By Lord Tariq Ahmad

Minister for South Asia and the CommonwealthAS THE world confronts coronavirus, one of its greatest ever challenges, we need a united global effort to tackle this invisible killer.

Coronavirus has brought tragic loss of life and economic hardship to countries around the world. It also threatens to overwhelm health systems and allow other diseases to run rampant.

It is therefore hugely welcome that so many countries came together at the UK-hosted Global Vaccine Summit last week to replenish funding for Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

More than 60 countries participated in the summit hosted by prime minister Boris Johnson, including heads of state and heads of government. We heard speeches from India, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka.

The event aimed to raise $7.4 billion (£5.8bn) for the next five years, enabling Gavi to immunise 300 million people and save up to eight million lives, by vaccinating children against infectious diseases like measles, typhoid, diphtheria, and polio.

I am delighted to say that the summit, opened by Boris Johnson, surpassed its target, securing $8.8bn (£6.9bn) of donations. I am very grateful to every country that donated, as well as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and other philanthropists.

I am also delighted that India’s prime minister Narendra Modi participated directly and pledged $15 million (£11.8m) to the cause.

The UK has supported Gavi throughout its history and remains its biggest donor. Our pledge was for £330m a year over the next five years, a total of £1.65bn over the same period.

UK aid is also leading the push to develop a vaccine for coronavirus. Yet this is only part of the solution. Any successful vaccine also needs to be distributed – itself a major and complex task.

Gavi will have a key role in the future delivery of a coronavirus vaccine, making sure it is accessible and affordable to everyone who needs it.

Work on this has started at pace, with AstraZeneca, Gavi, and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, which UK aid supports, signing a $750m (£591m) agreement at the summit to support the manufacturing, procurement and distribution of 300 million doses of Oxford University’s coronavirus vaccine, which is currently in development. UK scientific expertise is at the heart of this global call to action.

In addition, I’m pleased that AstraZeneca reached a licensing agreement with Serum Institute of India to supply one billion doses for low-and-middle-income countries, with a commitment to provide 400 million before the end of 2020. This is vital to ensure equitable access to the vaccine.

Gavi has a superb track record in delivering vaccinations to children in the poorest countries and I am proud of the UK’s relationship with Gavi. People who are vaccinated protect themselves and others by lowering the spread and risk of infection.

The group has immunised more than 760 million children and saved more than 13 million lives since it was set up in 2000.

But right now, coronavirus is disrupting many vaccination programmes. The World Health Organization estimates that 80 million children aged under one have had routine immunisation affected.

Gavi’s role has never been more important. And there are four important ways in which it strengthens and supports developing countries by protecting their populations from deadly diseases.

First, Gavi has helped to drive down prices and incentivise innovation. Between 2015 and 2018, its market-shaping efforts to make life-saving vaccines more accessible and affordable saw a 21 per cent price reduction for fully immunising a child against a range of common diseases, including diphtheria, tetanus, hepatitis B and rotavirus.

And last November, supported by Gavi, Pakistan became the first country in the world to introduce a new improved typhoid vaccine, the first of its kind which can be given to children as young as six months old and provides longer term protection.

This year, Gavi has also launched a new measles vaccination drive in a number of countries, which included targeting 15.5 million people in Bangladesh and three million in Nepal.

Second, Gavi-funded vaccines have also been proven to help alleviate poverty. Oxford University found that immunisation against common causes of pneumonia in Nepal was saving poor urban families from destitution, as the cost of hospital fees often exceeded a family’s monthly income.

Third, Gavi support has also allowed countries to begin to fund their domestic vaccination programmes. Sri Lanka now runs its own programme.

And finally, one of the most significant measures of success is when recipient countries become donors to Gavi. In 2014 India became the first recipient country to donate to Gavi.

However, there is no room for complacency. Diseases do not respect borders, as Covid-19 demonstrates, and no one is safe until we are all safe.

That’s why the Global Vaccine Summit was so significant. It was a wonderful example of what we can all accomplish when the world takes action together. It’s the interdependency of humanity and our collaborative working which will ultimately help us defeat this global pandemic.

Nigel Farage

Nigel Farage Rupert LoweGetty Images

Rupert LoweGetty Images

Rajan offers the pind daan in honour of his father and ancestors

Rajan offers the pind daan in honour of his father and ancestors

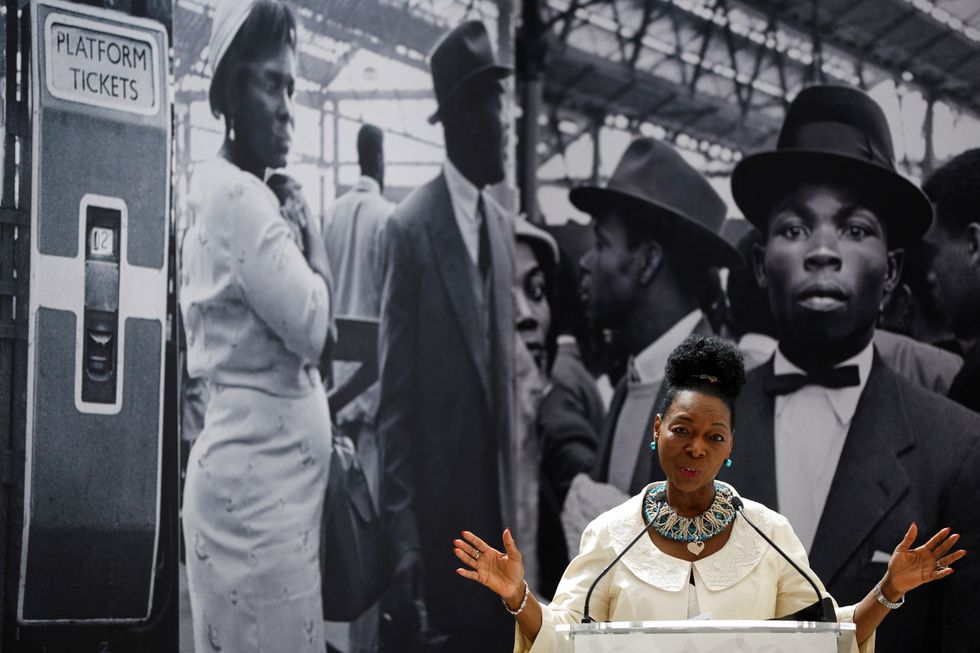

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)