By Julie Summers

A FEW years ago, I appeared in The Sunday Times list of 50 top historians.

I was one of only four women, which was somewhat depressing. Scanning the list the other day I noted that all the historians were white. History, and especially the history of the two world wars, has been written by white men. Some of it is outstanding, but it is almost always seen through the lens of Western Europe.

When I wrote about my grandfather’s war, I was describing a theatre that was never taught at school and which I had only seen in movies. Colonel Philip Toosey, later Brigadier Sir Philip Toosey, was evacuated from Dunkirk in 1940 and captured by the Japanese in Singapore in 1942. He spent three and a half years in captivity on the infamous Thailand Burma Railway where he and 60,000 Allied prisoners and 250,000 Tamil, Malay and Burmese civilians built a 415km stretch of railway from Bangkok in the east to Moulmein in the west. The cost in lives was terrible. More than 12,000 Allied prisoners and 83,000 civilian labourers died in the construction of the so-called Death Railway.

The story was immortalised in the 1957 war film Bridge over the River Kwai with Alec Guinness playing the role of the bone-headed Colonel Nicholson who was in charge of the bridge camp. This was a role my grandfather had played in real life, the difference being that he was no collaborator. His single-minded focus was not on building a bridge, but on keeping his men alive and getting as many of them home as possible.

How did I find the stories about my grandfather? He refused ever to speak about his time in Thailand saying we children would never understand. But he did talk about both world wars in general terms. I remember, as a little girl, hearing him state firmly: ‘We would never have won the First World War without the Gurkhas.’ It made quite an impression on me and I have never forgotten his clear message that the British Army was not made up just of white soldiers.

Towards the end of his life, he was persuaded by his son, Patrick, to record his wartime experiences. Patrick was concerned history would judge him unfairly because the film fictionalised his life in the POW camps in an inaccurate way. Over 18 months, although desperately weak, he made 30 hours of tape recordings about his life, including the pre-war years when he was growing up in Liverpool. It was the focus on his wartime activities that really interested me and eventually I wrote a biography, The Colonel of Tamarkan, that corrected some of the myths in the Bridge over the River Kwai and told his story.

After the war he travelled all over the world for his business, spending weeks and sometimes months in Africa. He told us grandchildren, ‘you should never judge a person by the colour of their skin but by what they contribute to the world’. It was a belief that had stood him in good stead in the fight for Singapore, where he fought alongside Indian soldiers, and in the prison camps where over half the men under his command were from the then Dutch East Indies.

When I wrote my grandfather’s story, I was struck that in doing so I gave him a place in history, albeit a small one. And I gave his family a stake in his remarkable achievements. In writing the book We are the Legion for the Royal British Legion’s centenary, I have come across many stories that give vitality and life to men whose names I discovered in the Legion’s archive material. In the course of this research, I encountered Dr Irfan Malik and the remarkable story of his ancestral village which was gifted a large canon in grateful thanks for the commitment of some 360 of its men in the First World War. Dr Malik has brought the story of the village and its great contribution to the British Army in both world wars to the fore. It has helped to make him feel the Remembrance poppy has meaning for him.

I feel passionately that we have to own our family’s stories. In researching and recording them, we can add layer after tiny layer of colour onto the rich tapestry which is our shared heritage. I would encourage anyone who is at all interested in finding out what their forebears did in both world wars to start the thrilling process of digging around in archives. These are not dusty places run by old men in cardigans and round glasses (though, delightfully, one was in my grandfather’s case) but are living repositories of all our stories. They can be found in trunks in attics, in libraries and museums, in council registers, on the websites of countless local histories.

It should not be that the history of the two world wars is written only from a Western perspective by white men, and a few women. We need the stories of your families. Do not think they have to be famous to be relevant. History is made up of ordinary people doing remarkable things in extraordinary times. Let us hear about the heroes and heroines who came from all over the Indian subcontinent and contributed to the defeat of the enemy both in 1914-18 and 1939-45. The numbers are astonishing; 100,000 Gurkhas fought on the Western Front in the First World War. By 1945 more than 2.5 million men and women had volunteered to fight in the Second World War.

General Auchinleck, who commanded the Indian Forces in the Middle East, said: ‘The British couldn’t have come through both wars if they hadn’t had the Indian Army.’ Do let us hear those family stories.

Historian Julie Summers is the author of 14 books, including We Are The Legion: The Royal British Legion at 100, which will be published on May 15.

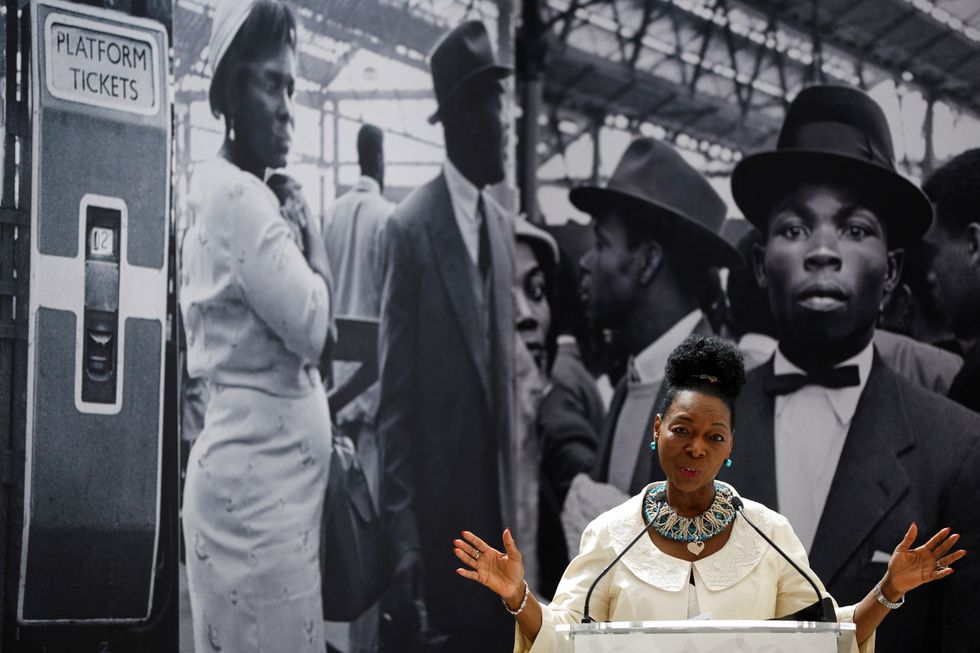

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’

Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’ Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’

Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’ Mahira Khan

Mahira Khan ‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience

‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’

Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’  John Abraham

John Abraham Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal

Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal  Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut

Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut Sana Yousuf

Sana Yousuf