UK BROADCASTERS do not want to make programmes on the Bengal Famine of 1943 for fear it might tarnish Sir Winston Churchill’s reputation, a British Asian museum curator has told Eastern Eye.

Sona Datta said that Kavita Puri had made a “remarkable breakthrough” by getting BBC Radio 4 to commission Three Million, her series on the famine.

But this was more an exception, Datta indicated.

Churchill’s critics – especially among Indians, such as the MP and author Shashi Tharoor – allege that Britain’s wartime prime minister could have done much more to help the victims of the famine. Others argue Churchill resisted Indian independence and often used racist language, but was not blame for the effects of the famine.

Datta made her comments as an exhibition on the famine, Hunger Burns, opened in the heart of the Bangladesh community in Tower Hamlets in the East End of London.

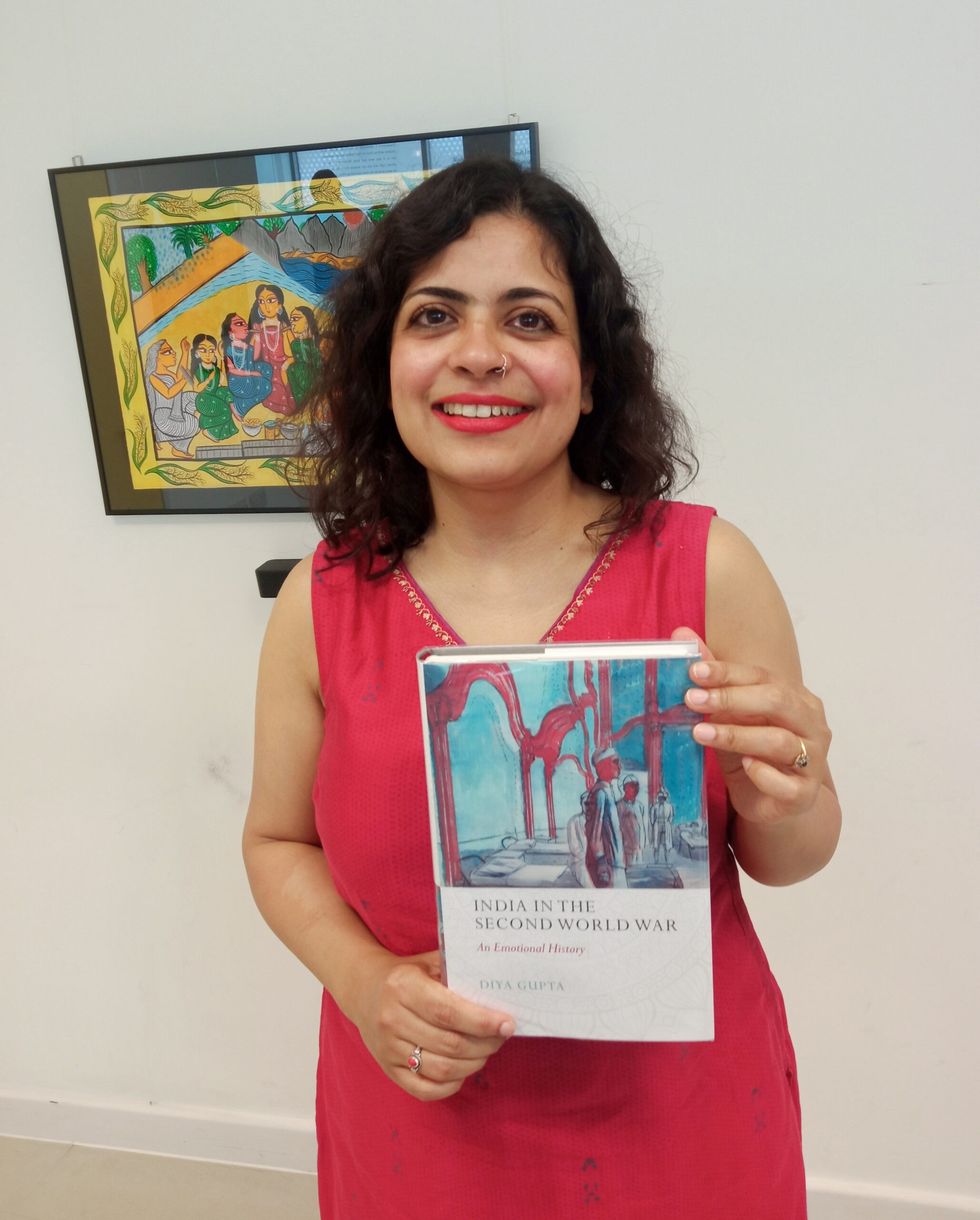

Material for the exhibition, which will run until August in Watney Market Library in the Commercial Road, is drawn from India in the Second World War: An Emotional History, by cultural historian Diya Gupta.

She makes use of letters between Indian soldiers fighting for Britain in the Second World War and their families back in India.

Extracts from the censored letters are dotted around the floor and walls of the library. The exhibition design was undertaken by the Berlin based artist, Sujatro Ghosh, while Eeshita Azad read a poem she had written for the occasion.

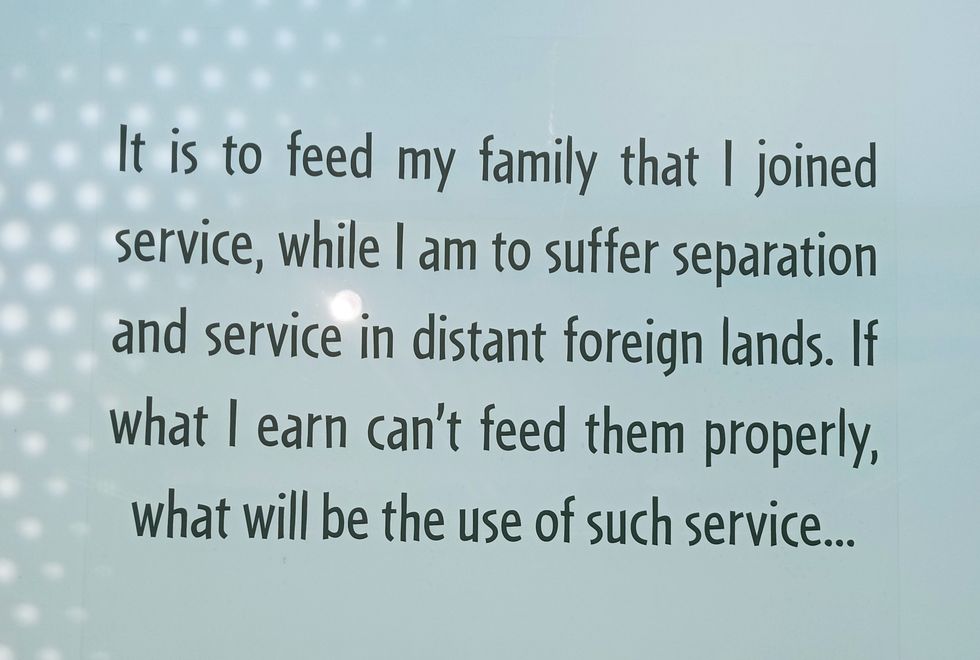

One letter, probably written by a soldier, says: “It is to feed my family that I joined service, while I am to suffer separation and service in distant foreign lands. If what I earn can’t feed them properly, what will be the use of such service...”

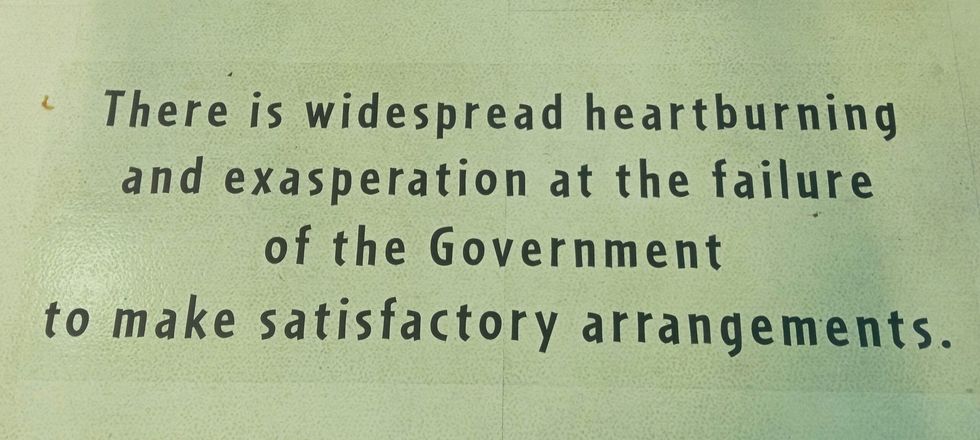

Another states: “There is widespread heartburning and exasperation at the failure of the government to make satisfactory arrangements.”

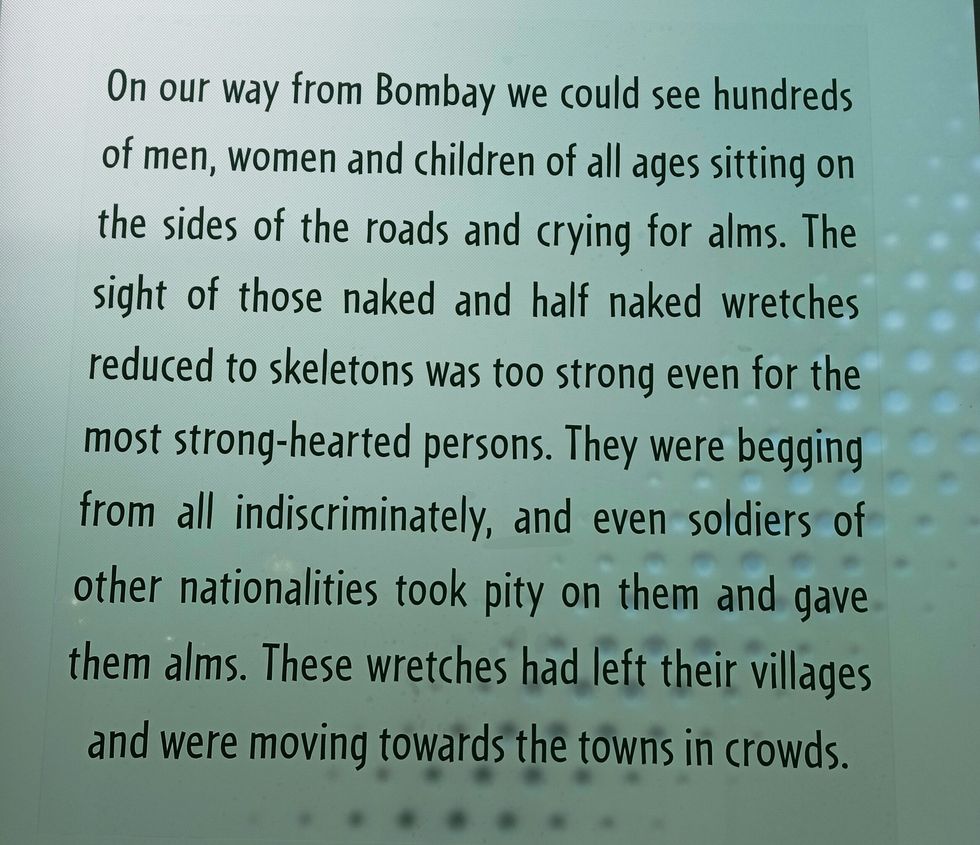

A third letter reflects the writer’s anguish: “On our way from Bombay we could see hundreds of men, women and children of all ages sitting on the sides of the roads and crying for alms. The sight of those naked and half-naked wretches reduced to skeletons was too strong even for the most strong-hearted persons.”

At partition in 1947, West Bengal, with a mainly Hindu population, went to India, while the eastern part of the province, where Muslims were more numerous, became East Pakistan. This broke away from West Pakistan after the civil war of 1971 and became today’s Bangladesh. But in 1943, the famine did not discriminate between Hindus and Muslim.

Datta, who worked for the British Museum before becoming head of South Asian art at the Peabody Essex Museum in Massachusetts, said: “Even as a seasoned museum curator, it was very hard to sell the unpalatable taste of famine to English institutions. Add to that the perceived threat to Churchill, which placed considerable barriers before us. But it was also really important for us to embed this project in the heart of the Bengali community.”

She declared: “In 1943, three million people perished needlessly. Rice harvest that had sustained populations for centuries, were, in part, appropriated by the British for the war effort. The famine was not a consequence of a lack of food, but a product of unchecked inflation, hoarding, and resource extraction. And it led to the catastrophic loss of life, and also to an occidental projection that this is a region that can’t care for itself or provide for itself. But, in fact, this was a result of catastrophic colonial mismanagement.” She said the exhibition was trying to give speech to previously unheard voices: “This project is really a recognition of the shame and generational trauma suffered by women in particular, when we cannot feed our families. Two and-a-half million people fought for the British during World War Two. And while they were fighting the good war at the far frontiers in Europe and the Middle East, their loved ones were dying of starvation at home. It’s particularly poignant today because another famine is unfolding in the Middle East. And there is, of course, a rather heavy Israeli elephant in the room.”

Later, in a separate interview with Eastern Eye, Datta said: “I’ve worked in big museums. South Asia is packaged in a particular way for a western audience. We love shows about Rajput paintings and maharajahs, but on famine there was no traction.”

She revealed: “We pitched to the BBC and Channel Four for a series on the famine. This was in 2022, as we were coming up to the 80th anniversary in 2023. But nobody would go near it. There was so much anxiety around Churchill in the upper echelons in this country.

“It’s an incredible breakthrough that Kavita Puri managed to make her Radio 4 series. Now that people are hearing it, it is really resonating with people. It’s such a human story. It’s part of our war history. Churchill got us through the war, but at what cost at the far ends of empire.”

Datta graduated from King’s College, Cambridge University where she was awarded the Rylands Prize for Excellence in the History of Art and the James Prize for Creative Writing. She said: “Those kinds of complexities of decolonisation are not really understood in our public institutions. I’ve long maintained that post-colonial studies are very robust in academia. But it doesn’t translate into meaningful policy or public programming in our cultural institutions. And that is the juncture at which you get the chance to touch ordinary people and give them an unexpected cultural encounter and make them think in a different way. That’s why I work in museums.”

Gupta’s book begins with two evocative black and white photographs taken by Sunil Janah.

The author writes: “A serpentine row of women, some holding on to their children, horizontally bisects the photograph. Where does the queue begin; where will it end? We do not know: the women and children spill over the frame of the camera, as though uncontainable within a single image.”

The second photograph is even more heartrending for it shows starving orphans waiting in the sun.

Gupta, lecturer in public history at City, University of London, told Eastern Eye that the original letters, which were usually written in Indian languages – they had to be translated into English for the censor – have all vanished. Only the translations remain in the archives.

She said: “I call my book ‘an emotional history’, because I was always interested in the subjectivities of people as they endure and live through or don’t live through, in some cases, something as traumatic as a world war. I wasn’t a scholar of food or famine. But I came to famine through war. And as I studied the Second World War in India, I realised I couldn’t but talk about famine. It was a product of this war. And for me, it was a form of violence inflicted on civilian bodies through war. But instead of a bomb, instead of a bullet, this was hunger. It was slow, and it burnt.”

Hunger Burns runs until August 2024 at Idea Store Watney Market, 260 Commercial Road, London E1 2FB

(Photo credit: PTI)

(Photo credit: PTI)

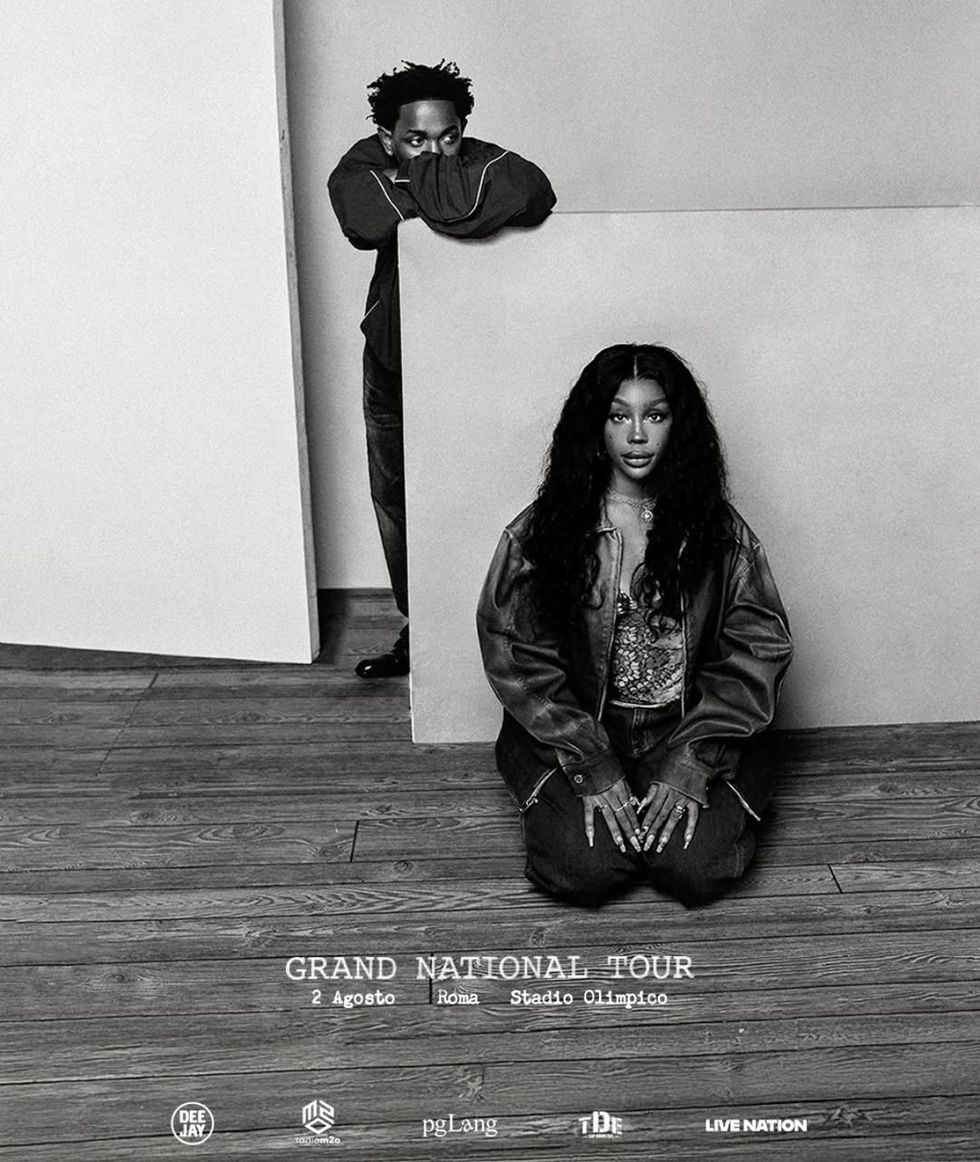

Kendrick Lamar and SZA commands the stage at Villa Park during his explosive opening setInstagram/

Kendrick Lamar and SZA commands the stage at Villa Park during his explosive opening setInstagram/