by LAUREN CODLING

ASIAN communities need tailored and culturally sensitive support services to tackle mental health issues, doctors have said, as studies showed how the pandemic has led to a surge in those seeking help.

In December, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) said ethnic groups suffered a “triple whammy of threats” to their mental health, incomes and life expectancy that left them more vulnerable to the pandemic. The mental health of BAME workers had suffered most during the outbreak, ONS data revealed.

A separate UK Household Longitudinal Study (UKHLS) analysis found that the mental health of men from ethnic minority backgrounds had been among the worst hit by the coronavirus crisis.

“Research from the Synergi Collaborative Centre shows that people from a BAME background are not treated the same as white people, so they have a higher rate of bipolar disorder, higher rate of schizophrenia and a higher rate of depression,” senior consultant psychiatrist Dr JS Bamrah told Eastern Eye. “And yet, access to health services is poor for them. If they don’t have access to healthcare, how are they going to get treatment?”

Last summer, the charity Mind confirmed that existing inequalities in housing, employment, finances and other issues had a greater impact on the mental health of people from ethnic groups compared to white people during the pandemic. And research published by the Resolution Foundation in November revealed that ethnic minority workers are more likely to be made unemployed post-furlough.

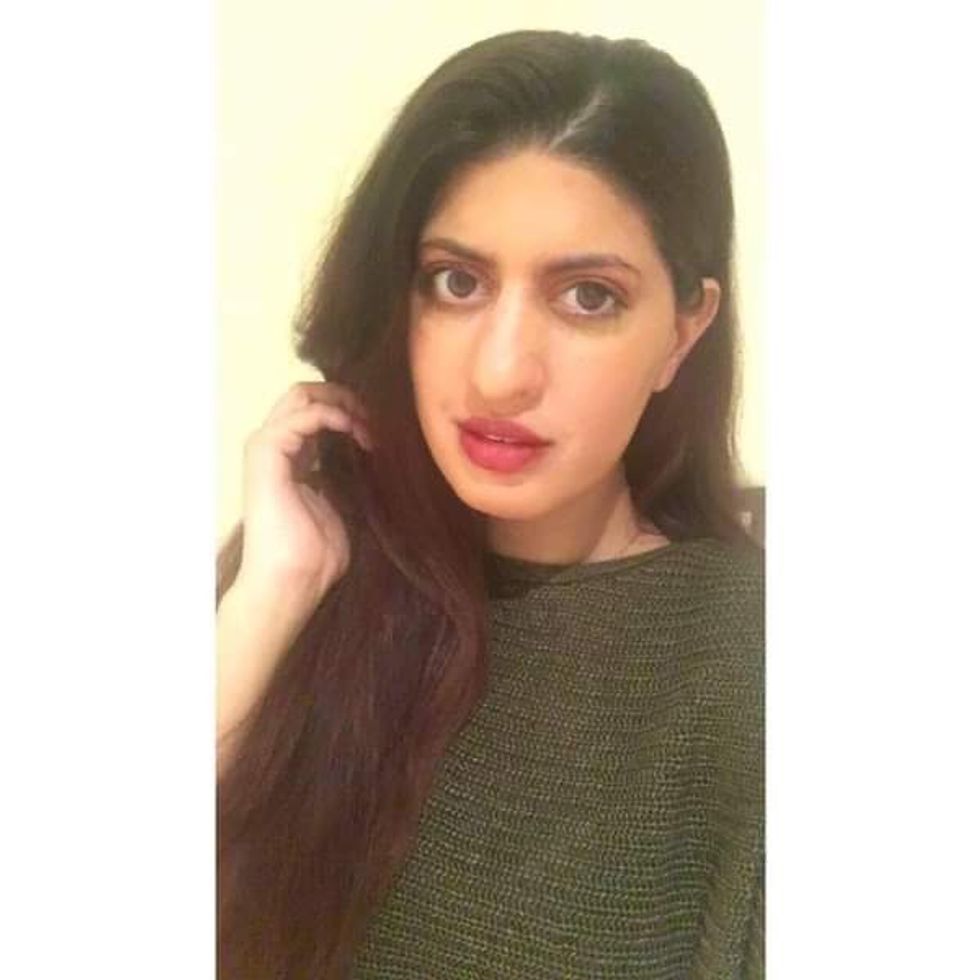

Alizeh Latif, 27, revealed her struggle with some aspects of her mental health during the pandemic. Currently on furlough from both her job as a substitute teacher and a part-time position at a bakery, Latif said she experienced extended periods of panic and anxiety. “I had anxiety prior to the pandemic, but it has gotten worse since the outbreak,” she said. “Sometimes, I get really bad chest pains if I get too panicky about things. I worry that there’s no direction in my life, that kind of thing. I over think too much but I’m trying to control it.”

Her family are currently living in Pakistan. Although she stayed with them when the outbreak began in March last year, she returned to London in July. She lives by herself and told Eastern Eye: “When the lockdown happened earlier this month, I just felt really isolated. I have some cousins (in the UK) but I can’t see them. I just want to be with my family in Pakistan.”

Her comments come as medical experts stressed the need for culturally sensitive services aimed at the community, where there is stigma around mental health issues.

Until recently, Dr Bamrah was a medical director at the Manchester Mental Health and Social Care Trust. When the trust was set up and decided on a name, some ethnic patients expressed their distaste at the choice. “(My patients) were saying, ‘we don’t want to go to a mental trust’,” he recalled. “They have a lot of preconceived notions about mental health.”

In addition, lockdown restrictions mean that mixing between households is banned. This has had an adverse impact on Asian families who rely on this sort of typical support system, some said. According to Dr Bamrah, the prevailing rules could cause distress to those who are more likely to have had the support of their family and local community.

“For a lot of Asians, a place of worship has a communal feeling to it,” he noted. “It’s not just a place of religious worship – it’s also a place where they meet their family and friends and that’s been cut off from them.”

Experts said there were a number of reasons why the mental health of Asians could be exacerbated during the pandemic. For instance, the concern about the disproportionate impact of the virus on ethnic minorities could be a contributing factor. Data has shown there is a higher number of infection rates and an elevated risk of death within ethnic groups. Psychiatrist Professor Dinesh Bhugra said: “The likelihood of knowing someone who has the infection or died due to it is higher [among Asians], and inability to mourn may add to stress.”

Shivs Ahuja*, 27, is a student from north London. She has experienced anxiety and increased stress during the pandemic. She described her worry especially for her parents as they are in their 50s. “It’s been upsetting to hear how bad (the death rate) is in the Asian community,” she told Eastern Eye. Her job prospects are worrisome, too. “I’m graduating soon, and it seems like everyone’s being made redundant,” she said. “Like all university students, I’m been really worrying about it. I’ve had to stop watching the news as it was making me very anxious.”

Dr Ananta Dave, a psychiatrist and medical director at Lincolnshire Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, said Asians who live in areas of deprivation, multi-generation households and hold key worker frontline roles could also be experiencing increased stress. “All these factors could make (Asians) more vulnerable to having mental health problems or a greater emotional impact due to Covid,” she told Eastern Eye.

Dr Dave said mental health support should be prioritised on par with prevention of coronavirus infection. “We give so much importance to guidance on preventing Covid, but I think we need to think of equal protective mechanisms for mental health problems as well,” she told Eastern Eye. “If that is prioritised equally within the system, then I think we can find the answers.”

Some experts have called for more diversity among mental health counsellors or in services catering to ethnic minorities. Children’s charity Barnardo’s established a helpline specifically for ethnic minorities last year.

Ahmed Lambat is the manager of charity LMCP, an organisation supporting community development in Manchester. It has worked with south Asian females with mental health needs since the 1990s.

LMCP found talking therapy was not well understood by some BAME groups. Those who provide these services need systems, processes and culturally competent staff to address the barriers faced by minorities, Lambat said.

“The feedback from those we refer for talking therapies is that they want to deal directly with the counsellor or therapist rather than an interpreter as they believe that things are lost in translation,” Lambat explained to Eastern Eye. “They prefer the professional to be of the same gender and someone who understands their culture and religion.”

Dr Dave also emphasised the importance of services delivering culturally sensitive and empathic support. Grief, loss and trauma were very culturally derived entities, she said, so a one-size-fits-all approach would not work. “Counselling services and bereavement support services do need to be able to cater to a range of requirements,” she said.

Kam Bhui, who is professor of psychiatry at the University of Oxford, agreed there needed to be increased recruitment of counsellors and therapists from diverse backgrounds who could improve the fit of what was provided for patients from ethnic communities.

He did, however, acknowledge that progress had been made to accommodate individuals from different backgrounds. “Therapists and counsellors are now getting better at working with people of diverse religious beliefs and cultures, and so if you are seeking a more specialist service to help you, do ask for guidance,” he told Eastern Eye, adding: “Regrettably there are not enough of these, and most are in the voluntary sectors.”

He said it was imperative that individuals discuss what sort of service and therapist they believe would help. This could be a counsellor with understanding of their cultural needs, or someone who could speak the same language. “Even if a special service is not possible, discussing it makes it more likely you benefit as your counsellor and therapist will understand your concerns,” the academic, whose expertise lies in cultural psychiatry and ethnic disparities in psychiatric disorders, said.

Gurch Randhawa, professor of diversity in public health at the University of Bedfordshire, agreed that mental health service providers should offer flexibility to ensure all communities benefit from early access to support.

Though Prof Bhugra said diverse counsellors gave a message about accessibility of services, he worried they could start to take an “increasingly narrow focus”.

Demand on mental health services has been particularly high during the pandemic. Last month, NHS data showed its mental health services had never been in higher demand. Further findings by the Centre for Mental Health last month estimated 10 million Britons are currently in need of new or additional mental health supports as a result of the coronavirus crisis.

Access to private health care is proving difficult too. Ahuja said she has been seeing a counsellor since December for health reasons unrelated to coronavirus. Despite looking for private counselling services, she still struggled to find an available therapist. “I was shocked that even the private councillors are busy,” she admitted. “(When I approached them last year), they all said their diaries were full. It’s quite difficult to get access to them, even the private ones.”

NHS England did not respond to a request for comment from Eastern Eye.

*Name has been changed to protect identity

For mental health support or advice, call the Samaritans on 116 123. See NHS Every Mind Matters for more.

Heehs describes two principal approaches to biographyAMG

Heehs describes two principal approaches to biographyAMG