by Jaswant Narwal

WHEN I was eight years old, the local shopkeeper’s daughter – who was around 13 – went ‘on holiday’ and didn’t return for two years. She came back as a wife. This memory has never left me. Stories like this are too common even in our free and democratic society and in 2020, we must not turn the other cheek.

To start, we need to be honest and open about the scale of forced marriages in the UK and tackle it head on. Like many, I am shocked that they continue to occur. They were criminalised in England and Wales in 2014, yet they continue to ruin lives.

I was born in the UK to first generation immigrants from Punjab. My parents had an arranged marriage, as have other members of my family, and I have no issue with that practice. When a marriage is consensual, it can be happy and successful.

As a child, I always loved attending weddings, which were big family affairs full of splendour. But as I grew older, I realised that at some of these apparently joyful occasions there were signs of something more sinister in the background.

It was not always obvious at first, but within some patriarchal family set ups, there had been elements of ‘persuasion’, and ultimately a young woman was coerced, so was not freely giving consent. Of course, we must not forget that there are also many male victims of forced marriage.

Confronting the continuing issue is a difficult challenge, but one way is maybe through the criminal justice system. I see these cases in my role as a prosecutor, and they can be complex and difficult to investigate and prosecute.

The first issue the justice system faces is the serious underreporting of cases, so we are barely able to scratch the surface of the problem in terms of scale.

Victims don’t want to get their family members in trouble and so will not report to the police. There are feelings of loyalty, fear and shame, which can prevent victims or bystanders from coming forward, not to mention ignorance of the law.

When these crimes are reported, the cases can be complicated because they often involve young and vulnerable victims; they happen within familial settings and tight-knit communities, and sometimes the marriage takes place abroad at which point issues of jurisdiction may come into play.

I completely recognise why it can be difficult for victims to come forward, and support a case through to prosecution. I understand how it may feel isolating and scary. But I would encourage anyone who is a victim or has knowledge of a forced marriage to come forward and report it. You will be supported and whenever the legal test is met, our prosecutors will bring charges at the most serious level they can, no matter how challenging the case.

In my role as CPS lead on these offences, I visit refuges and meet victims in person. I see such sadness in these settings, and it will never leave me, but nor will the resilience and bravery of the women I meet. They inspire me to speak up and keep challenging these crimes.

To end the practice of forced marriage, we all need to take action whenever we see its pernicious signs. We need to face up to uncomfortable truths when we may recognise it among people we know and respect. We need to educate. Let us all speak out and challenge this horrific crime whenever we encounter it.

Jaswant Narwal is the Chief Crown Prosecutor for CPS Thames and Chiltern. She is also the CPS national lead for Forced Marriage, FGM, and So-Called Honour Based Abuse offences.

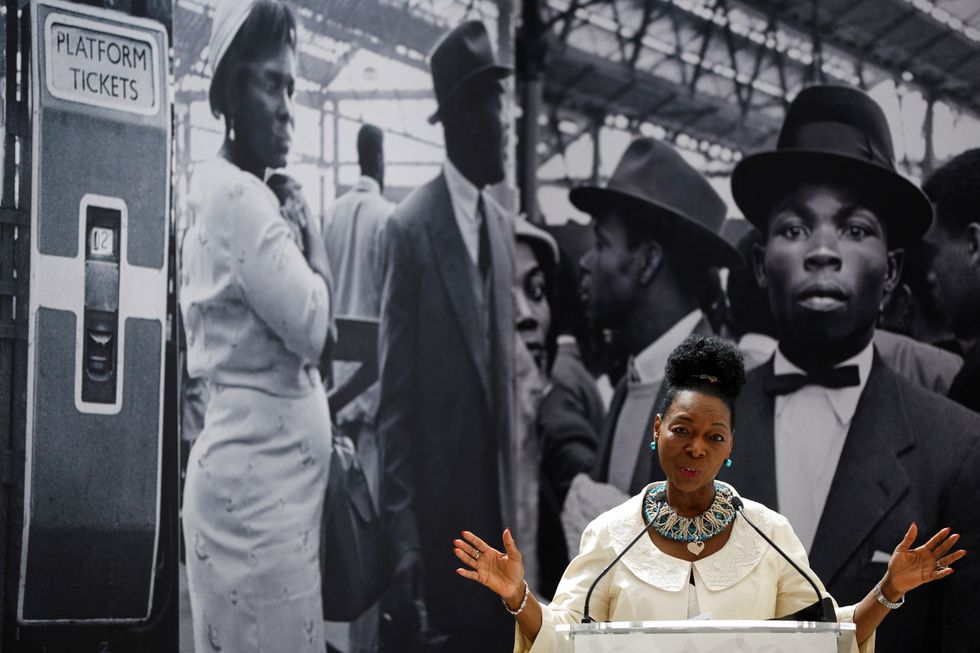

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’

Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’ Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’

Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’ Mahira Khan

Mahira Khan ‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience

‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’

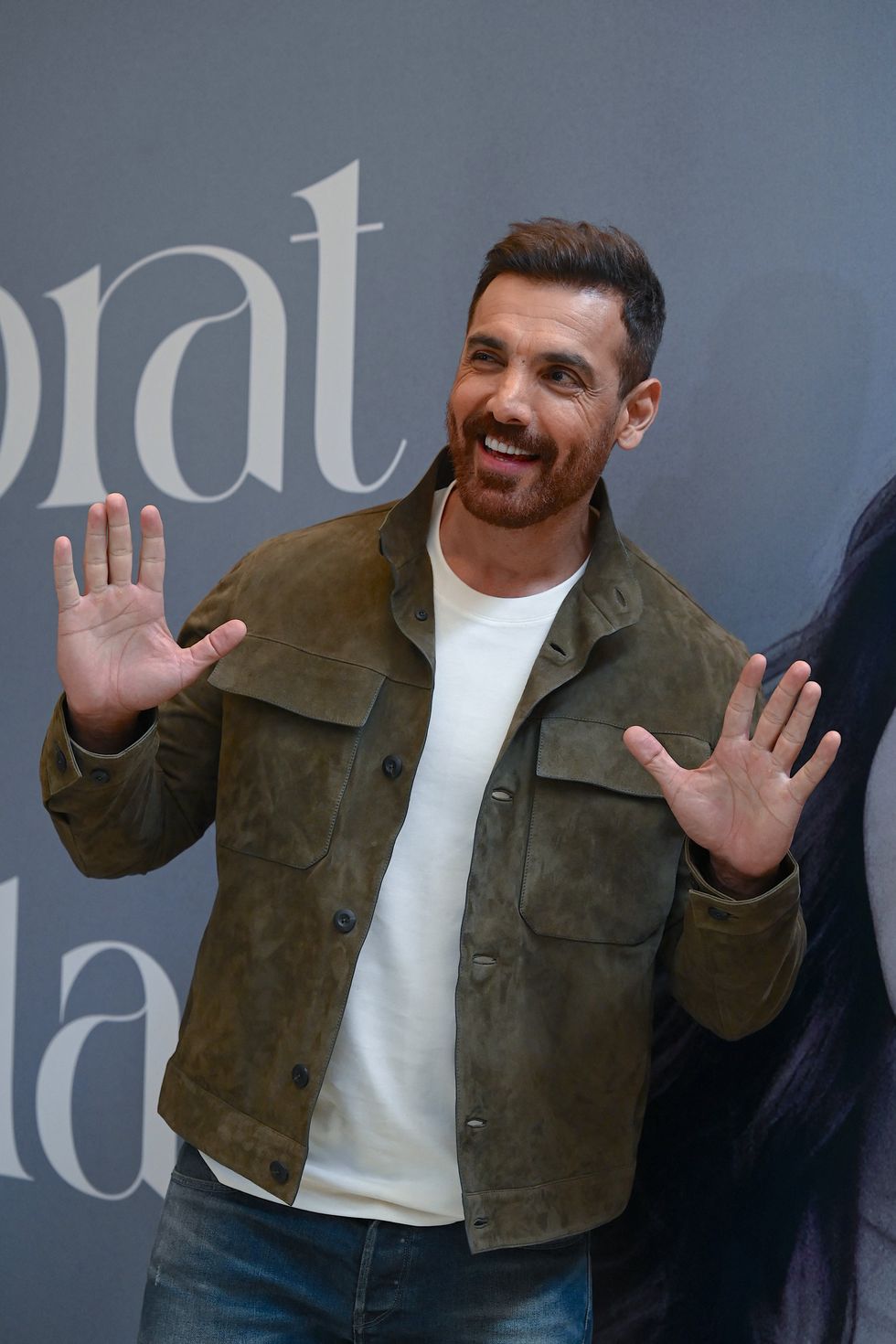

Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’  John Abraham

John Abraham Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal

Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal  Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut

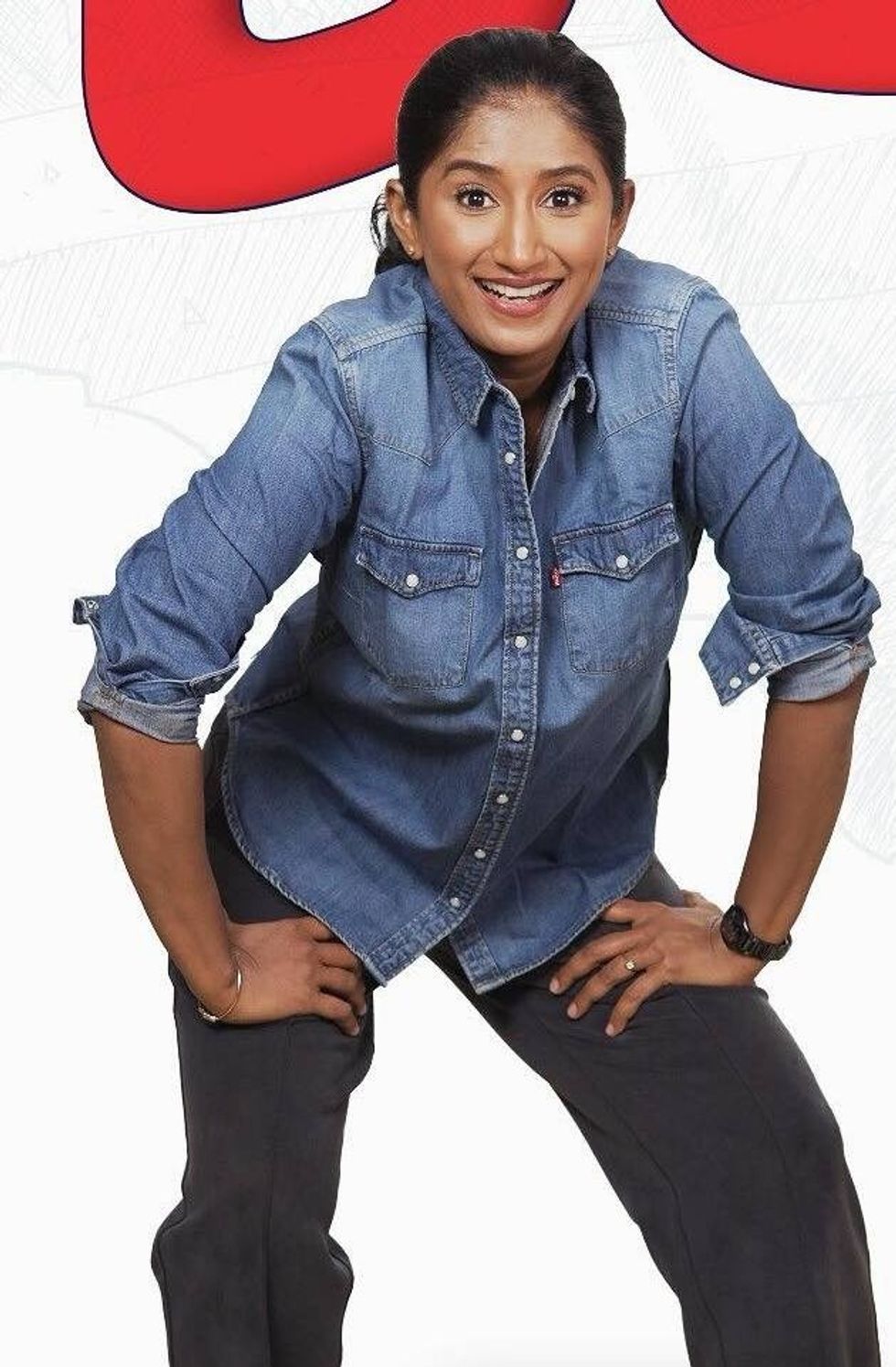

Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut Sana Yousuf

Sana Yousuf

Shraddha Jain

Shraddha Jain Arundhati Roy

Arundhati Roy William Dalrymple and Onjali Q Rauf

William Dalrymple and Onjali Q Rauf Ravie Dubey and Sargun Mehta

Ravie Dubey and Sargun Mehta Money Back Guarantee

Money Back Guarantee Homebound

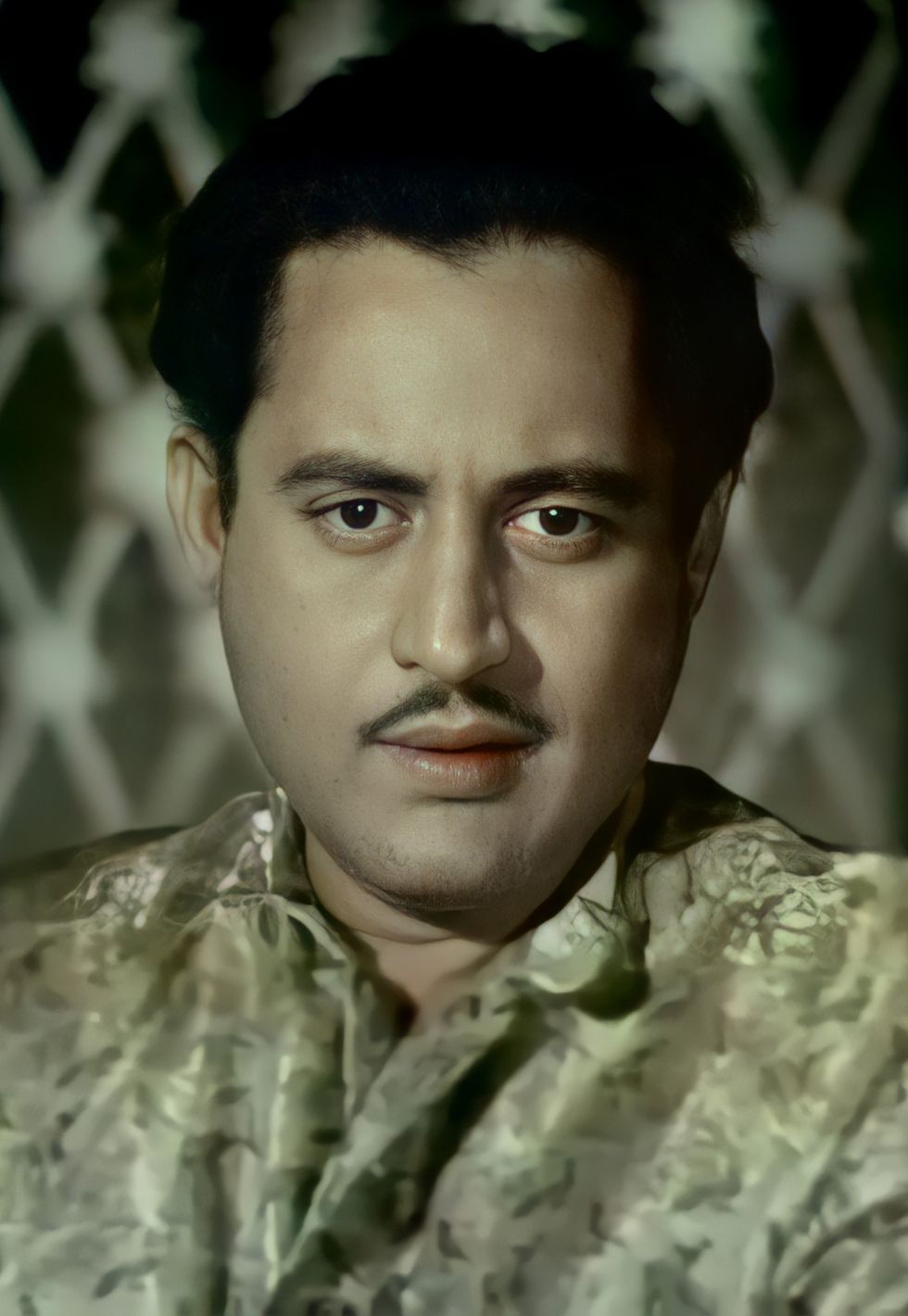

Homebound Guru Dutt in Chaudhvin Ka Chand

Guru Dutt in Chaudhvin Ka Chand Sarita Choudhury

Sarita Choudhury Detective Sherdi

Detective Sherdi