THE son of a South Asian veteran of the Second World War has said stories like his father’s serve as a “powerful reminder” to Britain and the wider world of the sacrifices made by Asians during the war and in the years that followed.

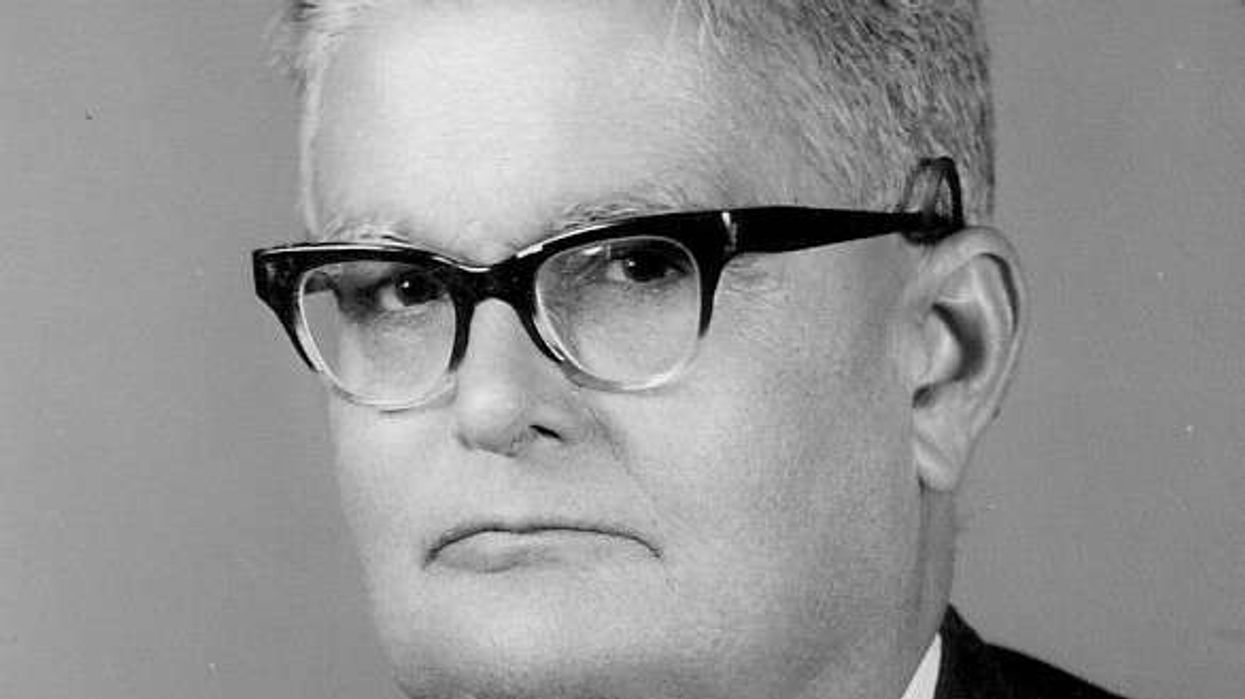

Mayurkant Baxi, 78, told Eastern Eye how his father, Shantilal Chunilal Baxi, endured hardship and discrimination in Uganda, yet continued to serve with courage, resilience and dignity – often without recognition for his efforts.

“My father was part of the reserve army in Jinja, Uganda,” Mayurkant, a retired aircraft engineer living in the UK, said.

“But he wasn’t on the frontline. Instead, he and other Indian soldiers were given tasks no one else wanted — cleaning human waste from buckets during nightly curfews, carrying it to collection points under the watch of British officers. It was hard, low-skilled, and humiliating work, but he never complained publicly.”

Shantilal was born in Jamnagar, Gujarat, on February 22 ,1909. After earning his BA and LLB, he moved to Uganda in 1934 to join his father, who previously had emigrated there.

Initially, Shantilal could not practise law, because Indian qualifications were not recognised under British law. He worked as a clerk in a janitor’s office, while preparing for the necessary exams, finally opening his legal practice in 1941.

Mayurkant said, “The law in Uganda was different from India, and my father had to prove himself all over again. But even while working on his career, he was deeply involved in social work. He looked after the Hindu cemetery, the local library, schools and the Asian community. He was the honorary secretary of the Jinja Chamber of Commerce for 20 years, all unpaid.”

During the war, Shantilal’s work in the reserve army placed him – in his thirties – at the time of these nightly, humiliating duties. “Black people were not allowed out after dusk. The Indians were the ones clearing the toilets,” Mayurkant explained.

“The British delegated the dirtiest work to us. And yet, my father continued to serve everyone – Africans, Muslims and Hindus alike. For him, everyone mattered.”

Shantilal was known for being a strict disciplinarian at home – “Even grown men would avoid him out of respect and fear” – but his influence extended through the town.

Children were disciplined with his name, “Maxi Kaka is coming,” and a road in Jinja, Baxi Road, still bears his family’s name.

After Uganda’s independence in 1962, Shantilal was awarded a British Government medal, around 1965, for his services to both the community and Her Majesty’s Government. Yet, as he held a British passport, he was unable to continue practising law under the new Ugandan regulations.

From 1964 to 1971, he worked for a company managing sugar and other factories, arranging work permits and business permissions for residents.

“The medal was just a small pin, but it meant so much,” said Mayurkant. “It was recognition for an Indian man in East Africa – something most other lawyers never received. He never sought wealth or fame; he just stood for what was right.”

When Ugandan dictator Idi Amin came to power in 1971 and expelled thousands of Asians, the Baxi family had already left. Shantilal moved back to India, settling in Khar West, near Mumbai.

His children also moved to India. “I went to India in 1960, because of education problems in Uganda,” said Mayurkant. “We bought a flat in Bandra, and I studied in Pune and Kerala. I later became a qualified aircraft engineer.”

Shantilal remained an avid traveller, visiting children and relatives in Kenya, the UK, the US, and Malaysia.

He passed away in 1985, aged 76, leaving behind a legacy of integrity and service.

Mayurkant’s own life mirrored some of the obstacles his father faced. Though educated in India, he was refused jobs at Air India and Indian Airlines, because he was considered a foreigner. He eventually moved back to Uganda, then secured a visa to the UK, where he qualified and worked as an aircraft engineer.

“I didn’t even know what the ‘colour bar’ was until I came to this country,” said Mayurkant, referring to how black and Asian people in the UK were treated differently in public places, especially in pubs.

People of colour were often forced to drink in separate rooms or were not served at all. Landlords could divide pubs into areas for white customers and separate “coloured” rooms.

Racial discrimination became illegal through the Race Relations Act of 1965, which made it unlawful to treat people unfairly in public places because of their race, colour, or country of birth. The law was strengthened in 1968 to outlaw discrimination in work and housing as well. Reflecting on both his and his father’s experiences, Mayurkant said the contribution of south Asians during the world wars are often ignored.

“People know there was poverty in India and many were desperate for work. Thousands of Indians came to east Africa or the UK, hoping for better lives, only to face discrimination,” he said.

Mayurkant said the lesson of his father’s life is simple, yet profound. “He taught us that all humans are equal. My blood is red, your blood is red. A black man’s blood is red. A white man’s blood is red. If a life can be saved, whose blood it is, shouldn’t matter. That’s how my father lived. That’s how I was brought up.”

With Remebrance Day round the corner, Mayurkant said he hoped stories of his father and other Asians will inspire recognition of the overlooked contributions of soldiers and civilians from the subcontinent.

“It’s not just about medals or pins,” he said. “It’s about honouring the courage and commitment of people who were made to do the hardest work, yet did it with pride and dignity.”

South Asian families in the UK are invited to share stories and photographs of relatives who served at https://www.myfamilylegacy.org.uk/