by SAIMA RAZA

Manager at Croydon Community Against Trafficking

MODERN slavery is visibly invisible. It is prevalent on our high streets and it is thriving. It is only invisible insofar as we are unaware of its presence.

The main forms of slavery in the UK are sexual, labour and domestic. Historically, sexual exploitation was the primary form of slavery, but in recent years, we’ve seen labour slavery overtake other forms. It can now be found in industries ranging from fruit picking and fisheries, to local building sites and car washes. There are also incidents reported in local take-away shops, the hospitality industry, nail bars, hair salons and the kitchens of restaurants, as well as enforced begging (the recruitment of children and adults for purposes of begging) on our streets.

Slavery also extends to offences such as false imprisonment, rape, benefit fraud and sham marriages. Sexual slavery is a little more inconspicuous, but it can be present in small and large hotels, private homes, and flats above high street shops.

Domestic slavery may be virtually unnoticeable, whereby predominantly children (although adults, too) can be coerced and are bought to the UK for the purposes of domestic servitude. They may be required to cook, clean and babysit without pay, access to medical or educational help.

There have also been cases of organ trafficking, where people are smuggled into the country solely for the purposes of having their organs removed and sold on the black market.

These examples seek to illustrate that slavery is a burgeoning industry in seemingly normal places we frequent, where we socialise, shop and work. Essentially, anywhere there is a cash economy, the potential for exploitation is not far behind.

In 2015, the UK unveiled the seminal Modern Slavery Act, one of the few pieces of legislation of this kind in the world. It is a compendium of offences, civil orders and sentences, and seeks to consolidate offences that fell under the ambit of slavery and trafficking as well as impose a life sentence for traffickers. The Act focuses heavily on prosecution to deter traffickers and slavers.

It also created the Anti-Slavery Commissioners Office, a government body overseeing the UK’s response to this crime. It makes it incumbent upon businesses and commercial organisations with a worldwide revenue of over £36 million to publish a “modern slavery statement”, outlining steps they have taken to ensure their supply chains are free of modern slavery.

To date the conviction and prosecutions rate under the Act has been woeful; however, many argue it has only been in force for two years and needs time to gain momentum despite cases being bought forward to police forces across the UK.

Currently support for victims and survivors is regulated by the (European) Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings. This guarantees them rights to counselling, legal advice, education (limited to ESOL, English as a Second Language), maternal and sexual health services and housing. But with Brexit, it is unclear how or if the convention and its wide-ranging support provisions will be incorporated into UK domestic legislation.

One potential route may could be Lord McColl’s modern slavery victim support bill. The bill is more victim-centred and guarantees support to survivors. Currently, the support in the convention is limited to the time in which the Home Office makes a final decision on a person’s case – statutorily, it has allocated 45 days to make this decision. The bill seeks to extend support to those identified as victims for a further 12 months with a support worker.

It is a step in the right direction in terms of providing more comprehensive package of support, but the government is yet to support the bill.

Legislation is undoubtedly a powerful tool – to be able to say slavery is “illegal,” that it is a crime, is quite impactful. It does not leave room for doubt, to question its objectivity.

While the UK hosts some of the most compelling laws against slavery, there is still some way to go. One of the key challenges I came up against in my role as a front-line caseworker working directly with victims of slavery was that while we were able to offer them support, the percentage of victims who received positive trafficking decisions – the UK government accepted they were trafficked and granted stay as a result – is feeble.

A negative decision means they remain an irregular migrant. This insecure immigration status leaves them vulnerable to re-exploitation in the UK and they are in danger in their source country if asked to return. Additionally, children of victims are not offered any specialist care and often fail to meet the criteria for support from local social services.

As a caseworker, one of the more frustrating aspects was that clients could not access any support, including legal aid, if they did not consent to entering the National Referral Mechanism and essentially engage with the immigration process. In the event they are granted stay in the UK, some are not given the right to work, preventing them from becoming economically independent and keeping them reliant on donations, food banks and local charity projects for their daily needs. These can act as powerful deterrent for victims to come forward.

Domestic workers are another vulnerable group who may be in positions of slavery, but are unable to access the same protections as victims, especially those linked to their employers.

Slavery is a behemoth, it is a colossal challenge and one that cannot be overcome if we do not employ a multi-faceted, multi-layered approach with action ranging from government to our neighbours. The message ought to be, it is most likely happening in an area you know.

The UK boasts a number of excellent and inspiring charity projects that provide support to victims and survivors. They fill a void that the statutory sector does not have the resources to address. I have always advocated for a multi-agency response, one that is coordinated, intelligent and compassionate.

At Croydon Community Against Trafficking, we tell people modern slavery is pervasive in our towns and cities. We continue to reach more people than ever but the message about trafficking and slavery needs to be louder and more persuasive. The charity I work with seeks to undertake preventative work, but much of the sector is reactive, they wait for help when victims are identified. We gather intelligence to disrupt the activities of traffickers, and submit this information to the council and police.

Our community engagement programme trains people across Croydon and London on the issue of modern slavery, signs to look out for and whom to report to. Our work in schools concentrates on helping young people understand their vulnerabilities and how to mitigate them. We also undertake campaigning work along with liaising with local movements, MPs and councillors to ensure that we respond to modern slavery and prevent vulnerable people from becoming victims in the first place

Modern slavery is hidden in plain sight – this mass commodification of people numbers in the millions across the globe. We have to do better at ‘seeing’ them.

Nigel Farage

Nigel Farage Rupert LoweGetty Images

Rupert LoweGetty Images

Rajan offers the pind daan in honour of his father and ancestors

Rajan offers the pind daan in honour of his father and ancestors

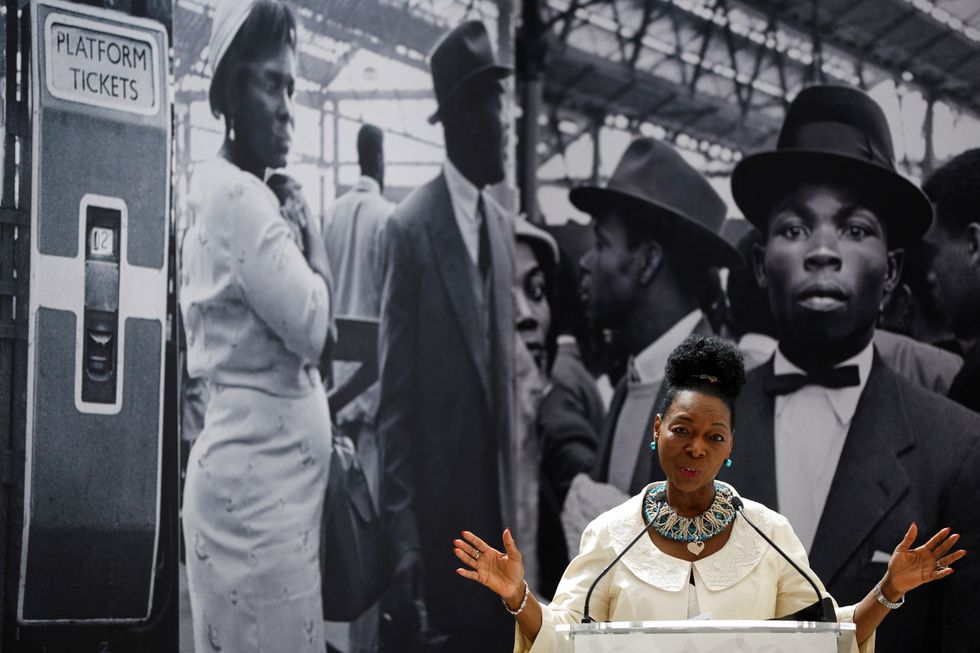

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’

Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’ Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’

Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’ Mahira Khan

Mahira Khan ‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience

‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’

Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’  John Abraham

John Abraham Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal

Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal  Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut

Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut Sana Yousuf

Sana Yousuf