By DR SAMAR MAHMOOD

HAVING an illness and needing to consult a doctor about it is stressful. To then have to worry about how much the consultation and further treatment might cost only adds to the stress and might make the existing condition worse.

However, to have a free at the point of use health system wherein we can go and see a doctor and only have to focus on how to get better is a huge privilege. Many countries offer their citizens free healthcare in some form, but few can afford to offer a service which boasts highly-trained healthcare professionals, modern diagnostic investigations and world-class treatments.

And this is why the National Health Service is probably the greatest healthcare system in the world.

To work for such an organisation is also a privilege. It is sad then that being an employee in today’s NHS has become a major source of stress. Almost all clinical staff within the organisation have the same complaint: there is too much work to do, not enough time to do it in, not enough support or resources with which to do it, and a high risk of making errors in such undesirable working conditions.

I am a General Practitioner in the NHS and feel that I have the best job in the world. I see patients of all ages and from all walks of life. I listen to their life stories, their problems, and I learn so much from them. Above all, I am in a position where I can make real improvement to their lives.

Despite this, there is not a single day where I do not come home from work feeling stressed. My GP colleagues elsewhere in the country experience the same. Doctors are leaving the profession in droves due to burn-out.

Where is all this stress coming from? It is the relentless high pressure of the job – both in terms of workload and work complexity. In a typical working day I can see in excess of forty patients (that doesn’t include home visits), all of whom get just a short consultation. It is impossible to manage complex health issues within 10 minutes, and the scope for making mistakes is high.

My working day doesn’t end when I leave the surgery, however. Once home, I must process dozens of blood test results, prescriptions and general admin ready for the next day.

The situation is no better in hospitals. Nurses are notoriously too busy to take even natural breaks, which is clearly unhealthy; consultants are made to perform elective procedures on their weekends off, just to reduce waiting list times; junior doctors are suffering pay-cuts but made to work more unsociable hours.

What is obvious is that the physical and mental health of NHS staff is being adversely affected.

It comes as no surprise then that there is a recruitment crisis in almost all clinical areas of the NHS.

The solution is not straightforward and perhaps a discussion for another time, but briefly: government funding into the NHS is at a record high, but we need more. It is a two-way street, however.

As a nation, we also need to respect the healthcare system and use it appropriately; yes, we are tax-paying citizens and are entitled to use it, but we also pay car insurance and only make a claim for major problems. Could we not utilise the NHS in the same way and reserve it only for major or un-resolving health issues?

Unfortunately, there is no quick remedy for the improvement of NHS staff morale and wellbeing. For now, we are likely to see increasing numbers of health professionals absent from work on ill health grounds – a critical situation in which doctors are becoming patients.

Follow Dr Samar Mahmood on @thisissamar

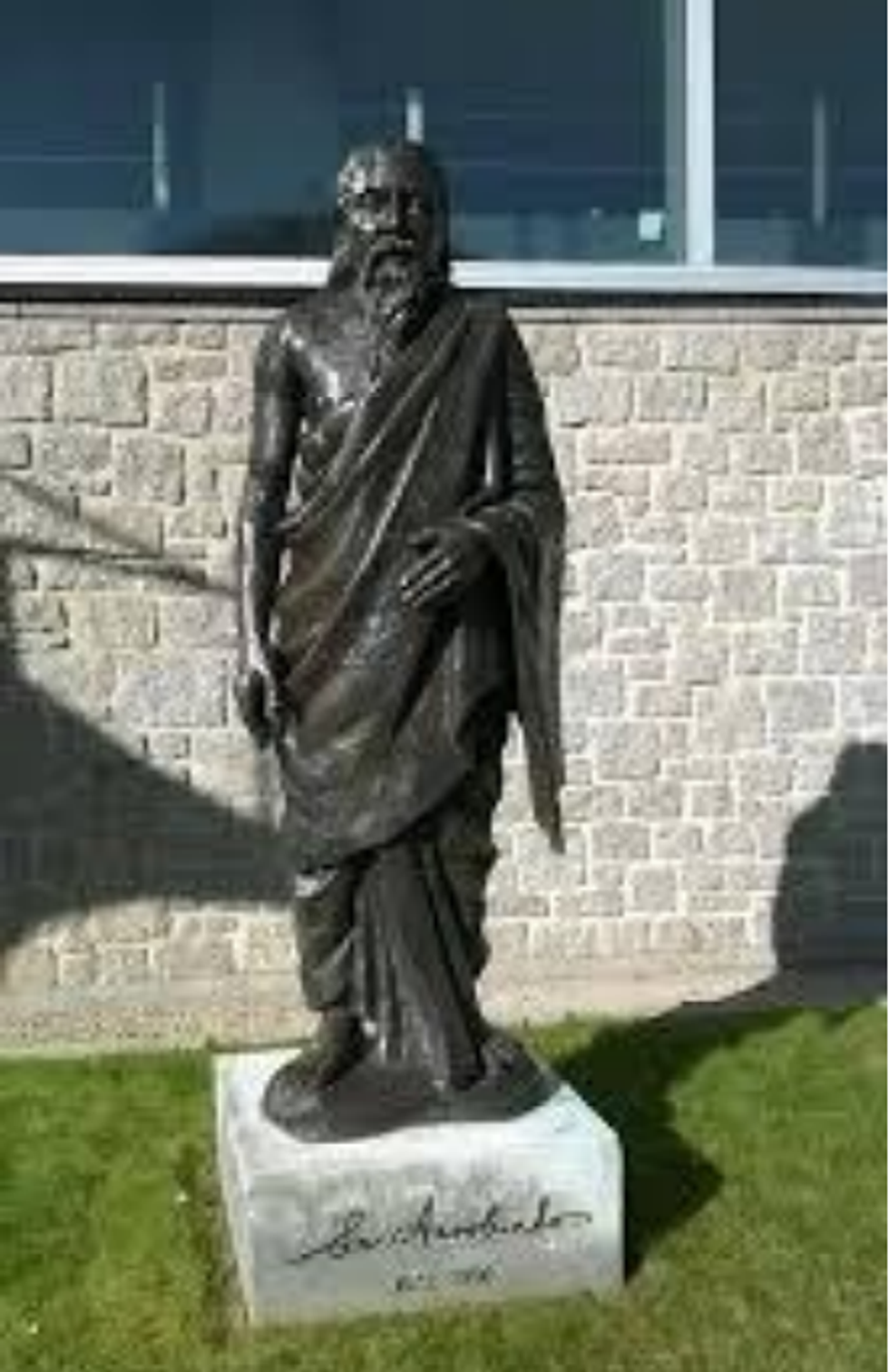

Heehs describes two principal approaches to biographyAMG

Heehs describes two principal approaches to biographyAMG

David Beckham wearing a David Austin Roses "King's Rose" speaks with King Charles III during a visit to the RHS Chelsea Flower Show at Royal Hospital Chelsea on May 20, 2025Getty Images

David Beckham wearing a David Austin Roses "King's Rose" speaks with King Charles III during a visit to the RHS Chelsea Flower Show at Royal Hospital Chelsea on May 20, 2025Getty Images

GP reveals stress within the NHS