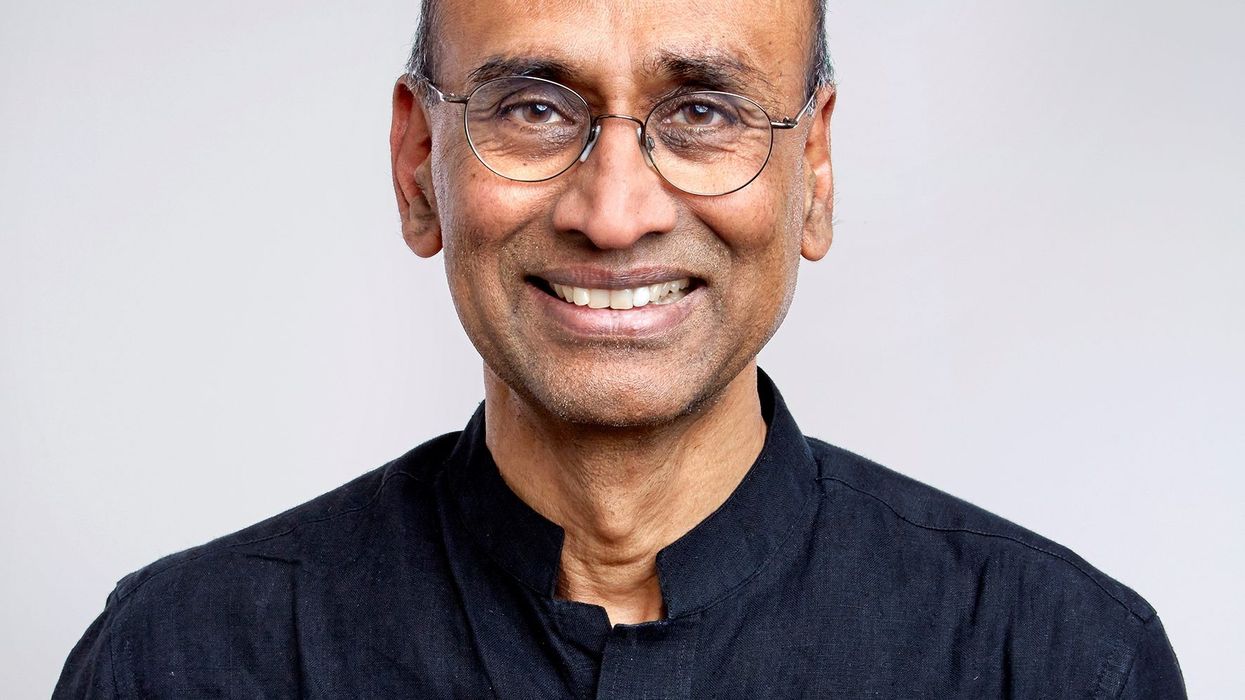

PROFESSOR Sir Venkatraman (“Venki”) Ramakrishnan, winner of the 2009 Nobel Prize for chemistry, was for five years president of the Royal Society, the organisation which brings together the world’s top scientists.

Set up in 1660 under a royal charter granted by King Charles II, Venki was the first person of Indian origin to hold the post.

As president, he had wanted to deal with a number of big issues such as the need to have a “broad-based” education, both at school and at university, so that everyone in society has some knowledge of both the sciences and the arts.

“In fact, my entire term was hijacked by two issues – Brexit and how we deal with Brexit.

And the second is the whole pandemic, and what we could provide as a science community to help with the pandemic,” he tells GG2.

He stepped down as president in December 2020 after nearly a year of advising the government on the pandemic. In April 2020, he joined the government’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) and was an early proponent of wearing face coverings as a way of slowing down the spread of the virus.

Venki’s arguments were crucial in helping to convince the government that masks were, after all, a good idea.

“It used to be quite normal to have quite a few drinks and drive home, and it also used to be normal to drive without seatbelts,” says Venki. “Today, both of those would be considered anti-social, and not wearing face coverings in public should be regarded in the same way. If all of us wear one, we protect each other and thereby ourselves, reducing transmission. Not doing so increases the risk for everyone, from NHS workers to your grandmother. So just treat it as another item of clothing that is part of the new normal and wear it whenever you cannot socially distance safely.”

Venki warns: “There are no silver bullets but alongside hand washing and physical distancing, we also need everyone to start wearing face coverings, particularly indoors in enclosed public spaces where physical distancing is often not possible. Everyone should have a face covering and they should not leave home without having one in their possession”.

When the government came under fire for not coping with the pandemic and tried to shift the blame by insisting it had been “following the science”, Venki used all his authority to defend scientists.

“Ultimately, advisers advise, ministers decide,” he says when rebuking government ministers. “In these decisions, science advice is often only one of the things they need to consider. Science advice is not the same as simply ‘following the science’.”

He has also headed the Royal Society’s multi-disciplinary group, DELVE (Data Evaluation and Learning for Viral Epidemics), which gathered evidence on how countries around the world are tackling Covid-19. “It looks as if governments that are run by either technocrats or where the technocrats have a great deal of say, tend to do well. The opposite extreme is the US where Trump has constantly railed against scientists. At least the British government has been listening to scientists. Listening to scientific advice is actually extremely important.”

He goes on: “And there’s one other thing that DELVE has done, which is we didn’t just have scientists. We had natural scientists. We also had behavioural scientists, including world famous ones like Daniel Kahneman.

“And we had people like (Lord) Nick Stern and Tim Besley or world famous economists. And so the idea is, if you want a solution that has social implications, you need to look at all aspects of the problem, and try to optimise it globally.”

In dealing with the virus, he is not a great proponent of the “lives versus livelihood” theory. “The one thing that we’ve learned from other countries is that the best way to have an economic revival is to get on top of the virus. So Taiwan, Korea, Japan, China, their economies are actually recovering and doing better than countries which didn’t keep control of the virus. It’s not just about restrictions; people have to feel free to go out and shop, go to restaurant livelihoods is a false dichotomy. We should be looking at how to stay on top of the virus and how we can open up the economy in ways that don’t result in another surge. Those are lessons we can learn from looking at other countries, as well doing things here. Maybe we need to do things differently.”

In December 2019, he warned the Indian government that it was taking a “wrong turn” over its Citizenship Amendment Bill.

As president, he often appeared on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme, on the Andrew Marr Show on BBC TV, given a valedictory interview to the Financial Times and done a Royal Society zoom “conversation” with Stephen Fry, which was almost entirely monopolised by the celebrity broadcaster.

Now that he is no longer president, he is more than happy to return to his “day job” as a research scientist at the Medical Research Council’s Laboratory for Molecular Research in Cambridge. This is where he did his work on the ribosome which led to the Nobel Prize, which he shared with two other scientists. Venki had settled in Cambridge in 1999 after a career in the US, where he went at 19 after getting his first degree in Baroda. Now 69, he was born in Tamil Nadu, the son of two scientists.

“At heart, I’m a scientist,” he says. Returning to more of a normal life “won’t involve as much travelling and schmoozing”, he jokes.

For the last five years, he felt distracted as his time was split between his home and lab in Cambridge, and the headquarters of the Royal Society in Carlton Gardens, London, where he was given an apartment.

“It’s been a bizarre five years,” he muses. “I enjoyed parts of it. The thing I enjoyed most was meeting very interesting people. Once you get a Nobel Prize you do have that opportunity.

But if you are president of the Royal Society, it just happens almost as part of your job. And so it was very interesting to meet, not only scientists from different branches of science and from different countries, but also people from other walks of life.

“And the other interesting thing was to get a feel for how government views science, and how to be that interface between the science community and politicians, and government. But there’s also a lot of very tedious bureaucratic stuff associated with the job, which I never got used to – to be honest. I’ve also met a lot of self-important people. Why are they important? They are important for being important. You can’t find out exactly what they did that got them to where they are. So I won’t miss that, I can tell you.”

Neither the “London establishment” nor the bureaucracy has been for him.

“It’s not me,” he admits.

Three years ago when he published his book, Gene Machine: The Race to Decipher the Secrets of the Ribosome, providing an insight into how he got his Nobel Prize, he had jokingly referred to two diseases – “pre-Nobelitis, for those who wait in vain for the prize year after year, and post-Nobelitis, evident in laureates who offer their opinions on anything and everything, regardless of their expertise”.

Now, he has identified another condition: “Establishmentitis”.

He explains: “I never felt that I fitted in with what I call the London establishment. That’s not my scene, although it was a great privilege. And it opened a window into a different world.

“And I certainly learned a huge amount that I didn’t know about – how things work? I don’t necessarily agree with a lot of it. But it was very interesting to do it for five years, but it’s not my world,” he adds.

Being the kind of down-to-earth person Venki is, there was little danger that the “glamour” of being Royal Society president would go to his head. He was remarkably candid: “It’s a bit fake, in the sense, a lot of the relations you have when you’re president of the Royal Society are what I call transactional. They’re not interested in you; they’re only interested in you because of the office you hold.

“And there’s a very big difference between that and some lifelong friends you have. You have to never forget that. Sometimes these relationships blossom into real friendships, but mostly not. Mostly, if you didn’t have that office, they wouldn’t give you the time of day. So you just have to not let the appearance of all these social interactions go to your head.

“Fundamentally, because I came from the US, I have more of a ‘Show me what you’ve done recently’ attitude. You should feel pleased about what you’ve done. Not about who you are which comes from what office you hold.”

He thinks the fact he was elected without having establishment connections sent a positive message to wider society.

“I’m not sure they would do that again, let me just put it that way, elect somebody as president who didn’t have any of this managerial and establishment and leadership experience.

“That was a bit of a gamble that they took when they elected me. Luckily, the Royal Society is a robust and very long lived organisation, so nobody can come and wreck it. I suppose you could say the same thing about the US presidency, although Trump seems to have done quite a lot of damage. But at least I hope I didn’t do that sort of damage. But I’m not sure that it’s likely to happen again.”

He found a bust of Srinivasa Ramanujan somewhere in the Royal Society building and elevated it to a prominent position behind his desk. Mindful Ramanujan faced resistance being elected to the Royal Society in 1918, Venki put some effort into promoting the movie on the Indian mathematical genius, The Man Who Knew Infinity, when it was released in 2015 – it starred Dev Patel in the lead role.

“That’s such a little thing,” says Venki. “It matters perhaps to people like us who are from India originally. (To us) Ramanujan represents a thing. It is a moment when Indians suddenly felt, ‘Oh, we’re not inferior, we could actually be just like these colonial masters. We’re just as good if we want to be.’ And it helped break a psychological barrier among Indians, having people like Ramanujan, or the early physicists, like C V Raman and (Satyendra Nath) Bose and (Meghnad) Saha. So in that sense, Ramanujan was a real pioneer. But to the average fellow, unless they’re mathematicians, it probably doesn’t mean much.”

He has found writing is something he really enjoys – and has been busy working on his new book, which has the working title, Is Death Necessary? Why and How We Age and Die.

Venki reveals what he has in mind: “It’ll cover a range of things from culture to sociology on how humans have dealt with the idea of death. The heart of the book will be about the biology of death, and then there’ll be quite a bit at the end about current efforts to somehow deal with death either from the point of view of therapeutics and with ageing. So it’s a very, very broad book. It won’t be a narrow book like the race for the structure of the ribosome. It will be quite a challenge to write. And that’s the thing I would most like to do.

“What medicine has done is allow more of us to reach a bigger fraction of our lifespan. Even if you went back 500 years, there were people who lived to be 100 years. It’s just very few of them reached that stage.

What’s changed is that instead of living on average for 40 or 45 years, now we’re living to be 80 or 85 or 90 years. But the question of whether we will live past 120 to become, say, 200 years old, is not at all clear.

“My view is that we should not be focused on extending lifespan. But rather we should be focused on how to make our old age as healthy and productive as possible.”

One thing no one can take away from Venki is that his name will remain for ever on the board that lists all those, including Isaac Newton, who have been president of the Royal Society.

A single taxi, with some boxes containing his few belongings – “I hardly had anything there” – sufficed to bring all his stuff back from his flat in London to his home in Cambridgeshire.

Venki still cycles everywhere – “I don’t have anything else. That is my only mode of transportation,” he says.

It is more than likely that even after the Royal Society, his words will continue to be heard.