When a major theatre production is announced, tickets often become hard to get as they sell out months in advance. That has not been the case with Come Fall in Love – the much-hyped stage musical inspired by the 1995 Bollywood classic Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge. The newly premiered show, running at Manchester Opera House from Thursday (29) to June 21, has struggled to sell seats, despite advance bookings opening months ago.

Swathes of empty seats remain available across all price bands, and the upper gallery appears to have been closed off entirely due to poor demand. It is a clear sign that this cross-cultural adaptation has failed to connect with audiences. The warning signs were visible from the outset, with multiple red flags suggesting it would become an expensive failure.

The musical had already stumbled in the United States, where critics were scathing and audiences largely indifferent. Originally conceived as a potential Broadway production, its world premiere in San Diego received a lukewarm response, and the dream of a New York transfer quietly disappeared. That should have been a wake-up call.

Instead, the producers doubled down and brought the flawed show to the UK, bizarrely choosing Manchester as the launch venue.

Common sense should have made clear this was a strategic error. Anyone familiar with the UK’s live entertainment scene knows that most major Indian productions regularly bypass Manchester. This is largely due to a local audience unwilling to pay high ticket prices, making such shows commercially unviable.

The city also lacks a strong track record for large-scale South Asian theatre hits. The producers of Come Fall in Love are now learning that the hard way.

The situation has been worsened by a misguided attempt to appeal to non-Asian audiences. The character of Raj – immortalised by Shah Rukh Khan – has been rewritten as a white man named ‘Roger’.

This single creative decision strips the story of its charm, cultural specificity and emotional resonance. The change alienates core Bollywood fans and does little to attract new ones.

Authenticity matters – especially when adapting one of Indian cinema’s most beloved love stories.

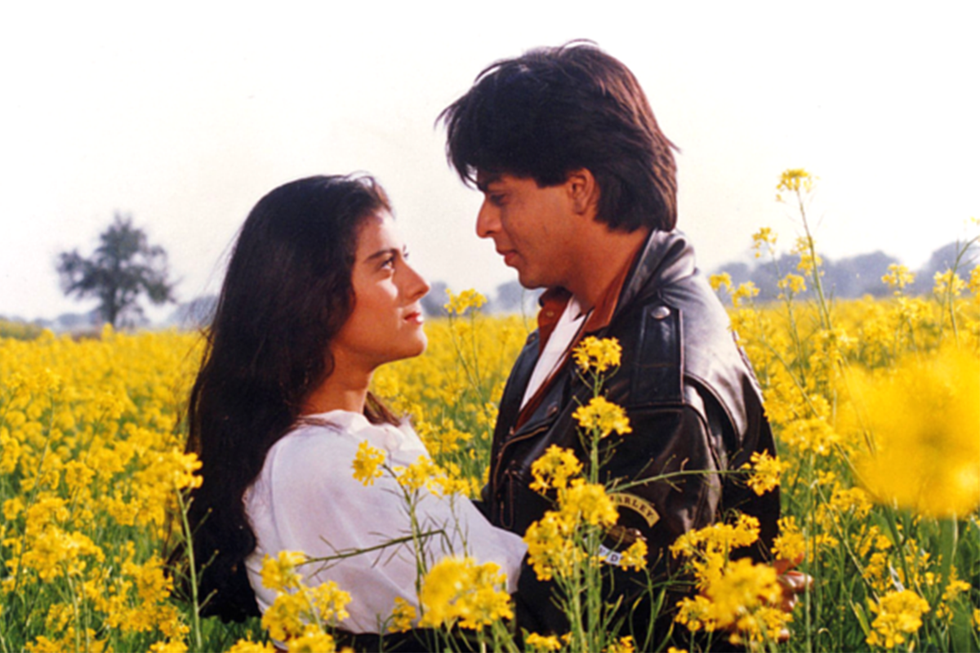

Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge is not just any film. It’s iconic and a cultural landmark. Referred to as DDLJ, it redefined the genre in the 1990s, launched a thousand love stories, and ran continuously at Mumbai’s Maratha Mandir for over two decades.

It captured the diaspora experience while remaining deeply rooted in Indian tradition – something this musical seems to have misunderstood entirely.

Ironically, a stage version could have succeeded if it had embraced the original’s identity and spirit – as Bombay Dreams did in 2002, bringing unapologetic Indian flair to the West End.

Instead, Come Fall in Love dilutes the very qualities that made the film special.

In recent months, the producers have tried nearly everything to generate interest, including releasing the title track. Composers Vishal-Shekhar have done the media rounds, and even Shah Rukh Khan visited rehearsals to lend star power.

But none of it has been enough to salvage a production that feels like a sinking ship with gaping holes.

The sad truth is Come Fall in Love may have fared better in London – a city with a larger South Asian population, a more vibrant theatre culture, significant tourist traffic and, crucially, audiences with greater disposable income.

Instead, it finds itself in a city that, while culturally rich, has shown little appetite for expensive touring musicals of this kind.

Even if ticket prices are slashed at this stage, too many mistakes have already been made.

With reviews likely to be negative, things could go from bad to worse for Come Fall in Love, which is looking more like ‘come fall flat’.

Come Fall in Love runs at Opera House in Manchester until June 21. www.comefallinlovemusical.com.