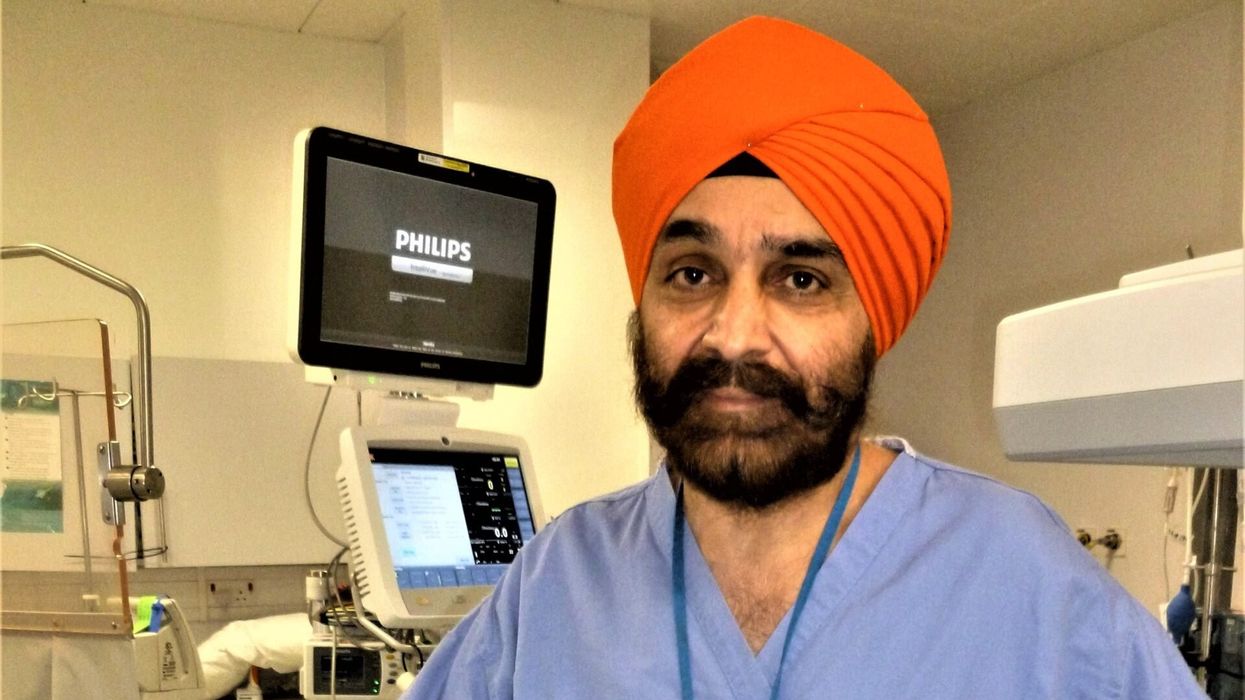

PROFESSOR Jaspal Kooner, one of Britain’s most eminent cardiologists, has been trying to find out why Asians are so prone to heart attacks, diabetes and kidney disease – and what he can do to help them. “Compared with the white population, Asians are at two-fold higher risk of cardiovascular disease, three-fold higher risk of diabetes and five-fold higher risk of kidney failure,” said Kooner, who is Professor of Clinical Cardiology at Imperial College London and consultant cardiologist at Hammersmith Hospital.

A Fellow of the Academy of Medical Sciences, he has done over 20,000 heart operations over the last 20 years and trained 200 cardiologists. He was born in Kenya, came to Britain aged 12 in 1968, went into medicine, and was named “Doctor of the Year” across the NHS in 2004. He has been able to pick up his fundamental research which was stalled by the pandemic. His idea is to select 75,00 healthy Asians in the UK, another 200,000 in the subcontinent, follow them over many years and then try and analyse why some develop disease while others manage to escape.

What’s their secret? He believes once he has been able to identify the genetic differences between the two groups, drugs could be developed to help those deemed vulnerable. At Hammersmith Hospital, Kooner can often be found in the operating theatre trying to save the lives of his patients, some in their 30s.

Speaking from outside the theatre, the professor told GG2 Power List: “On the one hand, you’re trying to understand the disease to stop this epidemic at the local, national or international level – this can potentially benefit mil lions of people. On the other hand, you have your patient in front of you and you’ve got to do the best for them. You have an immense responsibility for patients.” He explained the science behind his research, which is funded by the Wellcome Trust: “The idea behind collecting this data is to set up ‘biobanks’, a biological resource to be able to answer important questions about why south Asians have higher rates of heart disease and diabetes. Despite decades of research, the answers to these questions have not been forthcoming. And, realistically, the only way of answering the questions is to put together large datasets of participants from diverse back grounds – and to then follow up the health of these individuals.” Choosing the right people is an elaborate process. “When you assemble a cohort you in vitepeople to come and participate in research. They go through an assessment which includes consent for us to be able to follow their health.

They answer questions relating to lifestyle, past medical history, smoking, alcohol. Then they have a physical assessment which includes measurements of things like body mass index, body fat, ECG, retinal photography, diet, physical activity and blood sampling. The blood samples have to be processed and stored in – 80C fridges to be analysed over years to come.” In the UK, research centres have been established in five different parts of London, Birmingham, Manchester, Leicester, Leeds and High Wycombe. “Then we have centres across India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka.” There are important genetic differences across south Asia, said Kooner, the project’s director. He explained the Asian conundrum: “There’s no question that cholesterol, smoking, blood pressure, physical activity and diet contribute to risk in Asians in the same way they do in Europeans. But when you’ve taken all of that into account, you’re still left with this gap in knowledge of a two-fold excess risk of heart attacks in Asians, a three-fold excess risk of diabetes, and up to a five-fold excess risk of kidney disease.” Kooner said the mystery had not been resolved in the past 20 years.

“So the new way of addressing these issues is take what we now call in science an ‘agnostic’ approach. That is saying, I’m not approaching this whole issue with a hypothesis of one particular risk factor in mind. I’m now going to take an overview. And I’m going to look at this large dataset that we have and how at the beginning, they are all healthy. But 20 years down the line, let’s say for argument’s sake 10,000 people have had heart attacks and the other 90,000 have not. Then you look at differences in the patterns. How does the genome differ in one population compared to the others? How do proteins differ in one pool to the other? How do the metabolites differ in one to the other? Modern science allows us now not to look at just one gene but all the genes, not one metabolite but all the metabolites, not one protein but all the proteins.” Kooner went on: “Once you identify what the patterns are, then you can begin to develop what we call biological pathways. You can see which biological pathways are disturbed and cause disease and which don’t. That understanding has two outcomes. You can then look towards identifying drug targets, where the bio logical pathways are disturbed. And the second thing, of course, is that you can identify people who are at high risk compared to those who are at lesser risk. So you’re able to stratify your population and say, well out of 100,000 people, these are the 10,000 people who are on the wrong trajectory.

I’m going to pick these out first. And I’m going to address my efforts on prevention, investigation and treatment of these 10,000 because that’s where the big risk lies.” Kooner is optimistic that the large cohorts will provide answers that have hitherto eluded medical science. He said: “I’d like to think that within the next five to 10 years, we will have emerging answers. The first thing obviously is to create this resource because without the resource, you can’t do anything. Going back 100 years, this is one of the largest resources in the world. Having assembled the resources, our plan is to start the analysis. That takes time and requires partnerships with aca demic institutions, biotechnology companies, and with pharma.” Incidentally, Kooner has kept his trim figure. Though a Sikh, he steers clear of rich Punjabi dishes such as butter chicken. “I have no more than one chapati for dinner,” he revealed.