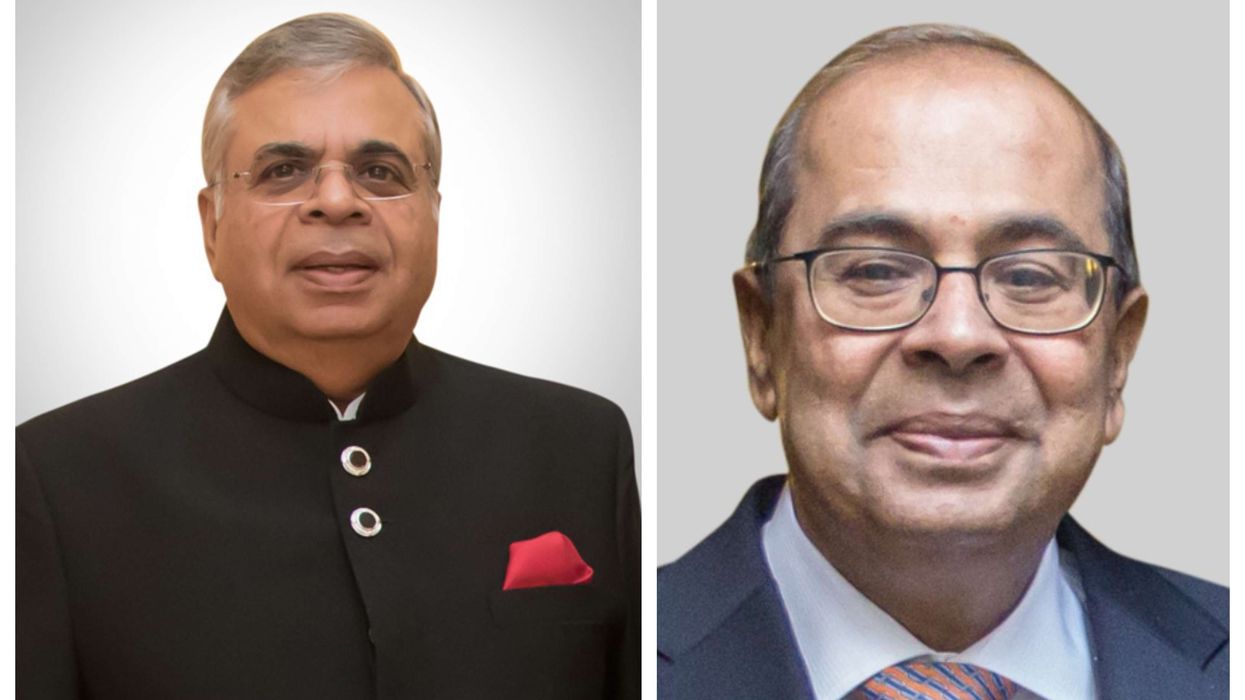

WITHOUT doubt, Sir Rabinder Singh is one of the finest legal minds in Britain today. That might sound an extraordinarily bold statement but two factors about Sir Rabinder really stick out from the outset.

Known more formally as The Right Honourable Lord Justice Singh and Lord Justice Singh, it was announced in September last year that he would be president of the independent body that adjudicates over complaints about surveillance activities of the intelligence services.

This tribunal process was created after the 2000 Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (IPA) to ensure greater accountability. Lord Chief Justice Burnett of Maldon declared: “The appointment of a lord justice of appeal as president of the tribunal ensures that the tribunals is headed by a senior judge of equivalent status to the investigatory powers commissioner.

Lord Justice Singh brings a wealth of experience in the judiciary and expertise in public law, which will be crucial to the tribunal’s vital role in hearing complaints concerning the use of investigatory powers.” Basically, Lord Justice Singh has a role in bringing the intelligence services to book, if they overstep the mark, and the fact that he has been handed this responsibility shows the high regard with which he is held in the judiciary.

He was made a high court judge at just 39 – becoming the youngest ever to be appointed. Lord Justice Singh delivered the Kay Everett Memorial Lecture at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in February, where he opened up about his work as the president of the Investigatory Powers Tribunal.

Kay Everett was a highflying city lawyer who gave up commercial law to retrain at SOAS and specialise in human rights and immigration law. She died tragically young of cancer, aged 43, in 2016 and a memorial lecture was created in her name.

Lord Justice Singh paid warm tribute to her and said: “I doubt if there are many others who have the courage to do what she did.” Generally, Lord Justice Singh sets out the background and provides a brief overview of the history of intelligence services on these islands and the various pieces of legislation that have impacted the operation of those services and the rule of law.

The essential point is that the intelligence services are not above the law, and the Investigatory Powers Tribunal is there to prevent and check abuses of power and so forth.

What is perhaps telling is Lord Justice Singh’s emphasis on human rights and that these must be balanced with requisite security concerns, and the responsibility of the state to protect and defend its citizens, most noticeably from physical (or even more pertinently now, cyber) attacks, both of the terrorist nature and more broadly by hostile foreign states.

The lecture deals with details and processes but at the nub is the question of human rights and just how much protection do we have as ordinary citizens? In his closing lecture remarks Lord Justice Singh quoted Sir David Omand, a former director of GCHQ (now also recognised formally in the statute book) and a highly experienced civil servant, who was the first intelligence and security coordinator and reported to the prime minister. Now a visiting professor at King’s College London, he has written extensively about ethics and the security services.

Lord Justice Singh chose to quote him at the end in some length, and it gives an insight into how a judge such as Sir Rabinder considers issues before him. “Human rights are a public good, as is security,” Lord Justice Singh, said quoting Sir David.

“The balance to be struck by a wise government is not between security and rights, as if to argue that by suspending human rights security could be assured. The balance has to be found within the framework of rights, recognising the fundamental right to life, with the legitimate expectation of being protected from the state from threats to oneself and one’s family, an important right that in some circumstance must be given more weight than other rights, such as the right to privacy of personal and family life.”

It is all about balance and preserving an individual’s rights while protecting society. It is up to judges such as Lord Justice Singh to draw boundaries and hold the security services to account, when others perceive unfair attention and inquiry, perhaps leading to criminal (terrorist) charges.

In July, in a challenge from rights’ group Liberty, Lord Justice Singh and Mr Justice Holgate ruled that IPA, referred to in some parts of the media as a ‘snoopers’ charter’ did not present an undue or excessive erosion of rights – or the belief held by the plaintiffs that confidential journalistic sources could be compromised.

The judges simply conclude that the “totality of the suite of interlocking safeguards”, contained within the act meant human rights were not being violated. Needless to say Liberty didn’t agree and has filed an appeal.

The IPA allows for ‘bulk secret surveillance’ and journalists, argued Liberty, were especially at risk. For the judges, crudely there were enough safeguards within the act to allow them to intervene if required. Sir Rabinder Singh was born in New Delhi in 1964 and came to Britain as a child.

He won a scholarship to the private Bristol Grammar School and studied law at Cambridge and passed out with a double first. He pursued his legal education in the US, studying for an LLM at the University of California at Berkeley.

Despite his academic prowess, he was unable to continue his ascent into the profession because he didn’t have the funds (to attain pupillage immediately) and started teaching law at the University of Nottingham, before winning a scholarship to attend the Inns of Court. He qualified (was called to bar, as it is termed) in 1989.

He became a Queens Counsel (QC) in 2002 and was a founder member of Matrix Chambers (and a colleague of Cherie Blair). He continued to teach after practising and was a part-time law lecturer at LSE (20032009). He remains the highest legal officer in the land with an ethnic background.