THE 1990s were a time of hope in India.

One of my jobs at the Daily Telegraph was to travel regularly to India and do surveys of the Indian economy.

While I would do the journalistic interviews, an accompanying colleague from advertising would try to persuade captains of industry to take out ads in the paper. I still have his rate card: £36,500 for a full-page ad; £45,000 if it was in colour. One special report carried so much advertising, I reckoned the paper made £150,000 from the venture.

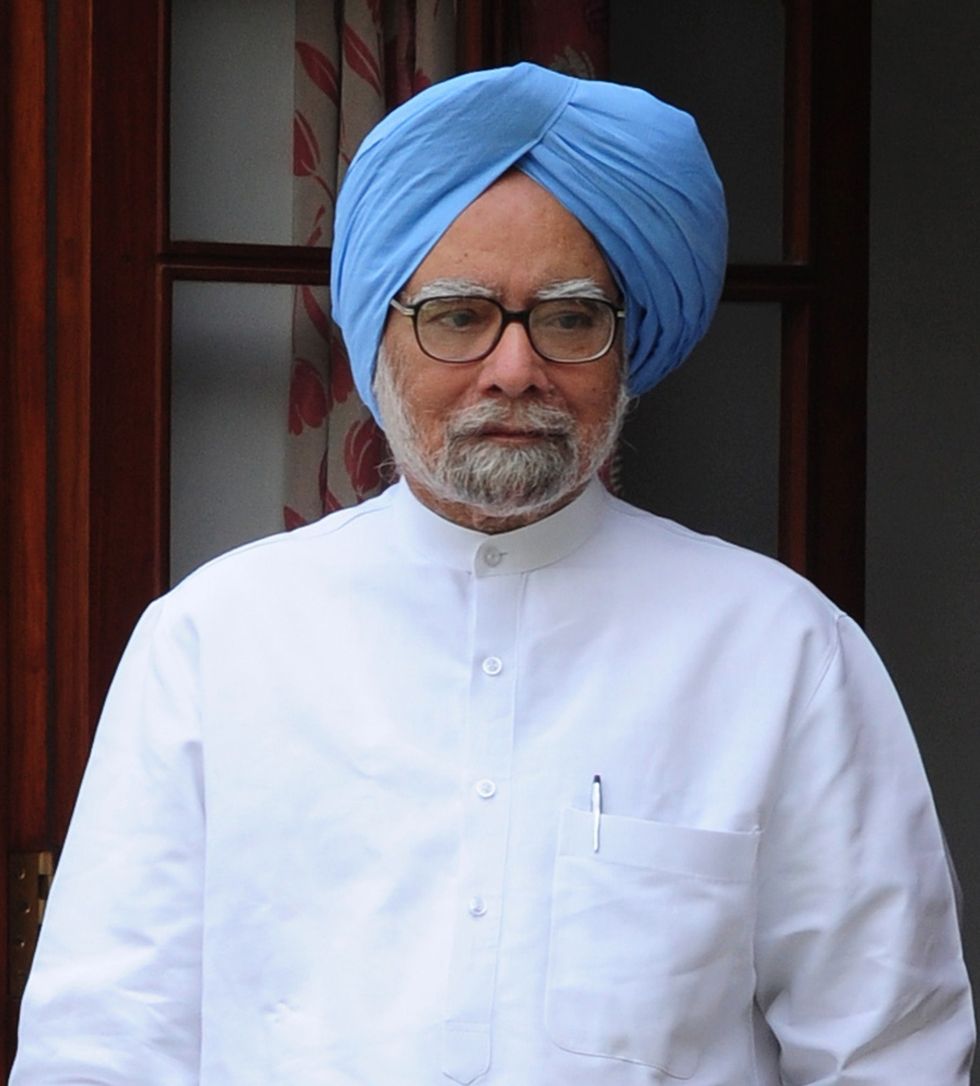

One of the trips was in July 1995 when PV Narasimha Rao of the Congress Party was the prime minister. He had started the process of liberalisation in 1991, when he had opened India up to the challenges of the global economy. He had appointed Dr Manmohan Singh, an Oxbridge educated academic and former

governor of the Reserve Bank of India, as his finance minister. Singh became prime minister from 2004-2009 and served a second term from 2009-2014, before Narendra Modi of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came to power that year.

In 1995, Dileep Padgaonkar, former editor of the Times of India, told me: “Economic liberalisation is doing extraordinary things to Indian society. Words such as money and profit are no longer derogatory. For the first time, I feel optimistic about India.”

Tarun Das, director general of the Confederation of Indian Industry – India’s equivalent of the Confederation of British Industry – predicted: “India will definitely emerge as an economic superpower.”

I went to Bangalore, capital of Karnataka, which was even then being hailed as the “Silicon Valley of India”. It was the city of “booze and bleepers”. Bangalore had 150 very noisy pubs. Business folk wore bleepers to show how important they were – mobile phones, which would transform India, were a thing of the future. I stayed at the Windsor Manor, where I was allocated a personal Jeeves.

So far as the British media is concerned, the perception of India has changed over the past 75 years from a third world country to an economic powerhouse with a large middle class population. That is why post Brexit, the UK is keen to negotiate a Free Trade Agreement with India. On his trip to India in April this year, prime minister Boris Johnson expressed the hope that an agreement would be ready to sign “by Diwali”.

The way British newspapers once dealt with India was very different.

At the Daily Telegraph, for example, we would routinely report the “immigration figures” issued by the Home Office. If “New Commonwealth” immigration, notably from India and Pakistan, was down, that was regarded as a positive development. In 1979, some Indian women coming as intended brides were subjected to “virginity tests” by male immigration officers at Heathrow.

By and by, the economic story from India became more important. The business pages of newspapers began taking more of an interest in India. Looking back on it now, there was another important development, but this time in the UK.

This was in 1990. Philip Beresford, who was compiling the Rich List for the Sunday Times, came across a couple of Asian names. Did I know them? Could I suggest a couple more? I said I could offer another 50, possibly even 100.

In the event, the first Asian Rich List was published in Management Today, which Beresford took over as editor. I took the story to the Daily Telegraph, which I had rejoined. It ran in the Telegraph Colour Magazine with a cover picture of Naresh Patel, of Colorama, standing in front of a Porsche. The headline was: “My other car is a Rolls.”

The piece introduced characters then unknown – such as Srichand Hinduja and Swraj Paul – but who have subsequently become familiar ones.

What the Asian Rich List did was dispel the notion that Indians had emigrated to Britain to live as parasites on state handouts. On the contrary, they were creating jobs for ordinary people.

British Indian society was also changing. At a Sunday Telegraph news conference on a Tuesday, Charles Moore, the editor, said he thought I looked a bit tired.

A colleague cut in disloyally: “That’s because he’s always going to parties.”

It ended with Charles ordering me to do a piece on the glamorous Friday night parties that Ramola Bachchan (married to Amitabh Bachchan’s younger brother, Ajitabh Bachchan) held at her home – 2 Frognal – in the heart of Hampstead village in north London.

Ramola’s tables offered a choice of Indian, Italian and Thai food. And there was champagne. Hers was the best party in town where one could meet anyone who was anyone in the new India. Anil Agarwal (of Vedanta) was a regular guest. On another occasion, I remember Imran Khan, ever the party boy, dropping in. Ramola’s parties reflected what was happening in the resurgent new India.

In the early years of independence, the Indian economy was protectionist, but the country did build up its industrial infrastructure, which made Rao and Singh’s economic reforms possible. Rajiv Gandhi, who had taken over as prime minister after the assassination of his mother, Indira Gandhi, in 1984, was a young man with a progressive vision of the future. He certainly believed in computers.

I saw him in 1986 when he said he wanted India to be an economic superpower by the end of the century.

My first survey of the Indian economy was in 1993 when John Major was the chief guest at the Republic Day celebrations on January 26. Television was starting to drive middle class and even rural aspirations. Adi Godrej, managing director of Godrej Soaps, said increasing soap sales were an indicator of social change. “A village woman will not spend 93p on a bottle of shampoo, but she will buy a 2p sachet,” he observed.

In 1994, I spoke to Shoba (now Shobaa) De, author of such racy novels as Starry Nights and Socialite Evenings. “Almost every Christmas or New year’s eve party this year will be black tie,” she said.

In 2006, I interviewed Manmohan Singh who said: “Today all sections of our economy are open for foreign investment. Our effort is to ensure that India has a world class infrastructure. That includes ports, airports, roads, the transport services, a lot more investment in the power sector and other related energy systems. These are our highest priorities.”

The prime minister added: “We also want our financial services system to be liberalised and expanded. All these are areas in which I believe the United Kingdom has distinct capabilities which can be harnessed to our mutual advantage.”

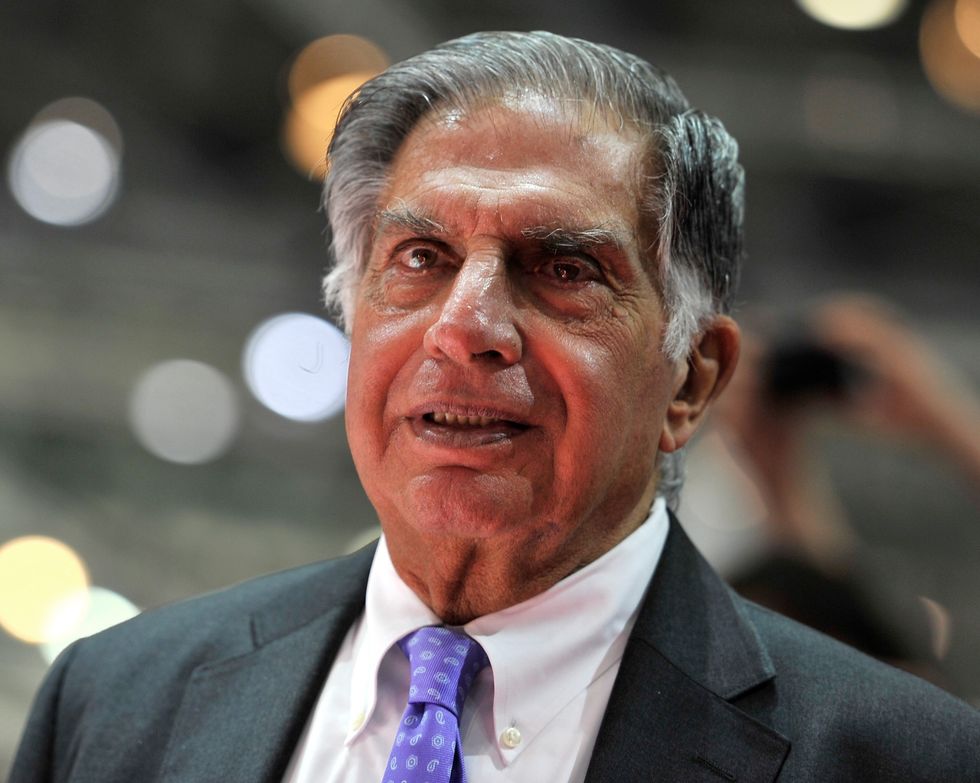

I also met Ratan Tata, chairman of the Tata Group at his office, Bombay House, in Mumbai. He did not tell me he was poised to make a bid for Jaguar Land Rover and Corus Steel, but he did say: “Protection has been India’s worst enemy but, thanks to globalisation, 25-30 per cent of our revenues comes from overseas business.”

In 2010, I was in Delhi for David Cameron’s first visit as prime minister. He had gone as opposition leader in 2006 and would visit twice more as prime minister and was always accompanied by large trade delegations.

One shouldn’t be boastful. India is still not an economic superpower. It has a long way to go before it catches up with China. But in the last 75 years, it has come a long way. Despite all the problems the world is facing after the pandemic, one can be reasonably optimistic about the Indian economy. Its diversity should be a source of strength.

The circular structure inspired by jali screens in India

The circular structure inspired by jali screens in India Sophie, Duchess of Edinburgh, at the garden

Sophie, Duchess of Edinburgh, at the garden The couple display their medals

The couple display their medals