THE story of Bengal farmers rising up against British colonial rule in the subcontinent is revisited in a new play, Indigo Giant, currently touring the UK.

In the late 19th century, vast swathes of the Bengali countryside were given over to the cultivation of the indigo plant as the British sought to meet the world’s insatiable desire for blue dye used in clothing.

However, the atrocities committed by British planters triggered an extraordinary revolution that changed Bengal.

Indigo Giant is based on Dinabandhu Mitra’s trail-blazing play Nil Darpan (The Indigo Planting Mirror), published in 1860 and made headlines at the time.It tells the story of the rebellion of Sadhu Charan, a life-loving indigo farmer in Kanaipur, Bengal, who is newly married to Kshetromani, a woman with visions of a beautiful future (both characters drawn from Mitra’s play).

At first, the couple lead an idyllic life. But the young newlyweds’ optimism begins to crumble when the new British planter, Rose, arrives and the malignancy of the indigo cultivation takes hold.

Leesa Gazi, co-founder and joint artistic director of Komola Collective, told Eastern Eye, it was her desire to shed light on a “forgotten moment” in British history that led to her producing Indigo Giant.

“In the 1800s, British indigo planters did terrible things to Bengali farmers (who were known as ryots) to grow indigo dye for the empire,” said Gazi.

“They beat them, raped them, tortured them and even killed them to take over their rice fields for growing indigo to satisfy the British empire’s appetite for indigo dye.

“This period ended in 1857, when the ryots rebelled in an extraordinary uprising and forced the planters out of Bengal.

“It is considered a significant moment in the struggle for independence.”

Mitra’s play shone a light on the cruel tactics of certain European indigo planters, which were further exposed by an official report of the 1861 Indigo Commission.

Ryots were forced to plant indigo, a crop that was in demand by the textile industry but deprived the land of nutrients.

Farmers were forced to take out loans and sell the crop to planters at fixed (low) prices, leading to a cycle of debt and economic dependence, that also saw the enforcement of violent means.

The play depicts the intimidation, exploitation, violence (including sexual assault) and lack of redress through the judicial system experienced by many in Bengal.

Gazi explained that she grew up reading about the neel bidroho (indigo revolt), but that she was shocked at how very few Britons knew about the episode in history.

“The legacy of the brutal history of indigo is still present in Bengal and in Bangladesh from stories passed on through the generations and is still very emotional,” she said.

“But the story has been buried in Britain. Sometimes, it’s not even perceived as British history, which I find astonishing.

“This play is not just a story for Bangladesh or people with Bengali heritage, it’s also a story for Britain.”

Gazi revealed that an event she attended about the Partition opened her eyes to how important it is to talk about the history of colonialism.

“We were talking about Partition and the south Asian students were very involved; they were emotional. But the white British students were quiet. I asked a professor from SOAS why they were quiet. She said something really interesting – that they didn’t feel it’s their space to talk about it, because it was not their history.

“That amazed me. How can this not be their history? We need to talk about these things; it’s our shared history. We need to confront it and learn from it together.”

The Komola Collective team carried out extensive research for the play. Playwright and co-producer Ben Musgrave grew up in Britain, India and Bangladesh, but he was not aware of the indigo revolt.

“He didn’t have any clue and that really hit him hard,” said Gazi.

“When he was commissioned to write this play, he went to Rangpur, Bangladesh, to do research and spoke to farmers and the artisans of indigo. They shared stories with him that they came to know from their ancestors.

“There is still an uncomfortable chill around the subject of indigo.”

Indigo Giant came about after a dialogue between British and Bangladeshi theatre makers after a Bengali version of the play toured Bangladesh in 2020. Some of the UK performances will be accompanied by a chorus of local community artists.“We are touring and engaging local south Asian performers with professional actors to deepen the impact of the production and also foster a meaningful exchange of skills, experiences and insights,” said Gazi.

She added the company has performed and done workshops with secondary school students and teachers to see how they “interpreted” the history and context of the play.

“The same kind of oppression is still going on today, but with a different kind of façade. When we see fast fashion, when we see the demand for cheap clothes and cheap labour, these garment factories are making people work in slave-like conditions – history is repeating itself.”

Gazi said the play is relevant given the debate about migration.

“When we talked about immigrants, we need to ask why are they here? They have a right to be here. If you want to ask these questions, then you must educate yourself on colonial history.”

Indigo Giant’s upcoming performances are at the Birmingham Rep, from Thursday (14) to Saturday (16); Soho Poly, London, next Tuesday (19) and Wednesday (20); Old Fire Station,Oxford next Friday (22) and Saturday (23); and Theatro Technis, Camden London April 4-6.

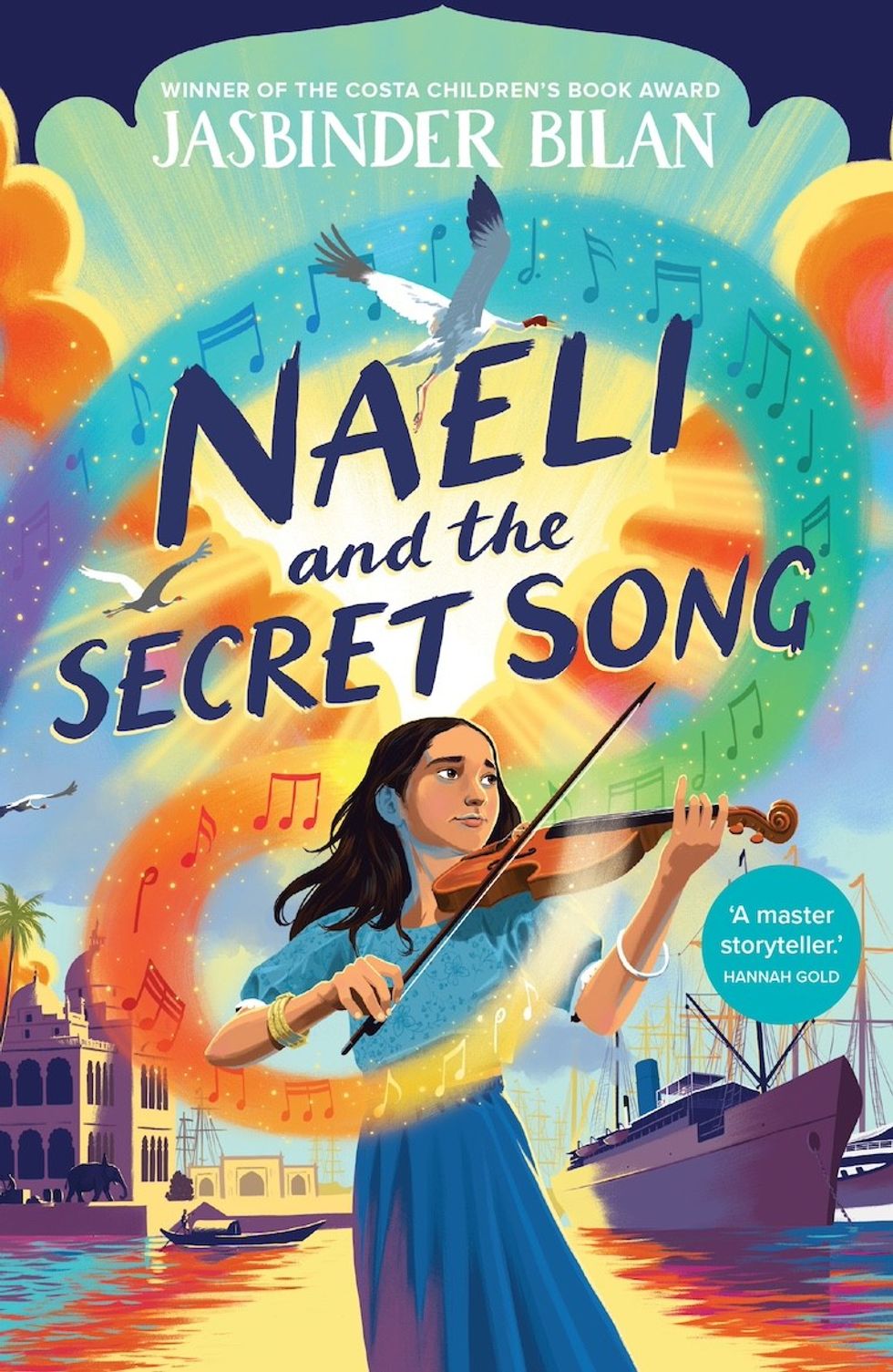

Naeli and the secret song

Naeli and the secret song

Jamie Lloyd’s Evita with Rachel Zegler set for Broadway after London triumphInstagram/

Jamie Lloyd’s Evita with Rachel Zegler set for Broadway after London triumphInstagram/

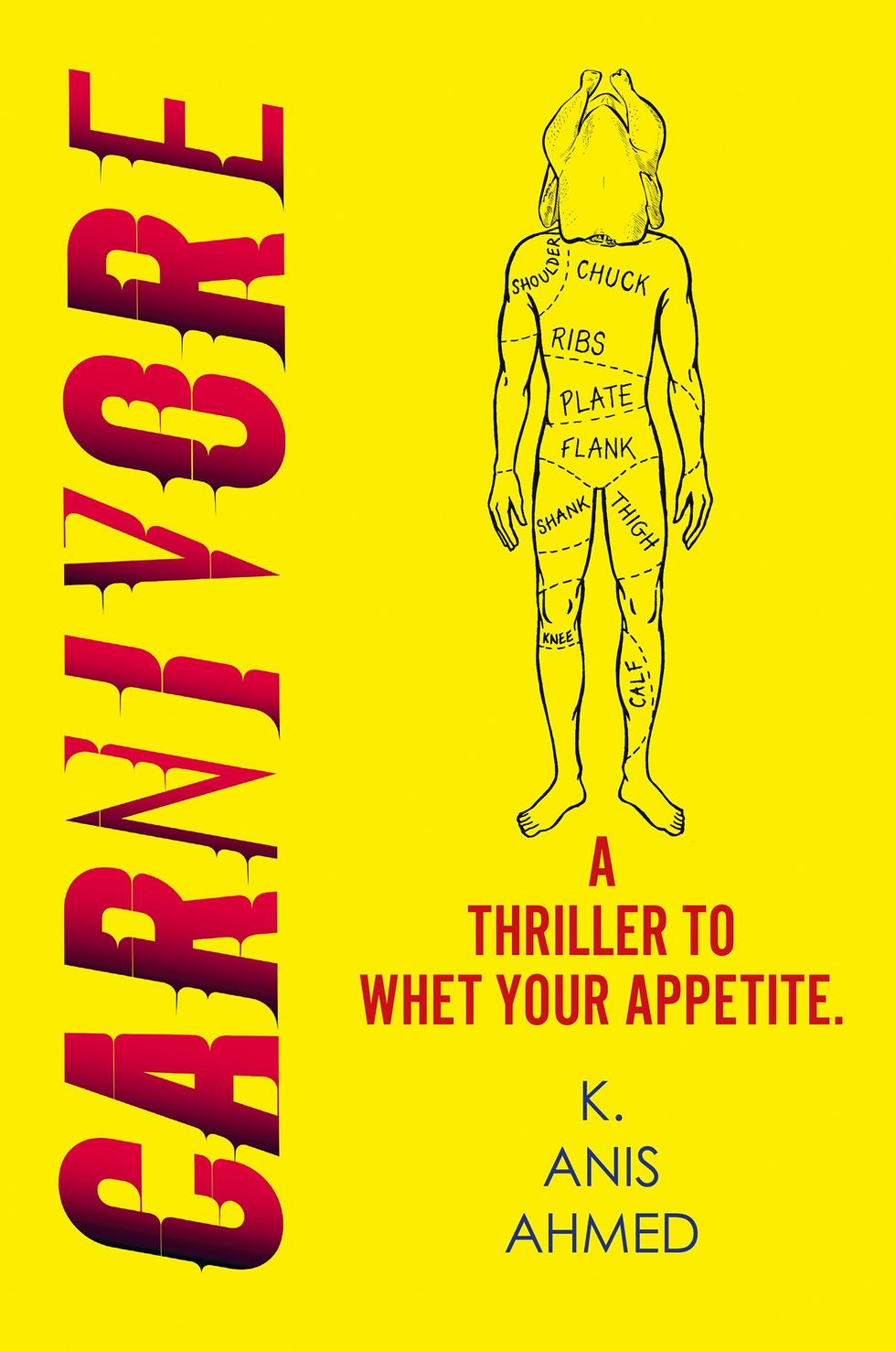

A compelling premise, layered and unpredictable charactersAMG

A compelling premise, layered and unpredictable charactersAMG Anyone who enjoys a gripping story with a diverse cast and unexpected twistsHarperFiction

Anyone who enjoys a gripping story with a diverse cast and unexpected twistsHarperFiction

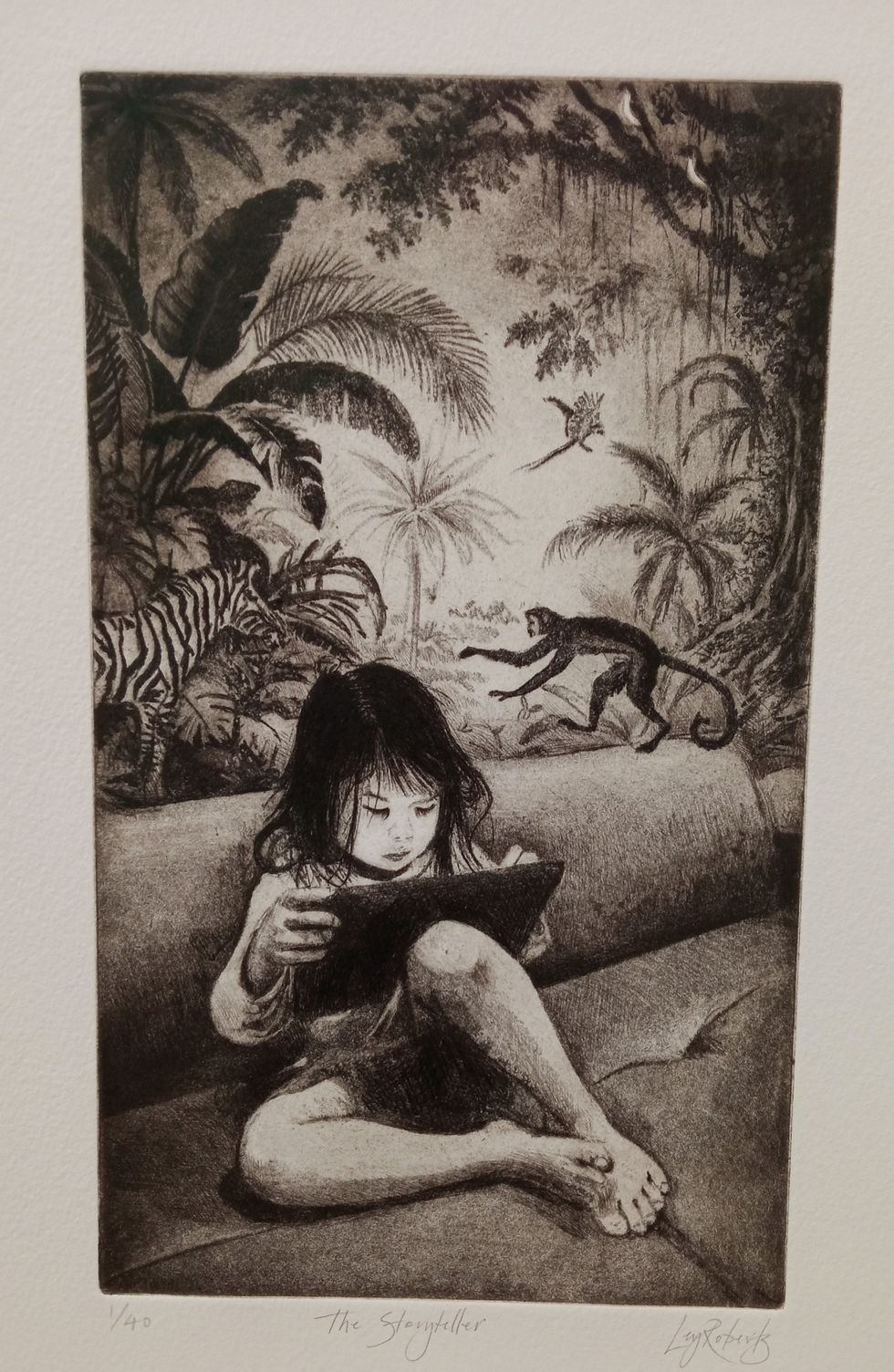

The Story Teller by Ley Roberts

The Story Teller by Ley Roberts Summer Exhibition coordinator Farshid Moussavi, with Royal Academy director of exhibitions Andrea Tarsia in the background

Summer Exhibition coordinator Farshid Moussavi, with Royal Academy director of exhibitions Andrea Tarsia in the background An installation by Ryan Gander

An installation by Ryan Gander A sectional model of DY Patil University Centre of Excellence, Mumbai, by Spencer de Grey

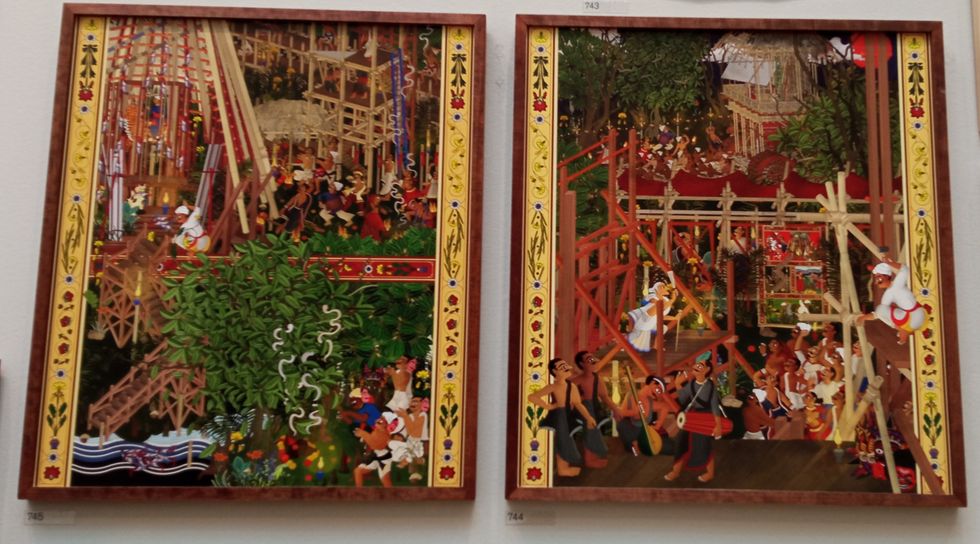

A sectional model of DY Patil University Centre of Excellence, Mumbai, by Spencer de Grey Rituals and Identity and Theatre of Resistance by Arinjoy Sen

Rituals and Identity and Theatre of Resistance by Arinjoy Sen