By Dr Roshan Doug

I have been a history enthusiast since my primary school days. In the 1960s I was part of the second generation of immigrants acquiring and adapting features of a foreign culture and its language. Integration was everything.

Although as pupils from the New Commonwealth we didn’t have role models or anyone who drew upon our own backgrounds and histories, I would get excited at the thought of school trips to places of British historical interest such as castles and cathedrals. I loved walking among their ancient walls, touching relics and artefacts that belonged to a distant time, a distant age. My imagination would be fired up. On my return, I’d expand on details by visiting my local library, reading history textbooks or select chapters and drawing/tracing pictures of people and monuments.

Today, however, it seems that despite the renewed interest in archaeology and genealogy, despite the numerous celebrity historians on TV, the subject doesn’t appeal to our younger generation. It doesn’t interest them the way it has interested me.

I thought of this in regard to the Black Lives Matter protests that have reignited the debate to "decolonise" the history curriculum. Do we need to review the contents and perspectives about Britain and her involvement in other countries? Of course, this debate concerns the legacy of more than 400 years of African slave trade, but it is equally relevant to our Asian communities who themselves are the products of British colonial rule.

Should we should mark historical figures like Edward Colston, Robert Clive, Cecil Rhodes, Thomas Macaulay and Robert Milligan - people who profited from colonialism? What is the role of history in schools – and is it even relevant anymore?

According to the Report on Race, Ethnicity and Equality in UK History (by the Royal Historical Society in 2018), BAME students are less likely than their white peers to choose history in examination or university applications. The report indicated that of the students entered for history at A-Level only approximately four per cent of students (in Year 13) were black and six per cent Asian.

Today it is difficult for BAME pupils to connect with the existing history curriculum because it denies them a claim in the dominant narrative. It doesn’t reflect their concerns or their cultural identity.

As a child I had no idea of the politics of education and, more specifically, the nature of history teaching. My parents used to recount stories of 'lived' experience, but somehow, I didn’t take them seriously. To me, the oral tradition wasn’t real; it wasn’t ‘proper’ history – the stuff from the O-Level syllabus. Neither did the school feel the need to fill me in with an Indian perspective or tell me about the advanced knowledge that existed in the Indus valley; the genocide of the Hindus by the Arabs and their programme of forced conversion; the jizyah that was forced upon the Indians; the desecration of temples and relics by Muslim rulers; the resistance of the Mughals by the Hindus such the Marathas; the achievements of Maharajah Ranjeet Singh, one of the most successful rulers in the world; the Sikh wars of the 19th century; the background to the Indian mutiny of 1857 and its British reprisal; the Amritsar massacre of 1919; the Indian freedom fighters like Udham Singh; the Bengal famine of 1943; the inhumanity of the British occupation that lasted more than 200 years and consisted of the humiliating ‘crawling orders’ for Indians and the gruesome capital punishments like blasting insurgents from the mouths of cannons, or the horrific stories of over 14 million Punjabis (among them my grandparents) about their experience of the Partition – the largest exodus of people in history.

There’s no doubt that during my formative years, I lacked confidence and felt embarrassed at my difference. There was no way I could have challenged the teachers let alone the curriculum.

In contrast, today’s Asian youngsters are very proud. They are savvy, a lot more forthright than my generation ever was and, what’s more, they seem to know so much. Social media and the democratisation of information have made political issues urgent – matters of life and death. You only have to look at the support climate change, environmental and ecological concerns or campaigns for social justice receive from young people. They clearly feel the urgency to connect, challenge and readjust the imbalances in our world.

So, why do they have a stark indifference to history?

I think it’s because the current teaching of history is monocultural, Euro-centric and politically skewered. Despite the changing world, the contents of today’s history syllabuses are still primarily conservative and sanitised with topics like the Tudors and Stuarts, the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the industrial revolution. History at school has a certain ideological slant that says something about nation building and national identity.

To correct that, our policy makers have to address Britain’s colonial role in perpetuating injustice and inequality such as its: exploitation of raw materials and human resources; mass inculturation; appropriation of cultural and intellectual assets; denigration of Indians and Hinduism as a ‘barbaric’ or ‘primitive’; enforcement of the ‘divide and rule’ policy; conversion of disaffected Indians into Christianity by stealth.

We cannot sanitise the part by simply ignoring it.

Is it any wonder that there’s a decline in the number of students taking history and particularly those from BAME communities?

To rejuvenate an interest in history, we need teachers from other cultural and racial background to give the subject relevance. Policy makers and education management should introduce ‘golden hello’ scheme to recruit more Asian graduates to teach history in the same way that our government lured maths and science graduates into the profession. We also need more Asian role models in the media and not just celebrity ‘historians’, but critics such as Pankaj Mishra, Shashi Tharoor and Rajiv Malhotra. These are revisionists challenging the canonical, entrenched and slightly falsified version of British history.

The subject needs to incorporate other dimensions, perspectives and interpretations. We need to devise new modules that are related to the legacy of the empire including immigration from the New Commonwealth, the challenges to race relations in Britain, multiculturalism, inner-city riots of the 1980s, and, religion and censorship.

Policy makers need to incorporate the compulsory teaching of other cultures and perspectives in history. We need to teach with the view that history contains a range of interpretations. Pupils need to consider, from whose point of view we are observing the past. What is our politics, our vested interest with history? How do we minimise bias or reflexivity when examining texts?

Finally, there needs to be an investment for schools in their development and adaptation of new resources and textbooks that provide a multicultural dimension to the subject. There is a need to establish an advisory board on resources from other cultural backgrounds that can supplement the existing history syllabi.

The 1970s integrationist approach to the teaching of history and subject contents certainly deprived me of my rich cultural heritage. To address that we seriously have to acknowledge the atrocities committed in the name of the empire. That would be a good start.

Dr Roshan Doug, MA, D.Ed, FRSA

Education consultant

Nigel Farage

Nigel Farage Rupert LoweGetty Images

Rupert LoweGetty Images

Rajan offers the pind daan in honour of his father and ancestors

Rajan offers the pind daan in honour of his father and ancestors

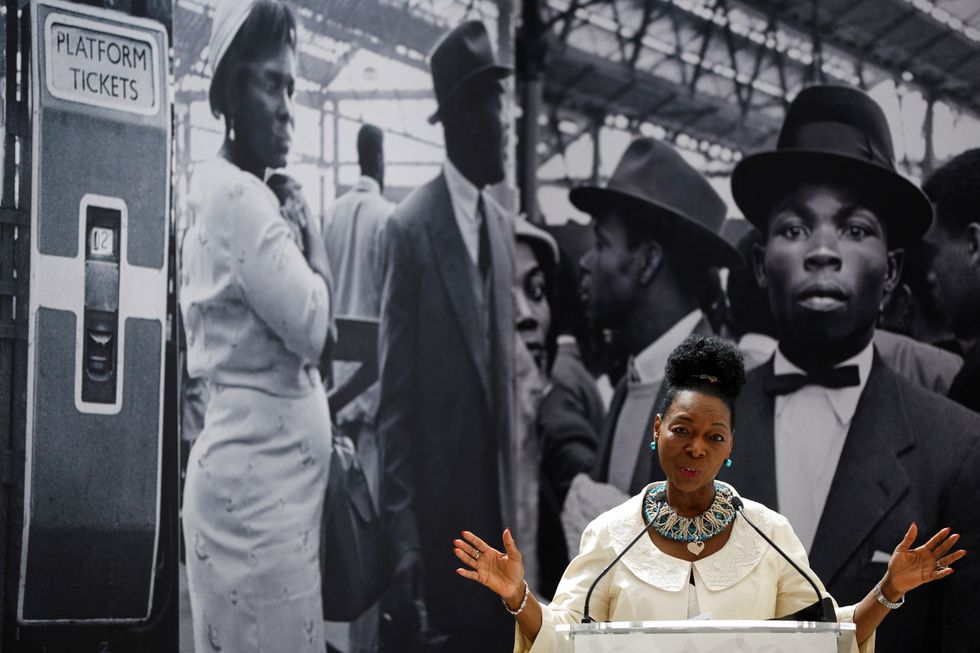

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’

Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’ Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’

Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’ Mahira Khan

Mahira Khan ‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience

‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’

Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’  John Abraham

John Abraham Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal

Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal  Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut

Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut Sana Yousuf

Sana Yousuf