by SHALINA PATEL

WHEN you see the letters UDHR, I’m sure you know what they stand for – the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

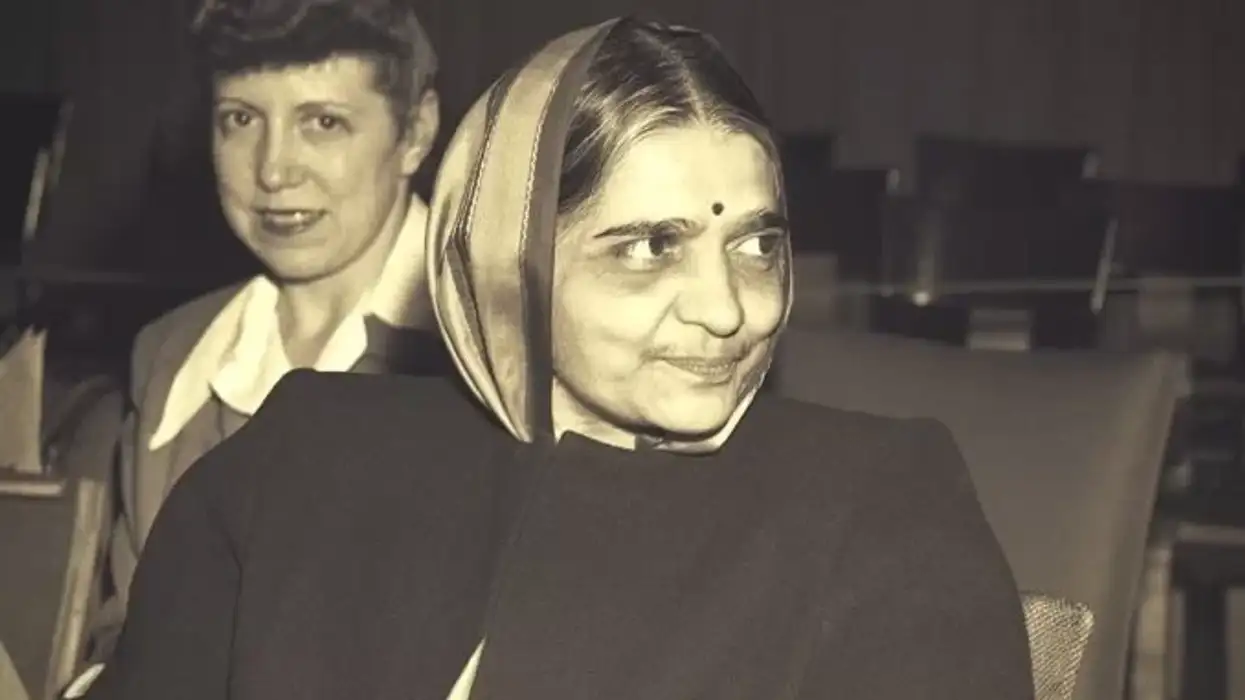

But did you know that it was an Indian reformist called Hansa Mehta who is credited with rephrasing Article 1 from ‘all men’ to ‘all human beings are born free and equal’? Without her contribution, it’s likely the document would have been called the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Man.

Born in July 1897 in Gujarat, Mehta came from a family of scholars and writers. Her interest in academics led her to study at my old university, the London School of Economics.

Mehta was influenced by Sarojini Naidu’s nationalist actions, and soon found herself actively participating in the Swadeshi and Non-cooperation movement in India, campaigns which aimed to boycott the British Raj, from cotton to taxes.

She was arrested and imprisoned for three months for protesting. Luckily the Gandhi-Irwin pact – which included the agreement to free political prisoners – cut her internment short.

When she wasn’t out protesting, she wrote several children’s books in Gujarati as well as translated many English stories, including Gulliver’s Travels.

Mehta was elected to the Bombay Legislative Council twice, first serving in 1937. She advocated for changes to the education system as well as women’s rights in India. She pushed for the abolition of child marriage and also helped to draft the Indian Women’s Charter of Rights and Duties in 1946.

She was appointed to the UN on India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s recommendation, and it was her role as the delegate for India that led to her changing the wording from men to human beings.

Mehta went on to become the vice-chairman (ironically the title then was chairman rather than just chair or chairperson) of the UN Human Rights Commission in 1950. Her later work reflected her interest in gender equality, revealed by her arguments that women should be treated as individuals rather than dependants.

Her contribution to making UDHR ‘universal’ in the truest sense, was also appreciated by the then United Nations general-secretary Ban Ki-Moon in 2015. He said, “The world can thank a daughter of India, Dr Hansa Mehta, for replacing the phrase in the UDHR.”

Mehta is, for me, a classic example of ‘hidden history.’ As someone who prides themselves on being well versed in issues of history and equality, to come across a woman of Gujarati origin, who went to the same university as me and had such an impact on such a significant part of modern history is truly fascinating.

This column is written by Shalina Patel, who is the head of teaching and learning in a large comprehensive school in north-west London. Patel runs the History Corridor on Instagram, which has more than 15,000 followers and showcases the diverse history that she teaches. She has delivered training to more than 200 school leaders since July 2020 on decolonising the curriculum. Patel won the Pearson Silver Teaching Award 2018 for Teacher of the Year in a Secondary School.