By Amit Roy

“INDIA’S finest actor” is a phrase that has been used loosely in recent years, but Soumitra Chatterjee, who died last Sunday (15) at the age of 85, has to be included in this group.

Soumitra, who succumbed to Covid-related complications more than a month after being admitted to a hospital in Kolkata, acted in many films, but his claim to fame rests on the 14 movies directed by Satyajit Ray. He made his debut as a 23-year-old in the final part of the Ray trilogy, Apur Sansar in 1959.

The three films –which I commend to Eastern Eye readers as the very best in world cinema – passed me by until a friend in Calcutta (before the city’s renaming in 2001) took me to see Pather Panchali, the first part of the trilogy.

When first released in 1955, it was hardly a hit in Calcutta. But Ray’s tragic yet lyrical depiction of the harshness of life in rural life in Bengal was named “best human document” at the Cannes Film Festival in 1956.

Little Apu loses his sister Durga in Pather Panchali. In Aparajito, the second film in the trilogy, he leaves his village to seek college education in Calcutta.

Apu is short for Apurba Krishna Roy, a young man in Apur Sansar. Also making her debut opposite Soumitra was a schoolgirl, Sharmila Tagore.

On Soumitra’s passing, Sharmila recalled: “I was 13 years old and he was 10 years elder to me when we started working in Apur Sansar. In the film, those beautiful dialogues that we spoke to each other also endeared us to each other. I really respected and admired him, and what he stood for. He was one of my oldest friends, after my husband Tiger (cricket legend Mansoor Ali Khan Pataudi) and actor Shashi Kapoor. He has been such a loyal and fun friend.”

Sharmila plays Aparna, whom Apu marries in unusual circumstances. A friend invites Apu to attend a family wedding in a village in Bengal. Just before the ceremony, the intended bridegroom turns out to be mentally unhinged. Apu is pressured by his friend to “stand in” for the discarded bridegroom and pretty much forced to marry Aparna before the auspicious time (lagna) decreed by priests comes to an end.

He brings her to Calcutta to share his impoverished lifestyle and we see tender love developing between the couple. But tragedy is around the corner. Apu bids farewell to a pregnant Aparna as she goes back to her paternal home for the birth of their child. Not long afterwards a relative brings news that Aparna has died in childbirth.

Apur Sansar, which remains one of my favourite films, ends on a positive note. Apu goes back to meet his little son, whom he has never seen, and returns with him to Calcutta to begin a new life together as father and son.

It was at university that I chanced one afternoon on Apur Sansar. I remember it was still light when I came out after the film had finished, but its impact on me was such that I was unable to speak for an hour or so. My mother had died a few months earlier at a relatively young age in London and seeing the film brought it all back.

It so happens I got to meet Soumitra on a fine spring day in London in April 2009. He had come for possible treatment after a cancer scare. He was staying with friends in north London and possibly because he was away from crowds of Kolkata, he opened up, probably like never before.

I remember there was a bunch of daffodils in a vase behind him as he played me a little piano. He told me his pick of western classical music would include Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons and Beethoven’s Choral Symphony. The films he would take to a mythical desert island would include Charlie Chaplin’s 1925 movie, The Gold Rush, as well as Pather Panchali and Charulata, which some regard as Ray’s best work.

Soumitra said he had seen Pather Panchali 30- 40 times. In common with another of his favourites, Vittorio De Sica’s The Bicycle Thief, made in 1948, “they are classics. They transcend time. People will see them as long as there is cinema.”

“As a student of cinema, Pather Panchali is the weakest of Satyajit Ray’s films,” he said. “It is the second, Aparajito, which is technically perfect. But Pather Panchali has such vitality and life force that I have not seen a human unaffected by it.”

He said that under doctor’s orders, his diet was a bit restricted. Speaking in a mixture of Bengali and English, Soumitra, probably an orthodox Hindu back home, made me laugh by saying he would “quite like to fit in a nice, juicy steak with some excellent red wine – prochur wine khabo, prochur (I shall drink lots of wine, lots)”.

Though he had intimations of mortality, he wasn’t afraid of “the end”.

“Time is very precious. It has become shorter now, I can almost see the end,” he observed. “The end is inevitable, you know. It is useless to be afraid of it. I am only afraid of physical pain and nothing else. I wonder if at the end I will be able to preserve my dignity. I don’t want to lose my dignity even when I am going away.”

He spoke of the resilience of the human spirit. “By and large, I am ok. No one wants to die. I don’t either, but I have learnt to accept that it will come. At some point, life transforms itself into death.”

In more than a month in London he had managed to fit in daily walks, some sightseeing (a trip to Yorkshire), catch up at home with movies (Il Postino, an Italian film; Behind the Sun, from Brazil; the Czech film Kolya; and The Lives of Others) and take in a play at the National Theatre, Death and the King’s Horsemen, by the Nigerian Wole Soyinka.

Unlike Sharmila, who developed a second career in Hindi cinema with films such Kashmir Ki Kali, Aradhana, Amar Prem, and Mausam, he explained his decision not to move to Bombay [now Mumbai] with the aim of making a fortune in Bollywood: “There are executives in Calcutta who earn more than me. But to go to Bombay would have meant reorienting my mind which was not possible for me.”

He estimated he had read 8,000 books over the years. His choice for a desert island would be the Mahabharat. He enjoyed contemporary Indian writers in English, and his favourite was Amitav Ghosh, especially the author’s The Glass Palace and The Hungry Tide. “It is written in very competent English, but I feel it is part of Bengali literature.”

Some years ago I used to co-present Footlights, a weekly arts programme on Avtar Lit’s Sunrise Radio. One bit of music – composed by Pandit Ravi Shankar and that I loved playing – comes at the end of Apur Sansar as Apu is holding his son on his shoulders as they head back to Calcutta.

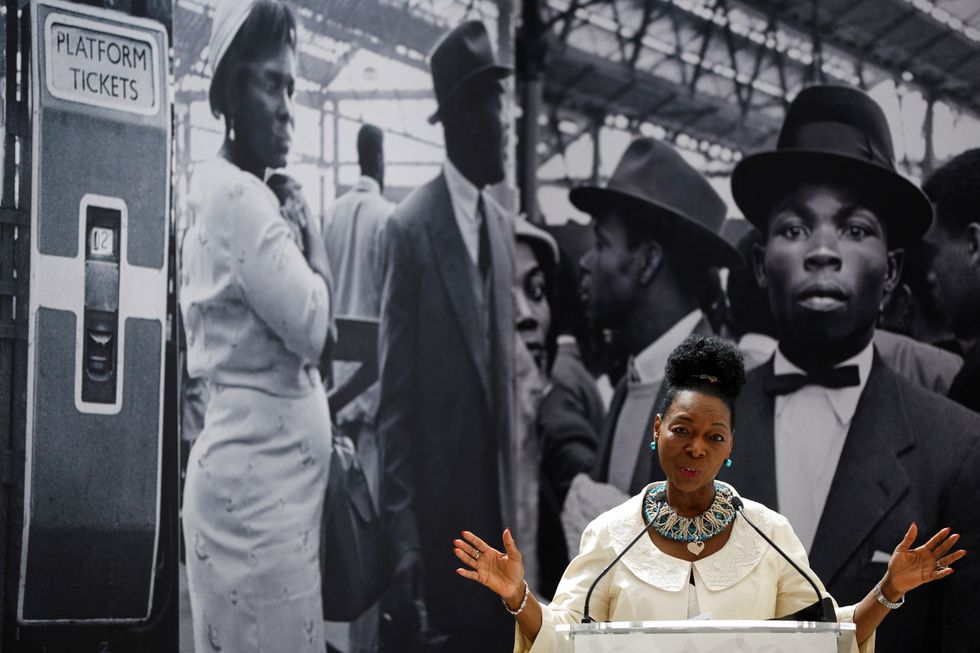

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’

Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’ Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’

Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’ Mahira Khan

Mahira Khan ‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience

‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’

Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’  John Abraham

John Abraham Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal

Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal  Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut

Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut Sana Yousuf

Sana Yousuf