FOLLOWING the death of Pope Francis, the Vatican has entered a nine-day mourning period known as the Novendiale. The tradition, which dates back to ancient Rome, is observed before preparations begin for the election of the next pope.

Once the mourning period concludes, cardinals from around the world will gather in conclave to elect the next head of the Catholic Church.

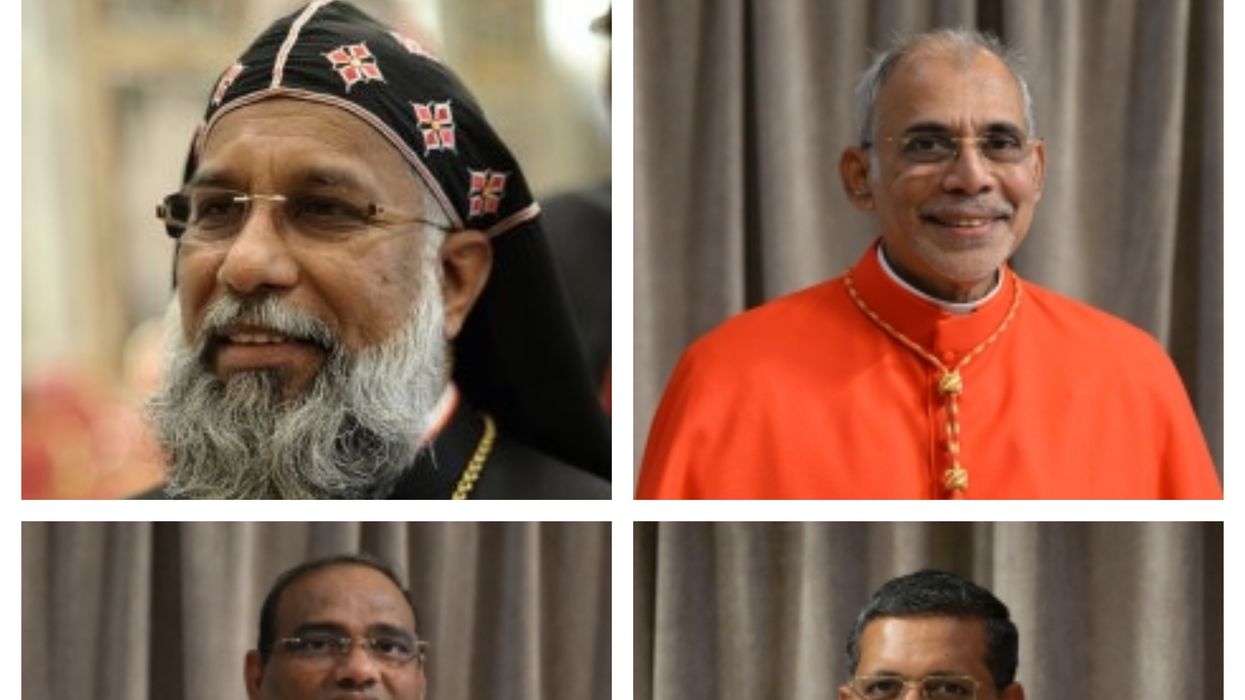

Among the 135 cardinals eligible to vote in the upcoming conclave, four are from India. They include Cardinal Filipe Neri Ferrao, Cardinal Baselios Cleemis, Cardinal Anthony Poola, and Cardinal George Jacob Koovakad.

Cardinal George Jacob Koovakad (51) is Cardinal-Deacon of S Antonio di Padova a Circonvallazione Appia and Prefect of the Dicastery for Interreligious Dialogue.

Cardinal Filipe Neri Antonio Sebastiao do Rosario Ferrao (72) is the Metropolitan Archbishop of Goa and Daman, President of the Conference of Catholic Bishops of India, and President of the Federation of Asian Bishops' Conferences.

ALSO READ: Who could be the next pope? A look at 15 likely successors

Cardinal Anthony Poola (63) is the Metropolitan Archbishop of Hyderabad.

Cardinal Baselios Cleemis Thottunkal is the Major Archbishop of Trivandrum of the Syro-Malankara Church and president of the Synod of the Syro-Malankara Church.

As of 19 April, there are 252 cardinals worldwide, of whom 135 are eligible to vote in the conclave.

The conclave traditionally uses smoke signals to communicate progress: black smoke indicates no decision, while white smoke signals the election of a new Pope.

Pope Francis died on Easter Monday, 21 April 2025, at the age of 88 at his residence in the Vatican’s Casa Santa Marta, according to a Vatican statement.

Born Jorge Mario Bergoglio in Buenos Aires, Argentina, he was ordained a Catholic priest in 1969. He was elected Pope on 13 March 2013, following the resignation of Pope Benedict XVI, and chose the name Francis in honour of Saint Francis of Assisi.

Prime minister Narendra Modi said he was “deeply pained” by the Pope’s death and called him “a beacon of compassion, humility and spiritual courage.” He added, “I fondly recall my meetings with him and was greatly inspired by his commitment to inclusive and all-round development.”

Pope Francis’s relationship with India included both hopes and challenges. His wish to visit the country remained unfulfilled, but he had recently elevated an Indian priest and Vatican official to the rank of Cardinal.

(With inputs from agencies)