AN inquest has begun into the death of Harshita Brella, a 24-year-old woman from Corby, whose body was found in the boot of a car in east London. Police suspect her husband, 23-year-old Pankaj Lamba, is responsible for her murder.

At the hearing in Northampton, senior coroner Anne Pember said the provisional cause of death was "manual strangulation," with further toxicology and histology results pending. The inquest has been adjourned until 21 May 2025, and Brella’s body has not yet been released.

Meanwhile, detectives have renewed their plea for information as they work to uncover the events that led to her murder.

They have reviewed extensive CCTV footage from Corby and Ilford as part of their efforts to trace the suspect's movements. New images have been released to encourage anyone who may have encountered Lamba between the morning of 10 November, and the evening of 11 November, to come forward and assist the investigation.

Authorities believe he transported her body from Corby to Ilford, where he abandoned the car on Brisbane Road before fleeing the country. His whereabouts remain unknown.

Northamptonshire Police have also released a CCTV image showing him in east London after leaving the vehicle.

Police believe Pankaj Lamba murdered 24-year-old Harshita Brella in Northamptonshire earlier this month. (Photo: Northamptonshire Police)According to reports, Brella's death has raised concerns about domestic violence protections. She had been issued a domestic violence protection order in early September, but it lasted only 28 days.

Speaking in the House of Commons, Corby MP Lee Barron called the case "tragic" and questioned whether the government would extend the duration of such orders to better safeguard vulnerable individuals.

Deputy prime minister Angela Rayner responded, acknowledging that Brella "should have been protected" and reaffirming the government’s commitment to reducing violence against women by half.

Harshita was reported missing on 13 November after officers visited her home in Skegness Walk, Corby, following concerns for her welfare. Her body was found in the boot of a car in Brisbane Road, Ilford, east London, on 14 November. Police believe she was killed in Corby days earlier before being transported to London.

A post-mortem examination conducted at Leicester Royal Infirmary confirmed the preliminary cause of death as strangulation.

Detective chief inspector Johnny Campbell, leading the investigation, stressed the importance of maintaining the integrity of the case. “We are working tirelessly with our partners to secure justice for Harshita,” he said. “While we can’t comment on all aspects of the investigation, we are pursuing multiple leads.

"We know Lamba drove a silver Vauxhall Corsa from Corby to Ilford on the morning of Monday, 11th November. We believe Harshita’s body was placed in the boot before he set off. He abandoned the car in Brisbane Road and fled the scene.”

DCI Campbell urged the public to come forward with any information, no matter how small. “If you saw anything unusual or have any knowledge of Lamba’s movements, whether in Corby, Ilford, or elsewhere, please contact the police. Your information could help bring closure to Harshita’s grieving family," he said.

Pedro Pascal addresses fan backlash over playing Reed Richards at 50Getty Images

Pedro Pascal addresses fan backlash over playing Reed Richards at 50Getty Images

Kangana Ranaut speaks on equality and her role as a ParliamentarianGetty Images

Kangana Ranaut speaks on equality and her role as a ParliamentarianGetty Images  Kangana Ranaut calls equality a flawed idea, claims it’s ruining work ethic in today’s youthGetty Images

Kangana Ranaut calls equality a flawed idea, claims it’s ruining work ethic in today’s youthGetty Images Kangana Ranaut says belief in equality has created a ‘generation of morons’ in viral Times Now interviewGetty Images

Kangana Ranaut says belief in equality has created a ‘generation of morons’ in viral Times Now interviewGetty Images Kangana Ranaut blames equality for entitlement culture, says no two people are equalGetty Images

Kangana Ranaut blames equality for entitlement culture, says no two people are equalGetty Images

Actress Bella Thorne and Charlie Puth attend the Y100's Jingle Ball 2016Getty Images

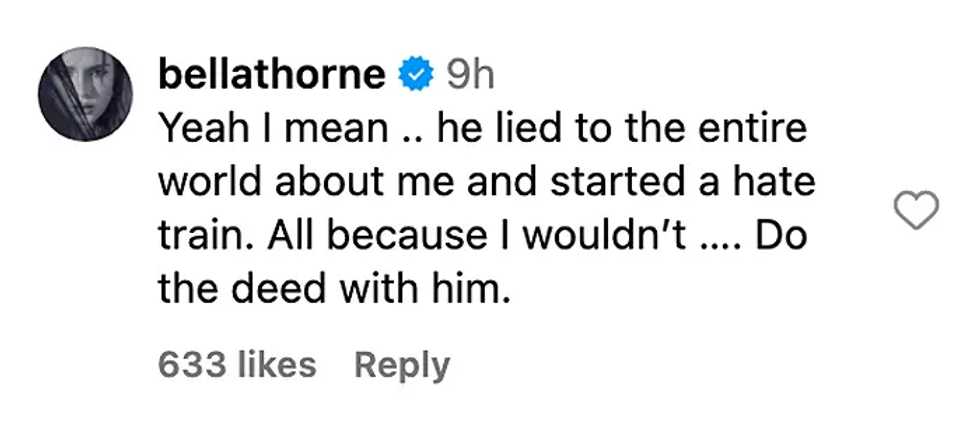

Actress Bella Thorne and Charlie Puth attend the Y100's Jingle Ball 2016Getty Images  Bella Thorne's commentInstagram Screengrab

Bella Thorne's commentInstagram Screengrab  Charlie Puth performs onstage at an interactive global eConcert liveGetty Images

Charlie Puth performs onstage at an interactive global eConcert liveGetty Images  Bella Thorne and Mark Emms attend a red carpet for the movie "Priscilla"Getty Images

Bella Thorne and Mark Emms attend a red carpet for the movie "Priscilla"Getty Images Charlie Puth and Brooke Sansone attend the 10th Breakthrough Prize CeremonyGetty Images

Charlie Puth and Brooke Sansone attend the 10th Breakthrough Prize CeremonyGetty Images