I GREW up in a small town in north India with an idyllic vision of England.

It was the land of Shakespeare; of Milton’s Paradise Lost; of the romantic poets Keats, Byron and Shelley; of Enid Blyton’s Famous Five having adventures on their “hols”; of Robin Hood and his merry men in green fighting the evil Sheriff of Nottingham in Sherwood Forest; of hansom cabs clattering through the cobbled streets of London on foggy nights in the Sherlock Holmes stories; of murder in Agatha Christie’s 4.50 from Paddington; and of Peter May and Colin Cowdrey driving beautifully through the covers at Lord’s.

And, to a great extent, this is the England I am happy to say I have found. If I left, I would miss the autumn leaves and carols from King’s on Christmas Eve.

But, clearly, there is a darker Britain. The Caribbean countries are demanding reparation for the crimes committed during the slave trade.

Should these reparations be made, as set out in the just-concluded Commonwealth summit in Samoa? After all, Britain demanded reparations from Germany after two world wars.

To begin, the Caribbean states want an apology.

They may have a bit of a wait. To date, Britain has not apologised for the Jallianwala Bagh massacre of 1919 in Amritsar.

To be sure, Britain has expressed regret for the wrongs of the past, but this is coupled with a wish to move on and engage constructively for the future.

King Charles with Baroness Patricia ScotlandThe line from the Foreign Office in London is: “Reparations are not on the agenda for the Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting. The government’s position has not changed – we do not pay reparations.”

However, the communiqué from 55 Commonwealth nations, including the UK and many members of its former empire, said heads of government, “noting calls for discussions on reparatory justice with regard to the transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans and chattel enslavement … agreed that the time has come for a meaningful, truthful and respectful conversation towards forging a common future based on equity”.

The prime minister, Sir Keir Starmer, is against the whole concept of reparations: “What they’re most interested in is, can we help them working with, for example, international financial institutions on the sorts of packages they need right now in relation to the challenges they’re facing?

“That’s where I’m going to put my focus – rather than what will end up being very, very long, endless discussions about reparations on the past. Of course, slavery is abhorrent to everybody; the trade and the practice, there’s no question about that. But I think from my point of view… I’d rather roll up my sleeves and work with them on the current future-facing challenges than spend a lot of time on the past.”

It is ironic that the foreign secretary, David Lammy, born in Britain to parents from Guyana, will have to go along with the prime minister, whatever his personal inclinations.

On May 19, 2007, Lammy addressed the Wilberforce Institute for the Study of Slavery and Emancipation to mark the 200th anniversary of the abolition of the slave trade.

The international conference heard that “slavery continues to blight millions of lives. The emancipation movement still has unfinished business.

“As we know, Parliament passed the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act in March 1807, an act that ended the legal trade in human cargo throughout the British Empire, and eventually led to the abolition of transatlantic slavery itself,” began Lammy.

David LammyHe went on: “Before this year, for the most part, people like myself – the descendants of enslaved peoples – have often been sidelined from the debate. But we should remember that emancipation from slavery was only the beginning of a slow, painful process, the beginning of an arduous journey out of servitude and second-class citizenship, back towards equality.

“It is perhaps time to discuss, openly and honestly, without fear of recrimination or blame, how the dismantling of language, of culture and customs, and the displacement of millions of people descended from those slaves has affected not only them, but many parts of Africa, and the world view of the continent.

“I believe that, consciously or subconsciously, this physical, spiritual and cultural separation, which has evolved over centuries, today, can and does feed into an individual’s lack of cultural identity, which in turn can lead to feelings of resentment and alienation toward, and from, this country – our home.

“It is a tragedy that this aftermath is being played out in the worst of our inner city streets of London, Manchester, Birmingham, Leeds, in constituencies such as mine in Tottenham, where a significant minority of poorly educated, disaffected black youths, usually male – despite being born in this country, despite being part of a progressive democracy and all that that provides – feel on the fringes of it.

“Why are half the black children in this country brought up in single-parent households like the one I grew up in? Why is it that there are three times as many black males in prison and mental health institutions than in tertiary education? Why are black children, and again, especially boys, almost three times more likely to be permanently excluded from school than their white counterparts?

“I do not for a moment claim that the slave trade is directly and solely responsible for these outcomes, but I do believe that the confusion of identity, the disempowerment, the overt racism and endemic poverty brought upon later generations has left many black Britons, young and old, incapable of following Bob Marley’s command to emancipate ourselves from mental slavery.”

Baroness Patricia Scotland is being succeeded as Commonwealth secretary general by Shirley Ayorkor Botchwey, the minister for foreign affairs and regional integration of Ghana, who believes in reparatory justice.

Caricom, the group of Caribbean countries pressing for reparations, have a 10-point plan.

It begins: “The descendants of the indigenous peoples subjected to genocide, the loss of several cultures, and the erasure of numerous languages require a full and formal apology. “The descendants of the enslaved African population subjected to deadly forced migration, and a system of colonialism that destroyed their bodies and their cultures, require a full and formal apology.

“Groups subjected to deceptive systems of indenture deserve a full and formal apology. All the ancestors who were destroyed or affected by colonialism, their descendants alive today, and future generations require a full and formal apology.

Shirley Ayorkor Botchwey at the summit“Only a full and formal apology can allow for the healing of wounds and the destruction of cultures caused by colonialism (enslavement and other forms of oppression of peoples).

“A full apology accepts responsibility, commits to non-repetition, and pledges to repair the harm caused. Governments from countries responsible for the destruction have refused to offer apologies and have instead issued Statements of Regret. These statements do not acknowledge that crimes have been committed and continue to represent a refusal to take responsibility.”

There are people in the UK who say British history is being trashed by leftwing historians. And the National Trust was attacked for its report which revealed nearly 100 properties in its care were built either with colonial loot from India or proceeds of the slave trade.

There has been a heated debate about Chris Kaba, the 24-year-old shot dead in 2022 by a white police officer, Sgt Martyn Blake, who was recently cleared. Kaba was raised by his Congolese parents. Was someone like him always destined to fail because of the back history of the African and Caribbean communities? More important, can the future be changed?

Financial reparations running into trillions of pounds is neither possible nor practical, but it is in Britain’s interest to help heal the wounds of history.

So, yes, a full apology should definitely be forthcoming.

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’

Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’ Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’

Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’ Mahira Khan

Mahira Khan ‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience

‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’

Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’  John Abraham

John Abraham Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal

Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal  Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut

Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut Sana Yousuf

Sana Yousuf

Shraddha Jain

Shraddha Jain Arundhati Roy

Arundhati Roy William Dalrymple and Onjali Q Rauf

William Dalrymple and Onjali Q Rauf Ravie Dubey and Sargun Mehta

Ravie Dubey and Sargun Mehta Money Back Guarantee

Money Back Guarantee Homebound

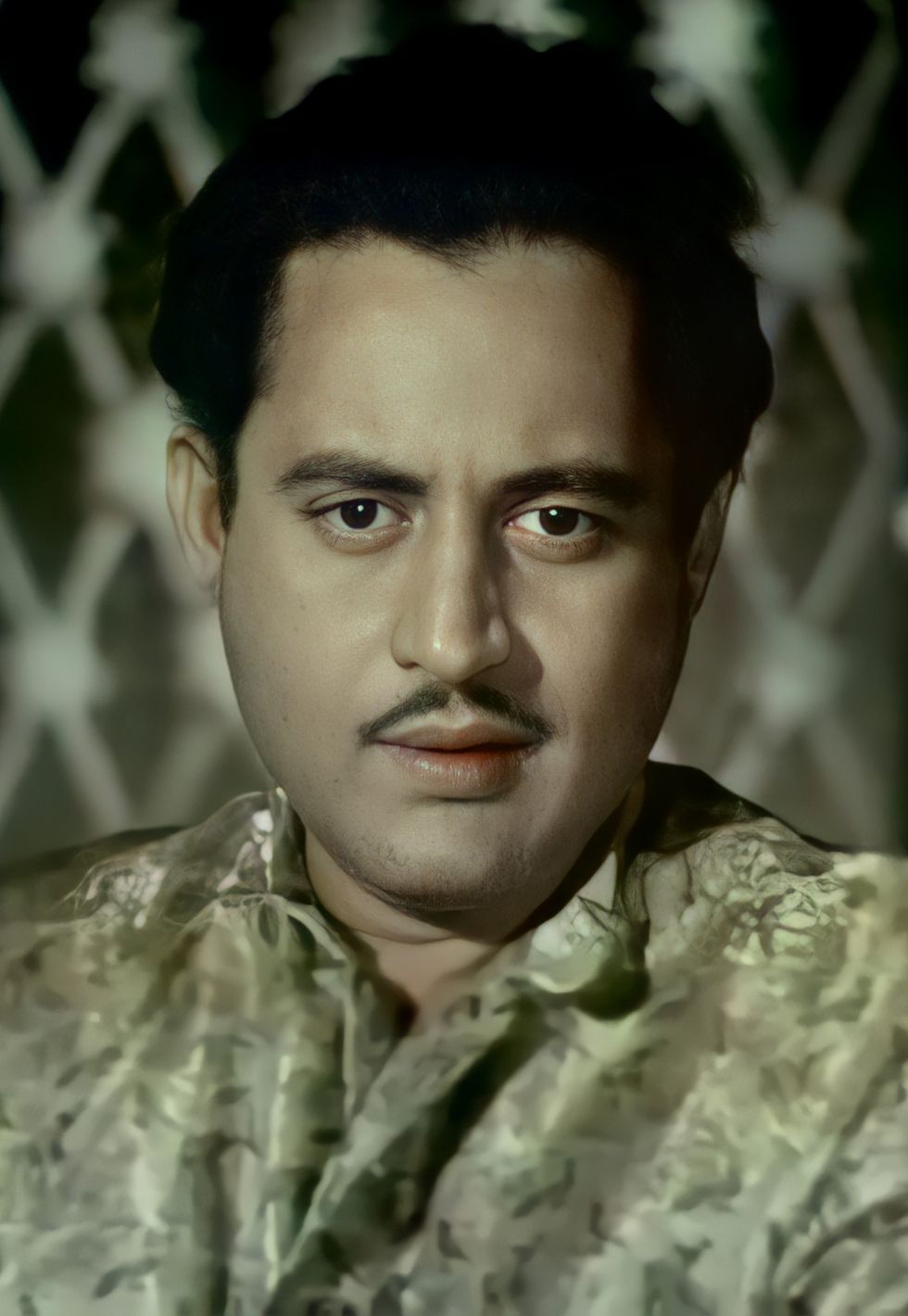

Homebound Guru Dutt in Chaudhvin Ka Chand

Guru Dutt in Chaudhvin Ka Chand Sarita Choudhury

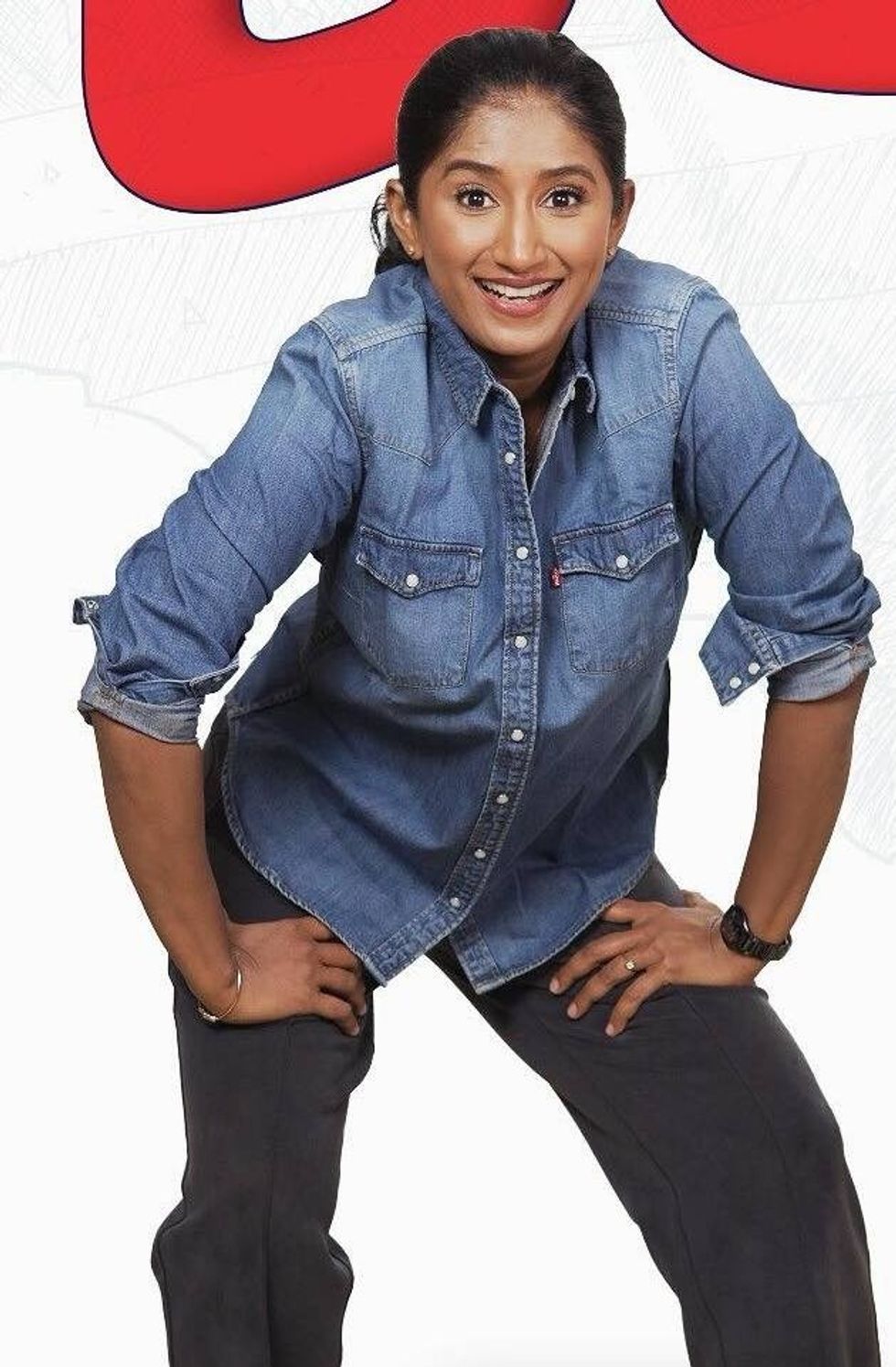

Sarita Choudhury Detective Sherdi

Detective Sherdi