by MUSTAFA FIELD MBE

MODERN Britain is as diverse as it has ever been.

People of over 200 different nationalities now call the UK home, and more than 300 different languages are spoken in British schools. Added to this rich cauldron of diversity is a host of religions, denominations and world views that stand outside the nine main faith traditions in the UK.

As such, the findings recently released by the Commission on Religious Education (RE) – that around a third of secondary schools do not offer RE as an option at GCSE or that less than a quarter of schools teach RE during the first three years of senior school – was hard to stomach.

As a director of Faiths Forum for London, an umbrella organisation that represents nine faiths across our capital, I would welcome any opportunity to extend the curriculum, not least if it enhances the overall learning of our children and better prepares them for the realities of modern Britain.

Religion has become a hot topic in recent years and it often dominates the opinion sections of our newspapers. Some faiths in particular – mine included – have been increasingly put under the editorial microscope and are sometimes portrayed unfairly. With such an emphasis placed on religion in wider society, it is alarming that teaching of RE has been found to not just be inadequate but non-existent in many schools across the UK.

I believe that education is as much about knowledge as it is understanding: it encourages critical, reflective thinking in everyday life. I know many people who describe their relationship with religion as being more to do with ethical cultivation than spiritual fulfilment – they live in compliance with the doctrinal positions of Christianity or Islam, for example, but do not pray routinely or regularly engage in religious text readings.

While the religious make-up of Britain is plural and diverse, a recent survey by British Social Attitudes in 2017 found that 70 per cent of people aged 18-24 said they had no religion, an increase from 56 per cent in 2002. This is a reality of modern Britain, but it shouldn’t merit such a shift in curriculum.

RE is different from religious instruction, after all. It would equip our children with the critical skills to better navigate the complex issues we have increasingly found attached to religion, and also help them to immunise themselves from the fallacious and harmful narratives pushed by extremist groups – both Daesh-inspired and far-right – similarly oblivious to the realities of my religion of choice, Islam.

Broadening the curriculum will encourage children to deal positively with controversial issues, think critically about strongly held differences of belief and challenge stereotypes they might encounter later in life. It could also allow for stronger friendships to form across religious divides and develop children’s respect and empathy for others at an early age. Understanding of differences is fundamental to a successful and diverse society. An education system that highlights and celebrates the positive contributions made by people of all faiths and none can truly capture the collective identity of modern Britain, which stands against ideologies of division and violence.

One of the greatest privileges of the democratic society we live in is freedom of choice – choice of religion, choice of politics, choice of what we eat for breakfast. Sometimes those freedoms are taken for granted. If we remove another privilege available to us, a comprehensive education, then fear of the unknown and prejudice could set in – and that’s the lifeblood of division.

Every pupil should have access to the subject. Whether they choose to take it further educationally or spiritually is a decision that they – and they alone – are entitled to make, but schools have a responsibility to at least provide this space for learning in their formative years.

So long as division and prejudice exists, education must be considered the antidote. Similarly, all views must be examined if schooling is to be meaningful. Changes which acknowledge that – such as those outlined by the Commission on Religious Education – should be welcomed by anyone who believes in education more generally.

Young people are growing up in an ever-shifting cultural landscape and face serious challenges to their identity, spiritual persuasions and ideological commitments. With society changing so much over the years, it’s time RE caught up with it.

Mustafa Field is a director of Faiths Forum for London. Twitter: @mustafafield

Nigel Farage

Nigel Farage Rupert LoweGetty Images

Rupert LoweGetty Images

Rajan offers the pind daan in honour of his father and ancestors

Rajan offers the pind daan in honour of his father and ancestors

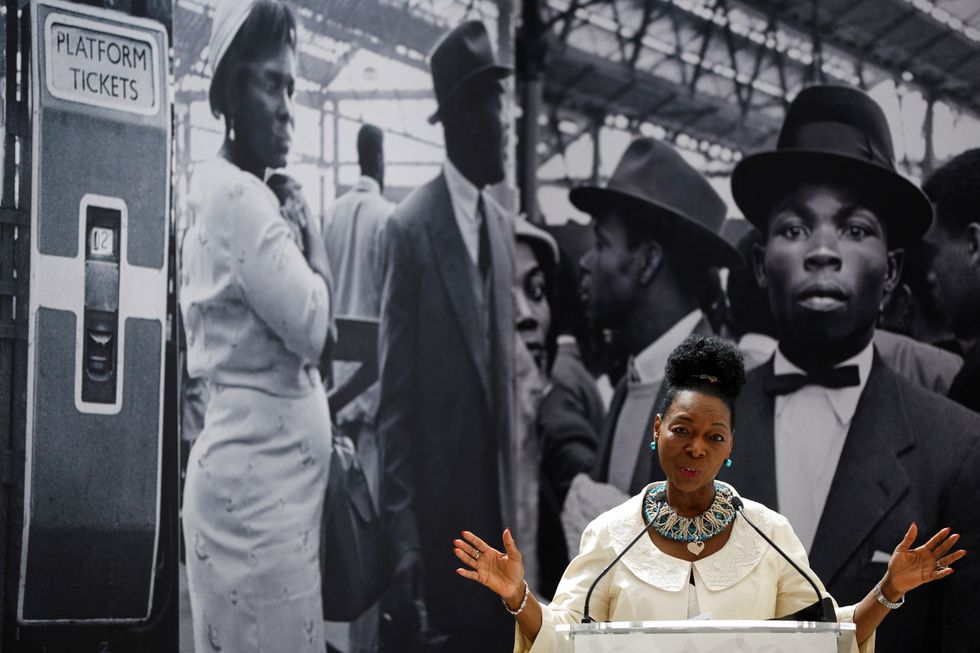

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’

Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’ Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’

Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’ Mahira Khan

Mahira Khan ‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience

‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’

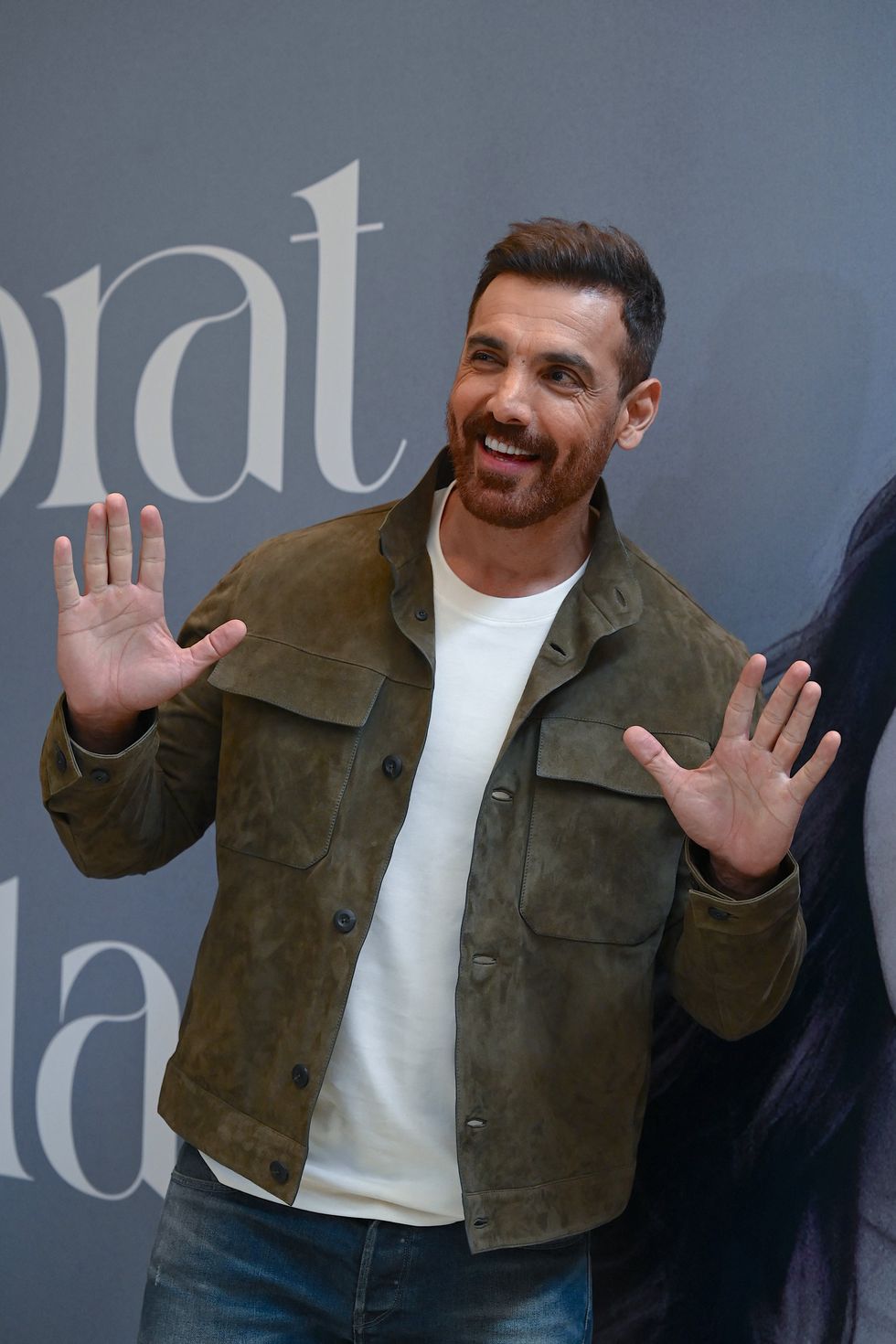

Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’  John Abraham

John Abraham Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal

Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal  Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut

Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut Sana Yousuf

Sana Yousuf