PRIME MINISTER Sir Keir Starmer was, if anything, a little late in coming to the party when he accorded formal recognition of a Palestinian state last Sunday (21).

India did so on November 18, 1988, two days after Pakistan and Bangladesh.

Starmer has followed most of the rest of the world.

His words were clear: “So today, to revive the hope of peace and a two-state solution, I state clearly as prime minister of this great country that the United Kingdom formally recognises the state of Palestine. We recognised the state of Israel more than 75 years ago, as a homeland for the Jewish people. Today, we join more than 150 countries who recognise a Palestinian state, a pledge to the Palestinian and Israeli people that there can be a better future.”

The UK’s move coincided with similar recognition from Canada, Australia and Portugal. Other countries also joining the list are Belgium, France, Luxembourg, Malta and possibly New Zealand and Liechtenstein.

Although Starmer said “we recognised the state of Israel more than 75 years ago”, it would be more accurate to state that the UK was the prime mover in the creation of “a homeland for the Jewish people” in 1948.

Therefore, the UK’s formal recognition of a Palestinian state is not just one more country joining a long list. It has moral and international significance.

To be sure, there is a tiny minority of people in the UK who argue Starmer is in the wrong, but a referendum would show that probably 75-90 per cent of the British people think he is in the right.

Most people are persuaded that in response to Hamas’s brutal killing on October 7, 2023, of 1,195 people (among them 736 Israeli citizens, including 38 children, 79 foreign nationals and 379 members of the security forces) and the taking of about 250 hostages, Israel has and is continuing to commit genocide in Gaza. This is acknowledged by Jewish people brave enough to speak out.

Omer Bartov can hardly be accused of being anti-Semitic. He is Dean’s professor of Holocaust and genocide studies at Brown University in the US.

His article, Never Again, in the New York Times in July, stated: “I’m a Genocide Scholar. I Know It When I See It.”

He wrote: “My inescapable conclusion has become that Israel is committing genocide against the Palestinian people. Having grown up in a Zionist home, lived the first half of my life in Israel, served in the I.D.F. as a soldier and officer and spent most of my career researching and writing on war crimes and the Holocaust, this was a painful conclusion to reach, and one that I resisted as long as I could. But I have been teaching classes on genocide for a quarter of a century. I can recognise one when I see one.”

He pointed out: “This is not just my conclusion. A growing number of experts in genocide studies and international law have concluded that Israel’s actions can only be defined as genocide.”

Last week, a UN commission of inquiry also said Israel had committed genocide in Gaza. Across a three-page resolution, the International Association of Genocide Scholars (IAGS) presented a litany of actions undertaken by Israel throughout the 22-month-long war that it recognises as constituting genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity.

And earlier this month, Israel’s Supreme Court ruled that the state is failing to provide adequate food to Palestinian prisoners, and must take steps to improve their nutrition. The three-judge bench said the government was legally obliged to provide prisoners with enough nutrition to ensure “a basic level of existence”.

Again, the judges can hardly be accused of being anti-Semitic.

The United States is one of the few countries that continues to give unquestioning support to Israel, which it considers its main ally in the region.

Meanwhile, for the British people, the Gaza war is no longer something far away. As Starmer said: “I know the strength of feeling that this provokes. We have seen it on our streets, in our schools, in conversations we’ve had with friends and family. It has created division. Some have used it to stoke hatred and fear, but that solves nothing.”

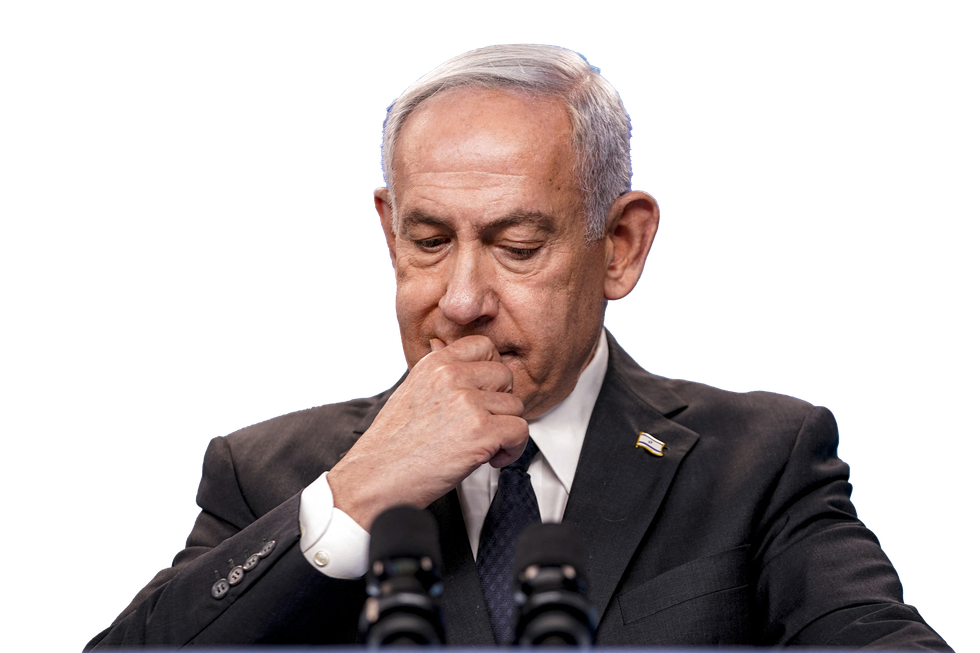

Backed by the US, Israel prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s government has the military power to destroy Gaza completely, which it has pretty much done, kill or starve to death a significant part of its population, and occupy the West Bank.

But there is a price to pay for that – apart from international condemnation which Israel can choose to ignore. It does mean there is no long-term peace for the people of Israel who will have to resign themselves to war without end.

It may be wiser to accept a Palestinian state, help to rebuild Gaza, pull out of the illegal settlements in the West Bank – and, at least, seriously test whether this new path works.