RACISM remains deeply entrenched in the NHS, shaping the experiences of both staff and patients from minority backgrounds, an Asian author has said.

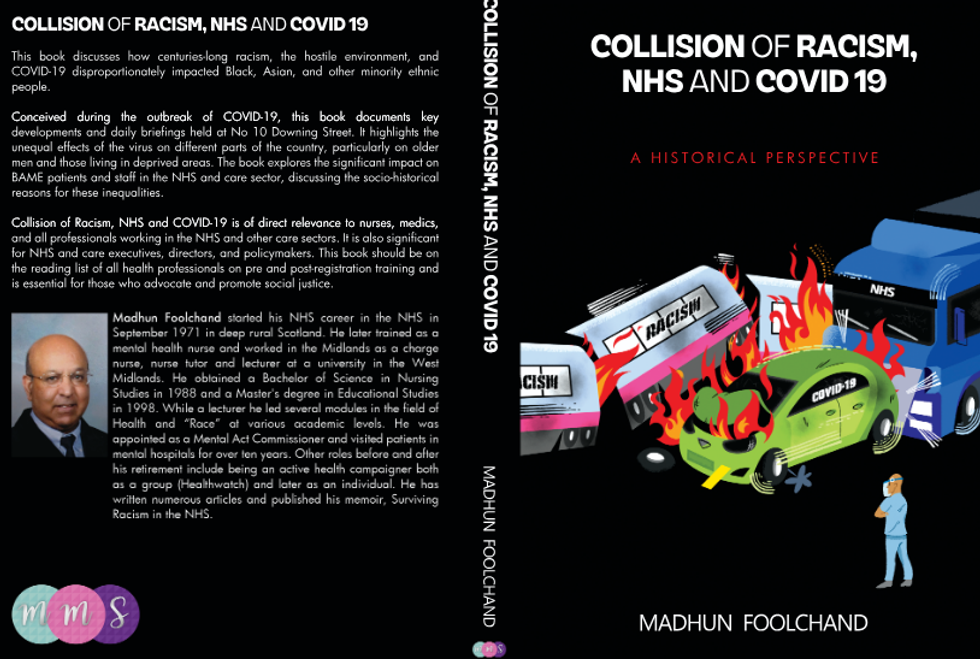

Madhun Foolchand’s new book, Collision of Racism, NHS and Covid-19: A Historical Perspective, examines how black, Asian and minority ethnic patients and staff have faced disproportionate suffering, neglect, and loss within the NHS.

Launched at Wolverhampton Art Gallery on October 4, as part of Black History Month, the book is both a personal testimony and a broader historical examination of racism in the NHS.

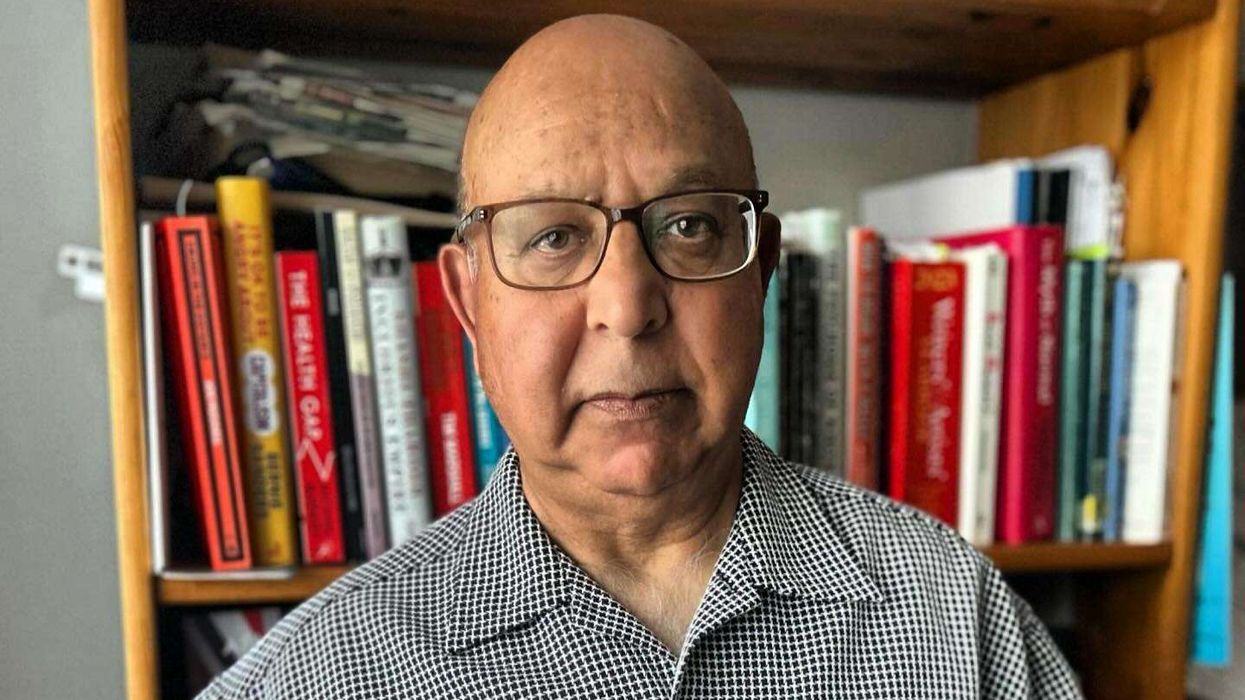

Foolchand, a former nurse and tutor, told Eastern Eye, “The main reason I wrote this book was to speak up for NHS staff who face harassment and bullying, but cannot voice their experiences openly.

“Speaking out often exposes them to further harassment, bullying, and discrimination. I wanted to stand up for those who cannot speak for themselves while they continue working within the NHS.”

Foolchand, 75, whose grandparents migrated from Gujarat to Mauritius, has drawn on more than four decades of NHS service to lay bare the depth of systemic inequality in the health service.

He said, “The NHS is a mirror of society. Whatever values and hierarchies exist in society are absorbed into the NHS. And, unfortunately, much of this is rooted in white superiority.”

Foolchand began his career in September 1971 in rural Scotland. He later trained as a mental health nurse and worked in the Midlands and was a nurse tutor and lecturer at a university in the West Midlands. He has led university modules on health and race and previously served as a Mental Health Act Commissioner.

Since retiring, he has campaigned for equality and accountability in healthcare.

“Even though local communities were poor themselves, there was a deeply ingrained sense of hierarchy. People believed they were better than those from India, Mauritius or the West Indies,” he recalled. His career exposed him to persistent structural inequalities: black and Asian staff stuck in low-skill roles, denied promotion opportunities and channelled into less prestigious specialisms, such as mental health or elderly care.

“When I worked in Glasgow, mental health hospitals were full of Asian doctors,” he said. “Yet in general hospitals, 99 per cent of staff were white. This was not accidental. It was a form of institutional racism.”

The idea for the book began during the Covid-19 pandemic. Foolchand started keeping notes during Downing Street press conferences, aware that the crisis would expose deep inequalities. He said the pandemic proved his point. “Black, Asian and minority ethnic staff and patients suffered disproportionately during Covid-19. This was not simply bad luck; it reflected systemic failures in the NHS.”

One was the distribution of personal protective equipment (PPE). “Much of the PPE was designed for a white face model. It didn’t fit people who wore turbans, head veils, or had beards. That placed them at greater risk,” he said.

He reiterated what Eastern Eye reported during the pandemic – that overseas doctors, who formed a significant part of frontline staff, were often pressured to work with Covid patients and discouraged from speaking out.

“If they raised concerns, they risked their references, their training opportunities, even their visas. So many stayed silent. And tragically, many paid the price with their lives. At the height of the first wave, a memorial service in London remembered around fifty black and Asian GPs who died caring for patients,” he said.

Foolchand’s book traces racism in the NHS back to its creation in 1948, placing it in a broader historical and colonial context. He explores the history of his own family, that of colonialism in India and Africa, and the contribution of Asian and African soldiers in both world wars.

He recalled how millions of soldiers from the subcontinent and the Commonwea l t h fought alongside the British in both wars. “They faced segregation, lower pay, assault, and dismissal after the wars. When the NHS was created, racism was already embedded in society. That toxic environment has persisted,” Foolchand said.

He compared the treatment of Caribbean and Asian migrants with that of Polish migrants after the second World War. The Polish Resettlement Act of 1947 gave housing, employment and education to thousands of Polish people who could not return home.

But similar rights were denied to those arriving from the Caribbean or India.

Foolchand said the NHS must acknowledge the role of non-white staff and be held accountable for biased attitudes. He added, “Policies to address racism already exist, but they are rarely implemented. Senior managers must be held accountable. Race equality measures must be part of NHS performance criteria.” Representation is another crucial issue. Out of 122 NHS chief executives in England, only seven or e i g h t a r e f r o m minority backgrounds. “That means these voices are missing at the top. And without representation, decisions will not reflect the needs of all communities,” he said.

Foolchand also stressed that diversity policies need constant review. “We must ask: are they reducing discrimination? Are they improving promotion rates for black and Asian staff? Are they stopping good staff from leaving because of poor treatment?” He said individuals have a role to play too, asking them to “keep records, speak up, support each other, join trade unions”.

“These are not small acts. They are the foundation for change,” he said.

According to the author, Black History Month was the right moment to address these issues. He said, “We must document history. Many people don’t know that Asian and black soldiers fought in both world wars. History is not just about the past; it informs the present and shapes the future.”

Foolchand said tackling racism in the NHS was not as an isolated problem, rather it was part of a wider movement for justice. “Without black and Asian staff, there would be no NHS. In 1948, the service recruited heavily from India and other former colonies. If they had not done so, the NHS would have collapsed. We must remember and protect their contribution,” he said.

“This is about fairness, respect and dignity. It is about ensuring the NHS becomes a place where all staff and patients receive equal treatment.”