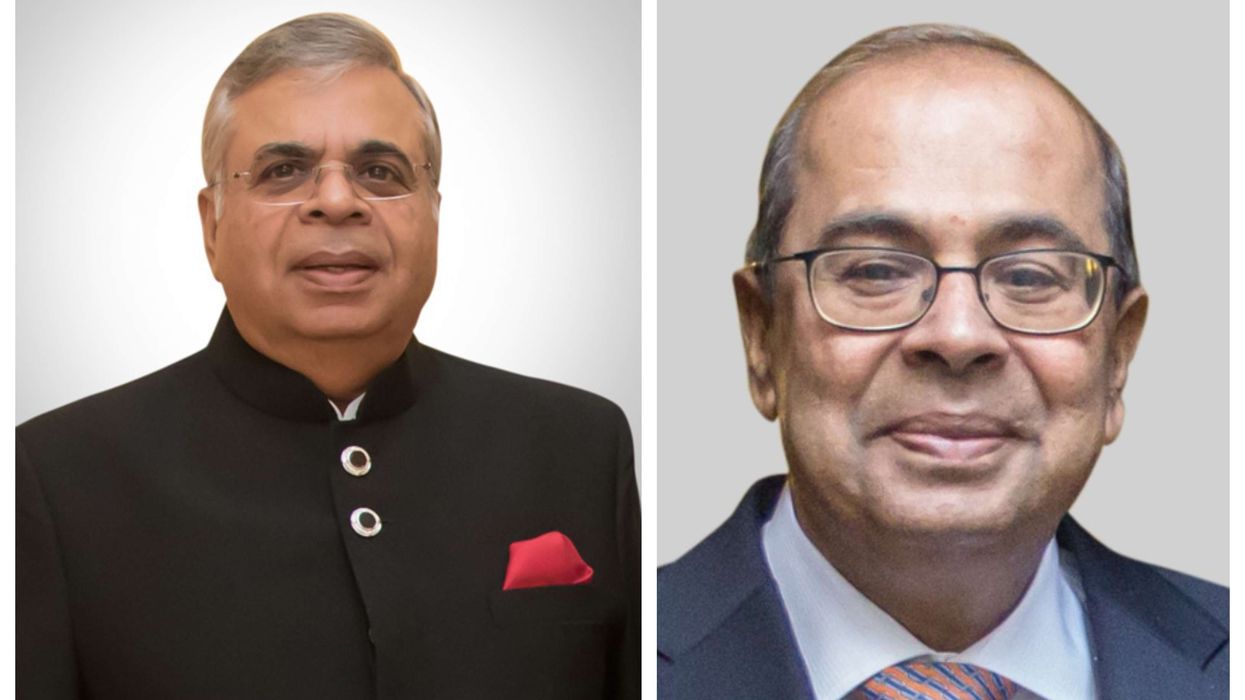

SINCE the start of the pandemic, Dr Chaand Nagpaul, chair of the British Medical Association (BMA) council, reckons he has given well over a hundred interviews, dealing with “PPE, test and trace, the public health dimension, and BAME issues”.

He has regular meetings with the health secretary Matt Hancock and other senior figures dealing with the Covid crisis.

“The BMA is a very, very English organisation, steeped in history, founded in 1832, with a beautiful Lutyens building,” he says. “It didn’t even cross my mind that I would be in the BMA. I would never in my wildest dreams have thought that I would end up as the head of the nation’s doctors.”

He now always makes sure he is thoroughly briefed. An early lesson he learnt as an Indian was to try and be better than the competition.

The story of how he got to the position he now occupies at the pinnacle of the British Medical Association is

a remarkable and inspiring one – and testament to the Asian migrant spirit, especially as he had faced “nine rejections in a row and not even been called for an interview” when first applying for a GP training scheme. “Getting through the door” was crossing the first barrier. And it wasonly by chance that he spoke at a BMA national conference in1990 as a young doctor.

“I was petrified going up on stage to speak to 500 people,” he remembers. “There was a set of health reforms in this country. And I was very excited about some of those changes. I passionately said what I thought was wrong with the government policy – and there was a huge applause. The Evening Standard covered it and the next thing I knew people were calling on me to be involved in the BMA. And then I did so.”

That proved a turning point.

“I stood for election on the national BMA GPs’ committee in 1996. That’s how I got into the BMA. I progressed and became a member of their executive in 2007, the first non-white to be a member of the executive.”

He was chair of the GPs’ committee from 2013-2017, again the first non-white, and awarded a CBE in 2015 for services to primary care. The BMA represents 160,000 doctors across the UK, with a significant proportion from the ethnic minorities.

“As chair of council, I am representing GPs, junior doctors, medical students, public health doctors, academic medical managers, every category of doctor.”

Nagpaul was elected chair of the BMA council in June 2017 for a three-year term when he replaced Dr Mark Porter.

“I was the first non-white chair in 180 years. I have had to break many glass ceilings. But the BMA is now more diverse than at any time during my career. I concluded my three years in June 2020, and was re-elected for a further year without challenge.”

That means he has had to provide leadership during the pandemic.

“I have a final year option if I want to stand for which I could be challenged.”

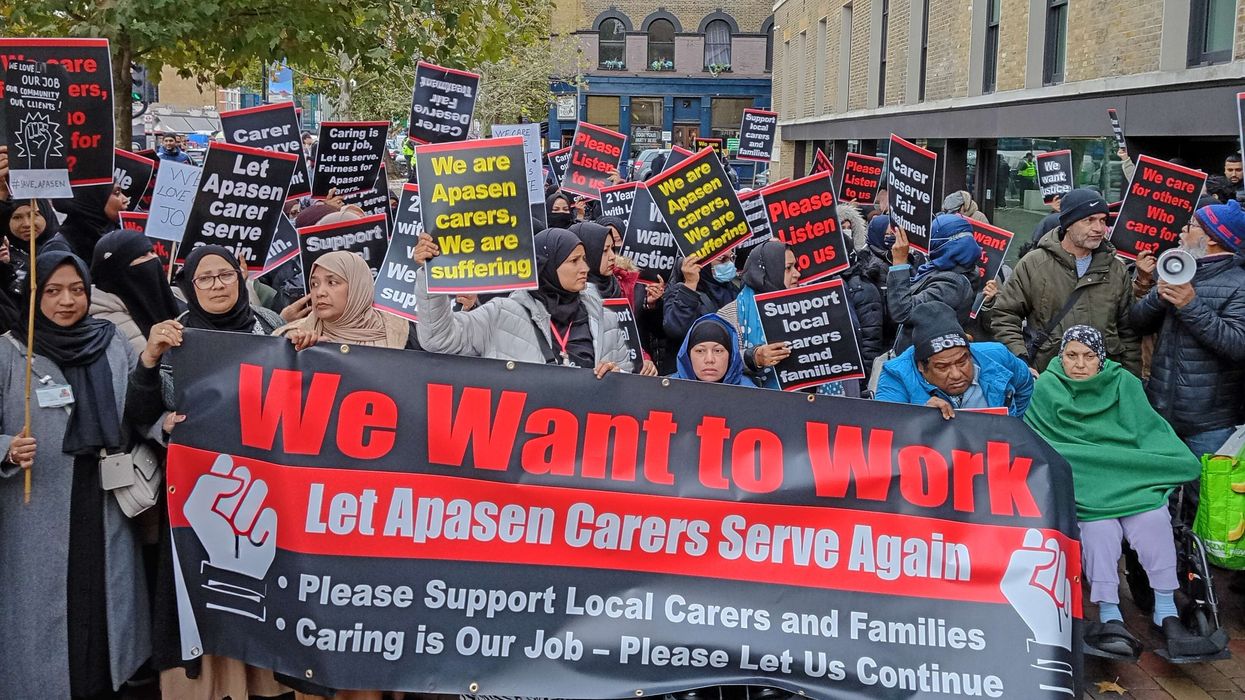

The Covid death toll in the black and Asian communities has been disproportionately high. This is why he has pressed the government to make its safety recommendations “culturally sensitive”, pointing out that “the

messaging from the government has been very difficult to understand, even for the indigenous population, let alone the ethnic minorities”.

“There’s just no doubt that Covid has highlighted many of the issues that I had raised before. The race issues were going to be one part of my job. I did feel a sense of responsibility and duty to make sure that the BMA represented the black and ethnic minority doctors in the UK as best as it could because I actually knew they suffer much more adverse experiences in the NHS. I wanted to make sure that changed during my tenure.”

Chaand was born in Nairobi, Kenya, on February 2, 1961, to Lalit and Sarla Nagpaul, into a Hindu Punjabi family.

“My father settled in East Africa – his grandfather went there (from India), I don’t know when. My dad was a businessman who owned many petrol stations, and also had a photography business.”

Nagpaul was seven when the family arrived in London just before the great Indian exodus from East Africa. His childhood memories are of Africa being “warm and friendly. I remember thinking what on earth have my parents done bringing me to this cold and desolate place. We spent a year in south London in Clapham, which in those days was not a very attractive place. We moved to Finchley in north London. My father worked in insurance with Prudential and through his hard efforts built up a property business. I went to primary

school in Finchley, and then to Christ’s College, a grammar school in Finchley Central. I remember vividly there were people called “skinheads” and ‘Paki’ bashing.

“My father couldn’t pursue education himself because he had to look after his brothers, as in many Indian families. But he wanted me and my sister Seema to pursue academic careers.”

Today, brother and sister are GPs. His parents, now in their 80s, have stayed in the same house in Woodside Park, where once the Nagpauls were the only Indian family on the street. Young Chaand knew a boy called John Bercow, the future speaker of the Commons.

For his parents, social life revolved partly around the Hindu Cultural Centre, which still has a large photograph of Margaret Thatcher inaugurating the venue as the local MP since 1959. She enjoyed a great deal

of support from East African Asians in Finchley.

“One thing I did was work very, very hard at school. I got the best possible O and A level grades. I wanted to do medicine at university. I was always taken by science. I find it very stimulating and logical. There is scientific inquiry and a sense of justice and doing good. The two things made medicine a perfect combination.”

Nagpaul feels lucky his friends were equally aspirational Jewish pupils. “I had a real exposure to another community. I remember going to three Bar Mitzvahs.”

A new world opened up in 1979 when he opted for St Bartholomew’s Hospital Medical College, an elite institution founded in 1123 and located in the City of London. “They didn’t have very many non-white students. I experienced English culture and mixing with students from all parts of the country, many with

high class English backgrounds. I saw how other people lived in rural areas. I would sometimes visit them in their family home.”

Nagpaul got his MBBS in 1985 with full GMC registration in 1986 – and then he hit a road block despite his brilliant academic credentials. “When I wanted to do my GP training, I basically got nine rejections in a row.

Not even to get an interview was something I couldn’t understand.”

Someone explained the problem to him: “It’s your name.”

His response was: “It didn’t strike me that my name would be a barrier.”

“On my 10th application, I went to Charing Cross Hospital. And I knocked on the door of the A&E consultant. He was the postgraduate Dean. I said, ‘You don’t know me. I’m giving you my CV, I’m going to be applying for the GP training scheme here. I really would love to be a GP. I want to be part of your course.’ I was shortlisted for an interview. I was one of two out of 180 people who were offered a place. Once I got through the door, it wasn’t such a problem. It was getting past that first door. I don’t know if it would happen now. But that was the way it was then.”

His first job as a GP was with a practice in Stanmore in north-west London run by two women. He is still there 31 years later, though these days he can only spend Monday and Fridayevenings at the greatly expanded and “bespoke medical centre” because of his BMA commitments. The practice, now run by his wife, Meena, also a GP, has 14,500 patients, compared to 5,400 when he began. Entire families have grown up under his care. The Nagpauls have a daughter – a fourth year medical student training at Liverpool but currently doing an intercollegiate year at King’s College London – and a son who is studying philosophy, politics and economics at University College London.

Coming to the present, Nagpaul will continue to strive to create a level-playing field for BAME doctors.

“Sadly, in the NHS, there is plenty of evidence that the experience of BAME doctors is not equal,” he says. “We know that in terms of career progression, the higher you climb up theladder, the fewer is the number of BAME doctors. The chances of a BAME doctor being shortlisted for a consultant’s position is lower than for a white counterpart. So you’ve got far greater numbers of black and ethnic minority doctors who end up in what’s called a staff and associate specialist grade which is a sub-consultant grade. Fewer become consultants and

that leads to an ethnicity pay gap.” There are other inequalities. “You will find that black and Asian minority doctors do less well in postgraduate exams than their white counterparts. When they’ve actually looked at

this, it’s not usually lack of ability; one problem is the exams are not culturally sensitive.

“Remember ethnic minority professionals are running Google, running Microsoft. They’re entrepreneurs; they are successful in every other walk of life. So why would they not be successful in medicine? It’s because of the environment. Black and ethnic minority doctors report bullying and harassment at twice the rate as their white counterparts. They are twice as likely to be scared to raise safety concerns because they are worried about being blamed rather than the systemic factor being identified. They feel it may jeopardise their career so they don’t challenge it when they’re bullied or harassed. That takes a toll on their mental wellbeing.”

Another problem, Nagpaul points out, is that “they’re referred by the General Medical Council for disciplinary measures at twice the rate of white doctors. When you look at that in more detail, you realise it isn’t because they’re worse doctors, but there is an inbuilt bias against them. They’re not as well able to stand up for themselves because they already feel intimidated – whereas someone else might be able to challenge the

policy if they’re accused of wrongdoing.”

He says he has “met a lot of GPs who have been here for decades. They have taken on jobs no one else would. They slug their guts out and receive no recognition for what they provided. I meet hospital doctors who in years gone by have gone to Blackburn and Bury and places no house officer wanted to go to, doing jobs and rotas no one else wanted. These people are highly capable, but the system didn’t support them. As a GP, I can say I was more articulate, I was schooled here, trained here. But they didn’t get the same look in.

“They weren’t given the funding to develop their premises. They probably didn’t have the savviness and even know how to apply. And then when anything went wrong, gosh, they got the full weight of regulatory criticism. This needs to be corrected. Thy have toiled and given their lives to the NHS.

“When you look at Care Quality Commission inspections, they will rate Asian doctors, working alone, at a far worse level than others. When the CQC kit comes to a practice, you do a presentation. If you’re a larger practice, you’re pretty savvy and know how to sell the package. But if you’re literally one or two doctors and struggling just to run a practice, will you able to put forward a power point slide and all that? There is inequality in the system and it doesn’t bring out the best in our workforce. It doesn’t allow the NHS to utilise the full potential of its workforce, because many of these doctors could do so much more given the opportunity.”

What next?

Nagpaul, who is reading A J Cronin’s The Citadel, hasn’t forgotten why he chose to study medicine all those years ago: “I want to carry on seeing some of the patients I know and being a GP, I do believe that the NHS is a unique and special system where people without any ability to pay can be assured of care. I am missing being a GP in the way I was.”