AHEAD of Lisa Nandy’s forthcoming visit to India, her first overseas trip as secretary of state for culture, media and sport, the British Council has told Eastern Eye this government organisation is intent on projecting a positive and progressive image of Britain in its dealings with Indian partners.

“We need to shine a light on how multicultural Britain has become,” Dr Debanjan Chakrabarti, British Council director for east and northeast India, told Eastern Eye at his office in Kolkata.

He added the British Council has brought “thought leaders and engineers and the best writers from all communities” to send a clear message that Britain is “no longer monocultural or monolithic”.

Chakrabarti explained why the culture secretary’s trip to India is important: “We are an arms-length body, but work very closely with His Majesty’s government.

“Here in India, we have three major sectors of work – education, culture and the creative economy. In arts and culture, we have a focus on festivals, working in partnership with the British and Indian festival sectors.”

At a time when some institutions in Britain are following US president Donald Trump’s example and scrapping their diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) targets, the British Council is standing firm.

It is sticking to its mission statement: “We connect. We inspire. We support peace and prosperity by building connections, understanding and trust between people in the UK and countries worldwide. For 90 years, we have shaped brighter futures through education, arts, culture, language, and creativity.”

The UK and India are strengthening their relationship not only through business – both sides are trying to finalise a far-reaching Free Trade Agreement (FTA) – but also through culture and especially promoting the English language.

Nandy is the only person of Indian origin in Sir Keir Starmer’s cabinet. Her father, Dipak K Nandy, who was born in Kolkata in 1936 and emigrated to Britain in 1956, turns 89 on May 21. He was an academic who was active in race relations and was the first director of the Runnymede Trust.

Chakrabarti said Nandy is “coming on an invite from India’s minister of information and broadcasting, Ashwini Vaishnaw, sent on behalf of prime minister Narendra Modi.

“She is one of the keynote speakers at the World Audio Visual Entertainment (WAVE) summit, which is in Mumbai from May 1-4. This is one of those huge business to business conferences that moves around the world. This year it is happening in Mumbai, and this a huge achievement for India to be able to host the summit. It’s a very prestigious event.

“She has a number of other meetings that we are lining up in the culture and creative industries, in sports and tourism. After Mumbai she will be in Delhi where I expect to meet her.”

Chakrabarti said colleagues who have dealt with Nandy found “she is proud of her Kolkata Bengali heritage”.

Nearly 78 years after Indian independence, it will be part of Nandy’s mission to reinforce the message that the days of the Raj have long since gone and that she represents a very different Britain. That shouldn’t be a too difficult, as she comes from a country that has had Rishi Sunak as prime minister.

Language is the carrier of culture, but the British Council is careful about the way it promotes English in India. In a country with over 120 languages and 270 mother tongues, English remains the link language. It has, in effect, become another Indian language. Aspirational parents insist on sending their children to English medium schools.

The British Council’s approach aligns with India’s education policy, which requires children to be taught in their mother tongue first, with English introduced at about age nine or 10, although private schools start English right from the beginning.

Chakrabarti, whose own PhD in media and culture studies is from Reading University, said: “I’m not only the area director, but I’m also one of the south Asia research champions for the British Council. I help in the advocacy of the research that we commission, and my own background in policy research helps in this.

“We have put together enormous international data that suggests that multilingual children have better cognitive skills. We also found out that south Asia, particularly India, has relatively fewer incidents of age-related ailments such as dementia and Alzheimer’s compared to monolingual nations.

“There are clinical advantages. The brain is ticking when you switch languages. ‘Translanguaging’ makes a difference. If someone can write across different script systems, if they can read the Roman script, but also Bengali or Hindi, the brain is clinically better.”

Chakrabarti pointed out: “One of the really interesting recommendations from that research in India has application for inner city schools in Britain, as the country becomes more multilingual.

“Many British primary schools will have children coming from households which may not have English within their communities. India’s cities have large migrant populations from all over India.”

In the area of English language teaching, the collaboration is with the universities of Cambridge and Reading. A leading role is being played by professor Ianthi Maria Tsimpli, chair of English and applied linguistics at Cambridge University.

Although Cambridge has so far not been willing to open a campus in India (despite the efforts of Cipla chairman Dr Yusuf Hamied, an honorary fellow at his old college, Christ’s), Britain’s top university “has a very large number of research collaborations in India”, Chakrabarti said.

Eastern Eye noticed the British Council offices in Kolkata were being used mostly by young women working on their laptops.

“We have three libraries in India – in Delhi, in Kolkata and in Chennai,” said Chakrabarti. “We run English language teaching centres as part of our English in schools education portfolio.”

The engagement between the UK and India appears to be a close one.

Chakrabarti added: “We have fantastic research partnerships between British and Indian universities. Kolkata was ranked India’s top city for science research by Nature journal in December 2024. We are here to promote two-way traffic in education and cultural conversations. Currently, there’s a very big and impactful project running, which focuses on women in space.

“This is part of a wider programme that the UK had pioneered in promoting women in leadership roles. In science, there is a particular focus on STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics). In some areas, they are a priority for both countries, for example, in climate change and sustainable development.”

The British Council is also collaborating with partners in Dhaka after winning “one of the 17 bids worldwide for a project that will look at the confluence of culture and climate change in Sundarbans (the mangrove forests that are shared by West Bengal and Bangladesh and where human beings and tigers have come into conflict). We are supporting the research side of this project. We are trying to look at how climate change is impacting the composite and syncretic culture of the Sundarbans.”

The British Council has facilitated many cultural exchanges.

Chakrabarti said: “The Kolkata-based Pickle Factory dance foundation is run by Vikram Iyengar, who went to Aberystwyth in Wales for his creative education and has had some fantastic collaborations with cutting-edge theatre companies in the UK.

“The focus for us is (bringing) new talent (to India). In 2024, the UK was the theme country for the Kolkata International Book Fair.

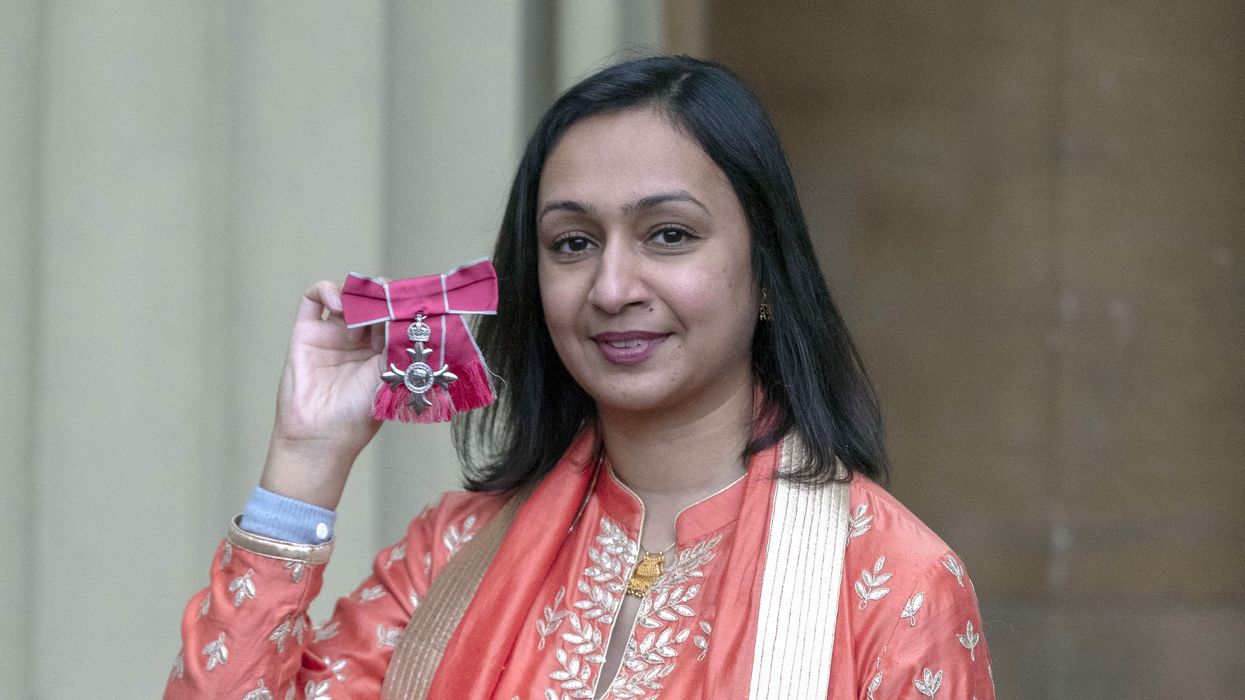

“We had 30 authors and thought leaders who came and talked about their work. They included the very exciting engineering talent, Roma Agrawal, part of the design team at the Shard in London.”

The NewScientist did a piece on her headlined: Roma Agrawal: The amazing engineer who designed the Shard’s spire. Structural engineer Roma Agrawal was part of the team that designed the spire topping London’s tallest building.”

Chakrabarti continued: “We also had Daniel Hahn, one of the most noted translators from the UK.”