THIS year was literally one of two halves in the British government.

Rishi Sunak and Sir Keir Starmer each had six months in Downing Street, give or take a handful of days in July. Yet this was the year of governing anxiously.

January to May were months when not much governing got done under Sunak. Parliament spent three months declaring Rwanda safe for asylum, over court objections, but nobody was sent to Africa.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt spent another £10 billion in March on taking another 2p off national insurance, but nobody seemed to notice. Having a former prime minister, David Cameron, as foreign secretary, did give the UK an energetic diplomatic presence, though a breakthrough in the Middle East remained elusive.

At home, the government left every difficult decision it could – from settling public sector strikes to prisons bursting at the seams – to its postelection successor.

Sunak’s last big decision as prime minister was, in essence, whether his short premiership would end in May or July, October or December. In office, but with power draining away, he chose to get out a few months before he had to.

Hopes of gradual economic improvement were outpaced by an unhappy Conservative party’s descent into ungovernability. There was little purpose – and no joy – in clinging on. May’s local elections confirmed the Tories were heading for defeat, but suicide-by-electorate still seemed the more attractive option.

Sunak’s election announcement somehow caught his own party off guard. The Conservatives stabilised their campaign by tacitly admitting they were unlikely to win, and warning of a Labour supermajority. Twentyfour per cent of the vote and 121 seats somehow felt like a reprieve.

Labour’s one-word slogan, ‘change’, secured a historic landslide with little fanfare, but the lowest winning share of the vote in modern times. A campaign perfectly pitched to gain marginal seats shed half a million of the Labour voters the party was largely taking for granted. Much of the election drama came from the smaller parties – with the Liberal Democrats, Reform, Greens and independents all jubilant at breaking new ground.

The geographic breadth of Labour’s victory gives it an interest in bridging Britain’s social divides if it can find the story and voice to do so.

Six days of rioting after the Southport tragedy had seen the government rapidly restore order and condemn the racist violence. How far it has a strategy to deal with the underlying causes of disorder, by building social cohesion, will be one key test in 2025.

Starmer’s character appears better suited to governing than campaigning, but Labour found the transition to power hard.

July to September were, mostly, three more months when little governing got done. The false start, in a distracted, dysfunctional and divided Downing Street, saw a major overhaul in October. Starmer charged his new political chief of staff, Morgan McSweeney, with getting the show on the road. Chancellor Rachel Reeves delivered a Labour budget, increasing taxes by more than she had to, so there was money to spend on the NHS too.

The Conservative members got the leader they wanted in Kemi Badenoch, after the party’s MPs almost turned the contest into a farce with tactical games. But whether Badenoch is given the chance to fight the next general election is an open question, depending on how the next two years go.

November’s record net migration numbers saw Starmer decide to keep punching the Tory bruise over their record. In 2025, once numbers fall significantly, the prime minister will need a new argument to describe the balance of his own government’s policy on immigration.

The government’s first six months have seemed randomly defined – by cuts to winter fuel payments, arguments with farmers and the agonised debate over assisted dying.

Labour ministers believe the government’s fate will depend primarily on whether it can produce noticeable improvements in living standards, the NHS and the condition of the country. The election of Donald Trump as US president will make governing harder – certainly in multilateral forums, and perhaps, economically, too.

What happens next? Nobody can know for sure. This month was the fifth anniversary of the December 2019 general election – hailed as a major “realignment” and an era of Tory dominance. This has been the sugar-rush decade in British politics.

Starmer’s challenge is to use his large majority to show that a more stable governing politics is possible. But one unknown may be how far our political culture could adapt if it was. There was more media attention on Badenoch’s distaste for sandwiches last week than the overhaul of English local government.

The credulity given to media fantasies of Nigel Farage becoming prime minister – as if Britain hankers for the politics of Trump and Elon Musk – partly reflects an interest in talking about anything, except policy.

But, after the year of governing anxiously, 2025 may see a shift in gear to the grind of trying to govern better.

(The author is the director of British Future)

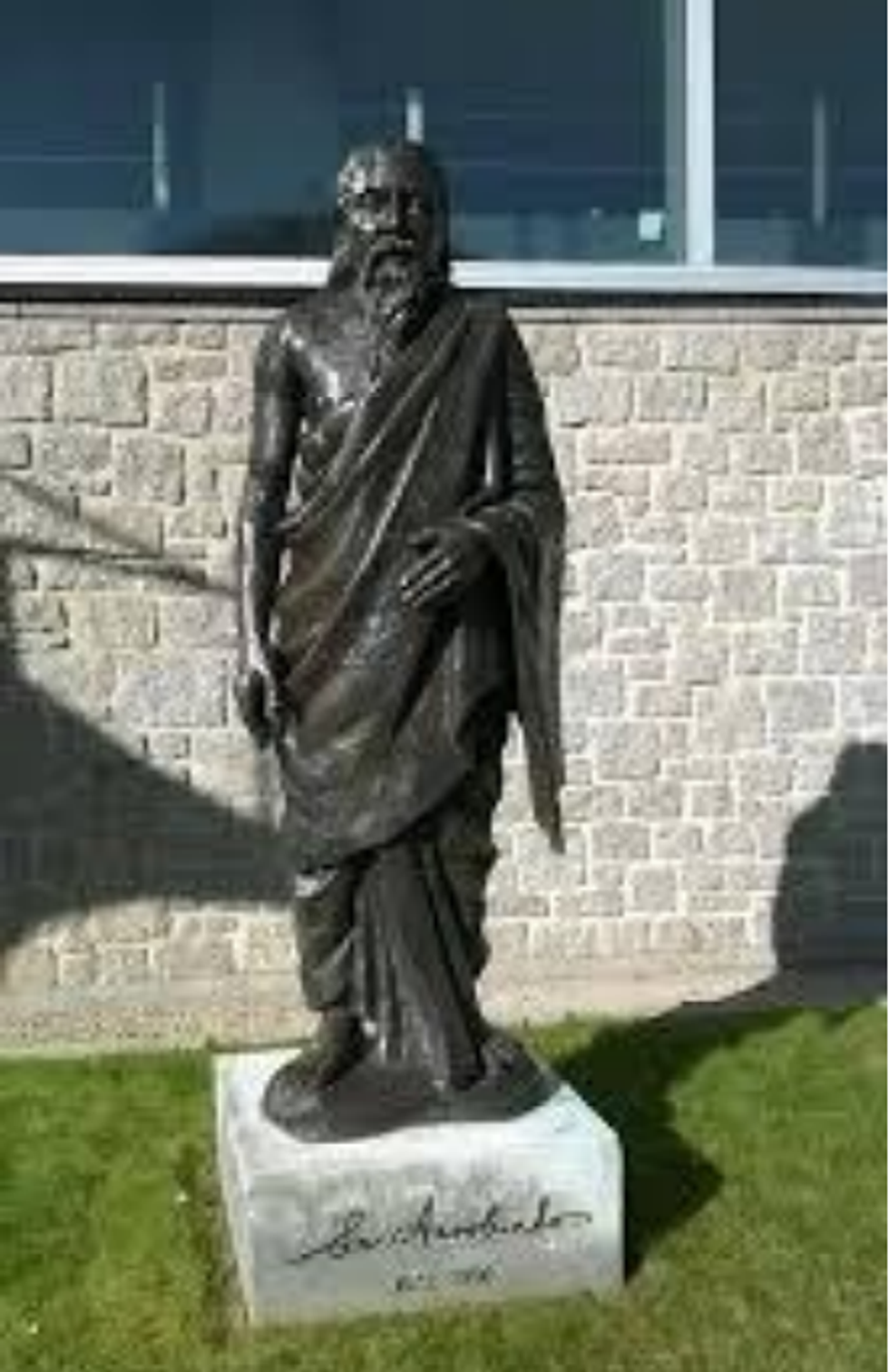

Heehs describes two principal approaches to biographyAMG

Heehs describes two principal approaches to biographyAMG

David Beckham wearing a David Austin Roses "King's Rose" speaks with King Charles III during a visit to the RHS Chelsea Flower Show at Royal Hospital Chelsea on May 20, 2025Getty Images

David Beckham wearing a David Austin Roses "King's Rose" speaks with King Charles III during a visit to the RHS Chelsea Flower Show at Royal Hospital Chelsea on May 20, 2025Getty Images