Highlights:

- Aanand L Rai has been testing AI-driven tools in editing, dubbing, colour grading, and alternate storytelling.

- A re-edited Tamil version of Raanjhanaa (Ambikapathy) features an AI-generated “happy” ending, without the director’s consent.

- Rai calls the unauthorised edit a violation of creative trust, sparking a wider debate about AI’s role in Indian cinema.

- He proposes contract reforms to ensure mandatory consent for AI-assisted modifications in films.

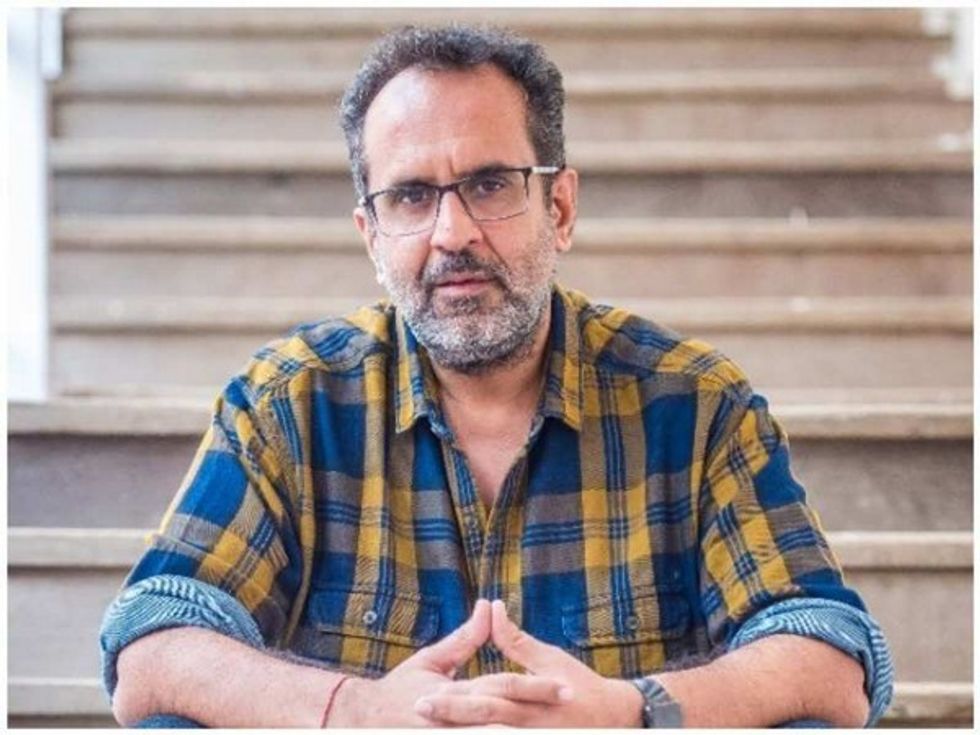

As artificial intelligence accelerates its entry into global filmmaking, Bollywood director Aanand L Rai finds himself both a pioneer and a protester. In recent months, the Tanu Weds Manu and Raanjhanaa director has been quietly experimenting with AI tools, from storyboarding and colour grading to dialogue enhancement and alternate endings. But when one of those experiments was co-opted and released without his consent, the results became a flashpoint for the Indian film industry.

Rai is now at the centre of a national debate after Eros International announced the 1 August release of Ambikapathy, a Tamil-dubbed, AI-modified version of Raanjhanaa (2013). The new cut, which features a radically different ending in which protagonist Kundan survives, was created using generative AI tools but released without input or approval from Rai or his team.

Rewriting Raanjhanaa: Innovation or interference?

Originally, Raanjhanaa ended with Kundan, played by Dhanush, dying in Varanasi after a life marked by unrequited love and spiritual redemption. The AI-generated Ambikapathy, however, flips the tone, preserving Kundan’s life and offering what Eros calls a “respectful reinterpretation.”

For Rai, the change is anything but respectful. “Machines can’t create films. The tragedy was part of Raanjhanaa’s DNA. You can’t just rewrite its soul,” he said in an interview.

While Eros CEO Pradeep Dwivedi defended the move as a legal and creative right, part of the company’s strategy to revisit its catalogue through AI-driven narrative experiments, Rai views the release as a breach of artistic trust. “Even if I’ve waived certain rights contractually, there must be a moral line,” he said. He has asked to have his name removed from the new version and is preparing a formal complaint to industry bodies.

Rai’s controlled AI trials: From colour grading to alternate endings

Ironically, Rai’s criticism of the AI-altered Raanjhanaa comes even as he explores AI’s possibilities in his own projects, on his own terms.

Behind closed doors, Rai has been running structured experiments with AI-assisted filmmaking. One such test involved generating a happier alternate ending for Raanjhanaa to study how audiences respond to different narrative resolutions. “It was never meant for release. It was an academic what-if,” says a close aide.

He has also been testing machine-learning tools for automated colour grading, emotional tone-mapping in dialogue delivery, and even generative storyboarding for his upcoming film Tere Ishq Mein. In post-production on that film, Rai is said to be using neural network software to optimise mood lighting and scene pacing.

Next on his roadmap: experimenting with AI-driven dubbing across regional Indian languages and holding creative workshops for crew and cast to discuss the ethics and potentials of AI filmmaking.

Why consent is non-negotiable for AI filmmaking

While Rai acknowledges that AI can aid the filmmaking process, speeding up workflows and assisting in visualisation, he draws a sharp line at creative autonomy. “AI should be a tool, not a storyteller. The final voice must always be human,” he insists.

He is now working with lawyers and fellow filmmakers to develop contract templates that include explicit consent clauses for AI-based changes. These would protect directors and writers from having their work altered posthumously, or commercially without their approval.

The initiative mirrors similar conversations in Hollywood, where recent WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes demanded protections against AI use in writing, acting, and editing. “We’re at the same crossroads here in India. If we don’t set boundaries now, filmmakers may lose authority over their own stories,” Rai warned.

Will AI help or hurt Indian cinema?

Eros maintains that the original Raanjhanaa remains untouched and accessible to viewers, while the new Tamil version is simply a parallel “narrative experiment.” But for Rai, it’s not a question of access, but one of agency.

His fear is that AI, left unchecked, could replace artistic complexity with algorithmic storytelling designed for broader, safer appeal. “Art isn’t about pleasing everyone. It’s about saying something specific, something risky,” Rai says. “AI doesn’t take risks. It calculates.”

Still, he remains cautiously optimistic. “If used ethically and collaboratively, AI can elevate cinema. But without safeguards, it could flatten it.”

What’s next?

As Ambikapathy heads toward release, Rai’s call for artistic consent is gaining traction in industry circles. Filmmakers, screenwriters, and even some studio executives are reportedly discussing guidelines for AI use in creative workflows.

Rai’s next move will likely involve lobbying film guilds and copyright authorities to formally recognise AI-altered works as distinct creative entities, ones that must credit, consult, or exclude original creators based on their will. In the meantime, his own AI experiments will continue, under the same principle that guides his films: emotion over efficiency.