TO HER party, Suella Braverman was able to say things which the prime minister thought but could not voice.

To his critics, Rishi Sunak was the man who stabbed Boris Johnson in the back and someone whose party did not elect him as its leader.

Braverman gave him a shield and a way to keep the right quiet. Now, though, Sunak has got rid of the right’s standard bearer.

According to sources who have spoken to Eastern Eye, questions remain. How did Braverman get away with what she did for so long, and why did the prime minister hesitate so publicly to remove her from one of the great offices of state?

“Don’t forget that Rishi owed her,” said one south Asian parliamentarian. “He had already lost against Liz Truss, and when she resigned, Rishi faced another fight against Penny Mordaunt.

“The last thing he needed was another bloody nose from the members. Suella backed him, and that was a game changer.”

Sue-Ellen Cassiana Braverman KC, was born in Harrow, northwest London, and named after one of the female characters in the US TV soap, Dallas.

Her parents – Uma, a Hindu, and Christie Fernandes, a Christian – emigrated to the UK from Mauritius and Kenya, respectively.

Braverman’s mother was an NHS nurse and Tory councillor who also ran to become an MP.

The former home secretary read law at Cambridge and was chair of the university’s Conservative Association. In 2005, she stood against Keith Vaz in Leicester East, but lost by about 16,000 votes.

It would be another 10 years before Suella Fernandes, as she was then, won the safe Tory seat of Fareham in Hampshire.

In 2016, she was a firm Brexiteer, reflecting the wishes of her constituents.

The following year, she became the chair of the European Research Group, made up of pro-leave Conservative MPs.

After the 2017 general election she was appointed as a junior minister by Theresa May, but she resigned the following year. Also in 2018, the Buddhist married Rael Braverman, a Jew, at the House of Commons. Their children George and Gabriella were born in 2019 and 2021.

When Liz Truss became prime minister in September 2022, she appointed Braverman as the home secretary, responsible for overseeing UK borders and policing.

At a fringe event at that year’s party conference, she said, “I would love a front page of the Telegraph with a plane taking off to Rwanda. That is my dream, it’s my obsession.”

Around the same time, she used her oratory skills to great effect.

“I am afraid that it is the Labour party, the Lib Dems, the coalition of chaos, the Guardian-reading, tofu-eating wokerati and, dare I say, the anti-growth coalition that we have to thank for the disruption we are seeing on our roads today,” she told parliament.

But hubris is the downfall of many.

The next day, she resigned after sending an official document from her personal email, which is against the rules.

Yet, like a game of snakes and ladders, six days afterwards, Sunak appointed her as … home secretary, where an emboldened Braverman never shied away from controversy.

In March 2023, she said with a straight face, “There are 100 million people around the world who could qualify for protection under our current laws.

“Let us be clear – they are coming here.”

When questioned about the figure, Braverman told the Daily Mail, there was “likely billions” eager to come to the UK.

The problem with that statement is the experts do not agree – the UK receives far fewer asylum seekers than other countries.

Lest we forget that Braverman’s parents were immigrants to a welcoming Britain, she concluded in September (26) that “multiculturalism makes no demands of the incomer to integrate – it has failed.”

Many would have heard alarm bells when No 10 and her colleagues distanced themselves from their comments, but not Braverman.

She ploughed on regardless, this time targeting pro-Palestinian demonstrators, claiming their chants amounted to anti-Semitic attacks.

“There’s only one way to describe those marches – they are hate marches,” she declared.

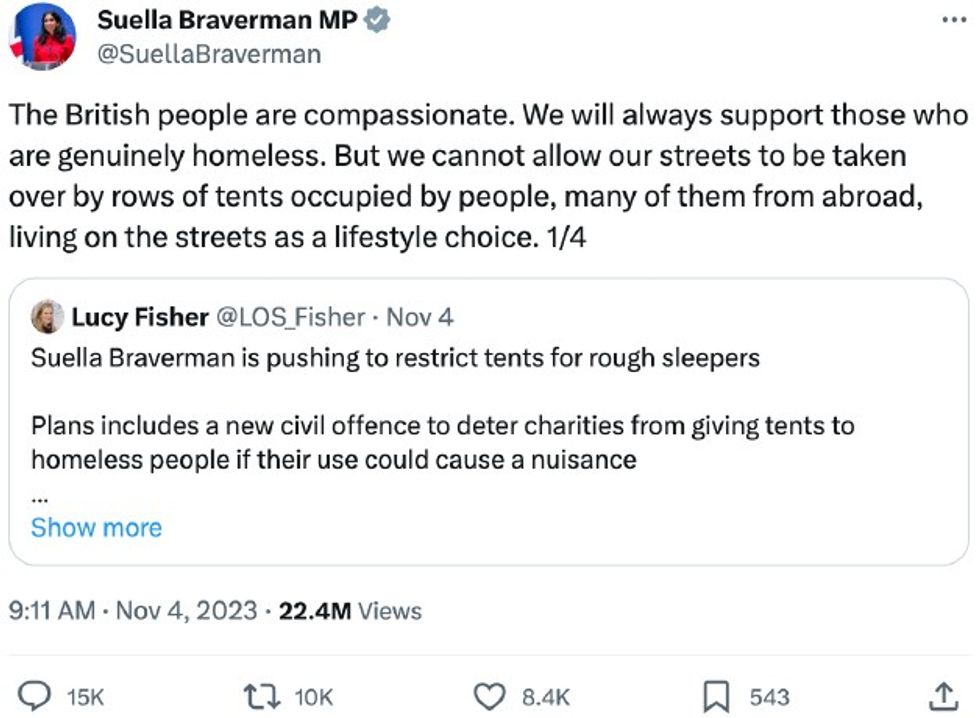

Then came that infamous post on social media which angered many an ordinary Tory.

“We cannot allow our streets to be taken over by rows of tents occupied by people, many of them from abroad, living on the streets as a lifestyle choice.”

Sources who spoke to Eastern Eye were incandescent with rage – telling this newspaper that Braverman had resurrected the moniker of Conservatives being the “nasty party”.

Finally, the Times article which ended her tenure as home secretary, where she accused the police of playing favourites, being harsher on the right than the left.

Last Saturday (11), London saw membes of the far-right English Defence League (EDL) descend on the capital, causing mayhem.

The man who led the Metropolitan Police operation, Assistant Commissioner Matt Twist said, “The extreme violence from the right-wing protestors towards the police today was extraordinary and deeply concerning.

“They arrived early, stating they were there to protect monuments, but some were already intoxicated, aggressive and clearly looking for confrontation.

“This group were largely football hooligans from across the UK, and spent most of the day attacking or threatening officers who were seeking to prevent them being able to confront the main march.

“Many in these groups were stopped and searched and weapons including a knife, a baton and knuckleduster were found as well as class A drugs.”

And yet Braverman concentrated her fire on the 300,000 pro-Palestinian demonstrators.

“This can’t go on,” she posted on X, formerly Twitter. “Week by week, the streets of London are being polluted by hate, violence, and antisemitism.

“Members of the public are being mobbed and intimidated.

“Jewish people in particular feel threatened. “Further action is necessary.”

For now, Braverman will not be the one who will influence policing or migration in the country.

But only a fool would be writing her political obituary just yet.

If Lord Cameron has shown one thing, it is that politicians come, politicians go…only to return when people least expect it.