LORD MOUNTBATTEN ‘UNDERSTOOD THEIR VERY SPECIAL RELATIONSHIP’, SAYS AUTHOR

by AMIT ROY

A NEW book on the Mountbattens reveals that Lord Louis Mountbatten and his wife, Edwina, one of society’s most glamorous couples, had a remarkably open marriage.

And, far from being jealous, Lord (“Dickie”) Mountbatten was proud of Edwina’s close relationship with Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister.

Since Mountbatten was the last British viceroy sent out by the Labour prime minister Clement Attlee in 1947 to preside over the transfer of power and the creation of the new state of Pakistan following a bloody partition, The Mountbattens: Their Lives and Loves by Andrew Lownie (Blink; £20), will grip Indian and Pakistani readers.

Lownie poses the question about Edwina and Nehru that has never really been answered satisfactorily: “What was the nature of her relationship with Nehru?”

The author says: “Edwina’s authorised biographer, Janet Morgan, has claimed, having talked to ‘those who knew them well’, that it was purer than a physical relationship, that Nehru respected Dickie and would not have abused that trust.”

He adds that the Mountbattens’ younger daughter, Lady Pamela Hicks, “said it was platonic”.

Also “Mountbatten’s grandson, Ashley Hicks, claims Nehru’s sister (Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit who was once Indian high commissioner in London) revealed that he was impotent and therefore there could not have been a physical relationship with Edwina.”

Lownie himself inclines to the opposite view. “Richard Hough, the author of several books on the Mountbattens and who interviewed Edwina’s sister, later wrote, ‘Mountbatten himself knew they were lovers. He was proud of the fact, unlike Edwina’s sister who deplored the relationship.’ Marie Seton, a friend and biographer of Edwina agreed: ‘I really don’t know about the physical side of their affair – I’d think probably yes.’”

Nehru’s biographer, Stanley Wolpert, wrote that because of the relationship, “Nehru’s daughter Indira (Gandhi) hated her (Edwina)”, Lownie says.

But does any of this matter? The conventional theory is that because of the Mountbattens’ friendship with Nehru and their antipathy towards Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who had demanded a separate homeland for India’s Muslims, the latter was forced to accept “a mutilated, moth-eaten Pakistan”.

Jinnah died of cancer on September 11, 1948, barely a year after independence.

According to Lownie, “Mountbatten later reflected that if he had known the seriousness of his [Jinnah’s] illness, he might have delayed independence, and there might have been no partition.”

Lord Mountbatten and Edwina Ashley were married at St Margaret’s Church, Westminster Abbey, on July 18, 1922. The wedding was attended by King George V and Queen Mary, and with the then Prince of Wales acting as best man.

Lownie produces plenty of evidence to show Mountbatten was bisexual. It was certainly an unusual marriage – “one that was loving and mutually supportive, but also beset with infidelities. As Dickie would later claim, ‘Edwina and I spent all our married lives getting into other people’s beds.’”

No one questions the fact that Edwina and Nehru loved each other. In October 1948, when he came to London for discussions on the Commonwealth, which India had decided to join, “Dickie tactfully left the reunited lovers alone for a midnight rendezvous en route from the airport. ‘Too lovely,’ Edwina noted in her diary.”

Lownie goes on: “For the next week they were inseparable. They visited Jacob Epstein’s studio, Edwina joined Nehru on the platform at a meeting in Kingsway Hall, they saw Euripides’ Medea, jointly attended the Lord mayor’s banquet, a reception at the King’s Hall and a dinner for Dominion Premiers at Buckingham Palace, and were photographed at a Greek restaurant in Soho after the press were tipped off by Krishna Menon (then the Indian high commissioner in London).”

Nehru was soon “back with Edwina at Broadlands (the Mountbattens’ home in Hampshire). It was a relationship that suited them well. Politically, emotionally and intellectually compatible, they drew support from each other. He bought her small exotic gifts, welcome in Britain still in the grip of rationing, such as mangoes from India, cigarettes from Egypt, a Gruyère from Switzerland, but he brought much more. Where Dickie had been too gauche, busy or casually dismissive, here was a man with whom she felt comfortable and an equal, who respected her mind and knew how to appeal to her feelings.”

After the death of King George VI in February 1952, Edwina, hospitalised with a haemorrhage and worried she might also die, “passed Nehru’s letters to her husband for safekeeping”.

Her letter said: “You will realise that they are a mixture of typical Jawaharlal letters full of interest and facts and really historic documents. Some of them have no ‘personal’ remarks at all. Others are love letters in a sense, though you yourself realise the strange relationship – most of its spiritual – which exists between us. J had obviously meant a great deal in my life, in these last years, and I think I in his too. Our meetings have been rare and always fleeting, but I think I understand him, and perhaps he me, as well as any human beings can even understand each other… It is rather wonderful that my affection and respect and gratitude and love for you are really so great that I feel I would rather you had these letters than anyone else, and I feel you would understand and not in any way be hurt – rather the contrary. “

After asking his daughter Pamela to vet the letters first, Mountbatten took a year to reply: “I’m glad you realise I know and have always understood the very special relationship between Jawaharlal and you, made the easier by my fondness and admiration for him, and by the remarkably lucky fact that among my many defects God did not add jealousy in any shape or form. ..That is why I’ve always made your visits to each other easy...”

Edwina died suddenly, aged 59, on February 21, 1960, in British North Borneo (now Sabah), while on an inspection tour for the St John Ambulance Brigade. Her body was flown back to England. In accordance with her wishes, she was buried at sea off the coast of Portsmouth from HMS Wakeful on February 25, 1960.

Lownie writes: “Dickie, in full admiral’s uniform, tears streaming down his face, gently kissed his all-white wreath and tossed it into the sea. A cable away on the Indian frigate the Trishul, Krishna Menon, Indian defence minister, dropped a farewell garland of marigolds from Nehru.”

Incidentally, Edwina’s letters to Nehru are with Sonia Gandhi and her family in India and remain strictly and possibly forever under lock and key.

Lunchbox is a powerful one-woman show that tackles themes of identity, race, bullying and belongingInstagram/ lubnakerr

Lunchbox is a powerful one-woman show that tackles themes of identity, race, bullying and belongingInstagram/ lubnakerr She says, ''do not assume you know what is going on in people’s lives behind closed doors''Instagram/ lubnakerr

She says, ''do not assume you know what is going on in people’s lives behind closed doors''Instagram/ lubnakerr

He says "immigrants are the lifeblood of this country"Instagram/ itsmetawseef

He says "immigrants are the lifeblood of this country"Instagram/ itsmetawseef This book is, in a way, a love letter to how they raised meInstagram/ itsmetawseef

This book is, in a way, a love letter to how they raised meInstagram/ itsmetawseef

The crew of The Ministry of Lesbian Affairs

The crew of The Ministry of Lesbian Affairs

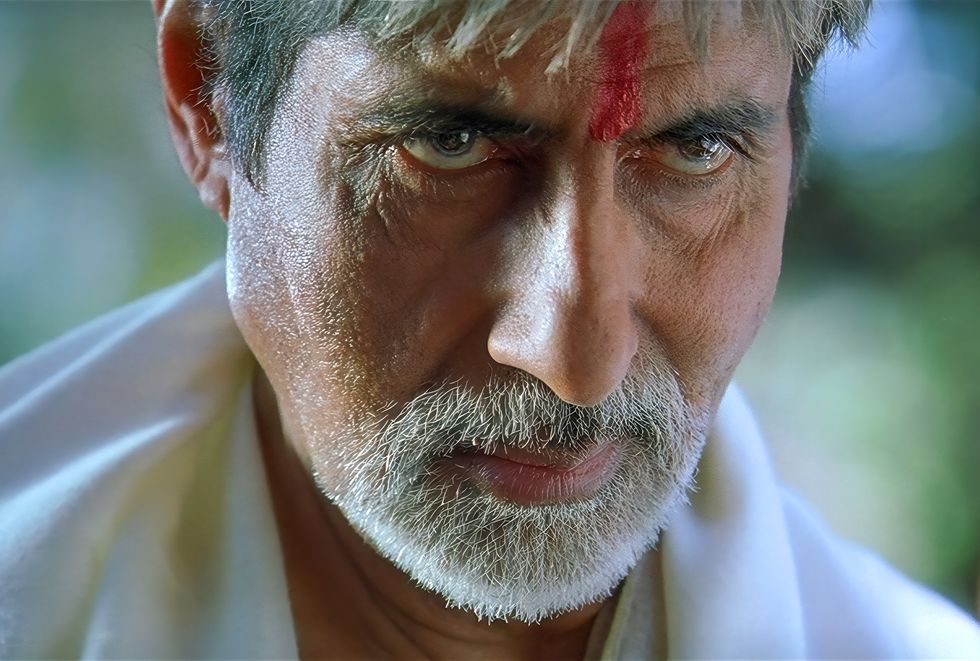

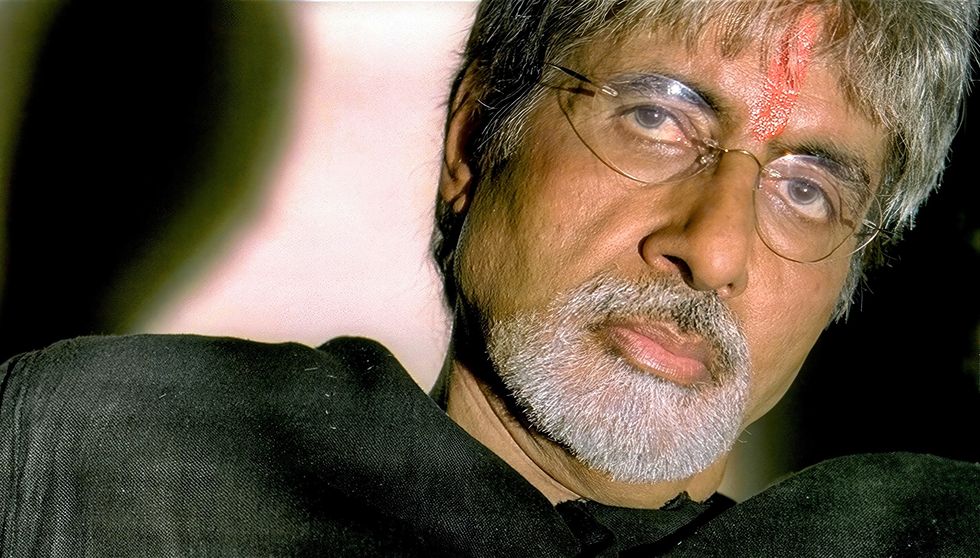

A still from Sarkar, inspired by 'The Godfather' and rooted in Indian politicsIndia Glitz

A still from Sarkar, inspired by 'The Godfather' and rooted in Indian politicsIndia Glitz Sarkar became a landmark gangster film in Indian cinemaIndia Glitz

Sarkar became a landmark gangster film in Indian cinemaIndia Glitz The film introduced a uniquely Indian take on the mafia genreRotten Tomatoes

The film introduced a uniquely Indian take on the mafia genreRotten Tomatoes Set in Mumbai, Sarkar portrayed the dark world of parallel justiceRotten Tomatoes

Set in Mumbai, Sarkar portrayed the dark world of parallel justiceRotten Tomatoes Ram Gopal Varma’s Sarkar marked 20 years of influence and acclaimIMDb

Ram Gopal Varma’s Sarkar marked 20 years of influence and acclaimIMDb

The statues were the product of a transatlantic effortGetty Iamges

The statues were the product of a transatlantic effortGetty Iamges