By Amit Roy

SHAKESPEARE plays you did at school tend to stay with you.

In my case, it was Julius Caesar in India – you got a cuff round the ear if you got a word wrong in reciting passages that we had to learn by heart – and Twelfth Night in England.

But I never thought Shakespeare was racist – and still don’t. However, in the campaign to “decolonise” western culture in the aftermath of Black Lives Matter, even the Bard’s plays are not escaping scrutiny.

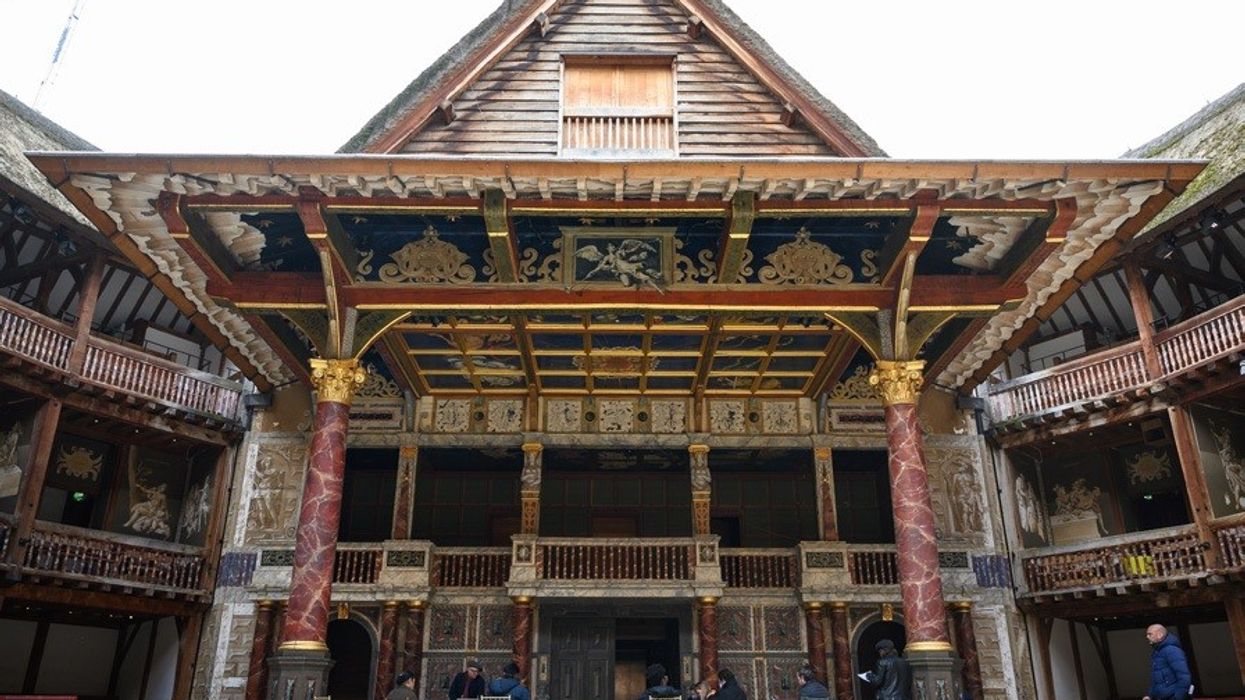

“Anti-racist Shakespeare seminars” have been held at the Globe Theatre, which was built on the South Bank in London to resemble the Elizabethan venue for which he wrote his plays more than 400 years ago.

Academics and theatre practitioners have been examining how Shakespeare cast “dark” as negative, but “fair” as positive.

The project seems relevant for a country like India, because there is a premium on “fair-complexioned brides” in Indian society and a market for skin-lightening creams such as Fair & Lovely .

A Midsummer Night’s Dream endorses the view that “white is beautiful, that fair is beautiful, that dark is unattractive”, said actor and seminar speaker Aldo Billingslea, making the play problematic from the first line, “Now, fair Hippolyta.”

The preference for white over black is evident in the lover Lysander’s statement “who would not trade a raven for a dove?”, Billingslea said, because it is a line “attributing value to these (birds) because of their colour”.

Shakespearean scholar Sir Stanley Wells has argued there is no need to decolonise the Bard. “I think the terms fair and dark are very multivalent words. Fair can mean fair of skin, or in the aesthetic sense of beautiful, or in the behavioural sense. The contrast of light and dark is also, I would say, a human universal.

“I think Shakespeare plays with these different meanings, and these different shades of meaning. I would not represent Shakespeare as a racist, I think he is far more subtle in his portrayal of characters than that.”

Over the years I have wondered more about The Merchant of Venice, where Shylock, the Jewish moneylender, is finally forced to convert to Christianity by way of punishment. Make the moneylender Muslim – and you have a play for today.