by STEVE ROSE

THE de-politicisation of the actions of the suspect in the Christchurch mosque attacks demonstrates how discussions in the mainstream press remain stubborn, reflexive and solipsistic.

They are not reflective nor introspective. Think pieces which place Islamophobia in quotation marks following the tragic events of last week deserve scorn, not editorial approval.

Rather, we should ask: how did we arrive here? But that’s just one aspect of the problem, as the echo chambers which inspire such ideological devotion find validation in various forms from main- stream figures and sources which ‘other’ Muslims as cultural threats who deserve their marginalisation. Islamophobia and anti-Muslim hatred are real, growing problems that go beyond criminal acts, from discriminatory attitudes and normalised bigotries which harm the mobility and employment prospects of Muslims, to the disproportionate use of police and counter-terror powers.

Much of my job involves trying to understand what motivates the far-right, but how accessible and mainstream their talking points have become, not just in 2019 or even a decade ago. History compels us to look further. Both the Conservative party under Margaret Thatcher, and New Labour under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, are guilty of main- streaming the far-right when politically expedient.

Was Brenton Tarrant radicalised on his tour of Europe? His self-aggrandising and racist screeds reflect a broader neurosis in the European, North America, and Australasian radical right. The obsession with demographics and mythologised narratives linking Muslims more broadly to criminality populate tabloids. US president Donald Trump famously told CNN in 2016: ‘I think Islam hates us’.

Tarrant, like other far-right terrorists has welded himself to a grander narrative: of a collective struggle against invaders, be they Muslim, Jewish, or other minority groups which span centuries of violent European history. The misuse of history helps to further a deeper sense of an impending civil war, or clash of civilisations; where individuals feel ob- ligated to assert their racialised rage at Muslims as a form of pre-emptive violence, where their justifications are couched in mainstream talking points and news articles. The conclusion of which, in this tragic example, is genocidal. It’s no coincidence that his musical choices reflected the propaganda of genocidal regimes of Nazi Germany and Rado- van Karadžic, the “Balkans butcher”.

Where does this narcissistic idea of ‘revenge’ stem from? The academic Sara Ahmed posits that fascist forms of love are a product of ‘narcissistic whiteness’ which inverts hatred and racial violence into acts of redemption born from a love of the self (whiteness) and the imagined ideal of the nation- state. This narrative of love, from fascists and the extreme far-right, centers the risk the in-group faces from the out-group. It’s why the infamous neo-Nazi slogan ‘14 words’ – one of the clearest examples of this narcissism was written in Tarrant’s manifesto, and on his weapon.

Ahmed further states that such a reversal of logic places ‘race-mixing’ as a form of hatred. This point also extends to the hatred Tarrant applies to white individuals who have converted to Islam. Such actions are a form of betrayal, a betrayal drenched in racialised language. How then could the adage ‘Is- lam is not a race’ be true?

Tell MAMA continues to document how racialised ideas about Muslims see white converts referred to ‘P***s’, as racialisation, after all, incorporates ‘cultural factors in addition to traditional, physical markers of race and ethnicity’.

In Tarrant’s native Australia, the senate almost voted in favour of a bill full of far-right talking points, including the now infamous phrase ‘It’s Okay to be White’. Nor is it an accident that Tarrant made this gesture when in court.

Tell MAMA has seen a rise in racist incidents fol- lowing the terror attack in Christchurch, on social media and offline. This reality should shock us into changing attitudes and challenging hatred. Spreading Islamophobia or anti-Muslim stereotypes should not be rewarded with column spaces. Nor should accountability for one’s actions or comments result in half-hearted apologies. We can and should as- pire to do better. And that extends to centring the voices and lived experiences of Muslims both in mainstream media outlets and in politics.

- Steve Rose writes about Islamophobia and the far-right for Tell MAMA and Faith Matters.

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’

Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’ Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’

Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’ Mahira Khan

Mahira Khan ‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience

‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’

Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’  John Abraham

John Abraham Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal

Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal  Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut

Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut Sana Yousuf

Sana Yousuf

Shraddha Jain

Shraddha Jain Arundhati Roy

Arundhati Roy William Dalrymple and Onjali Q Rauf

William Dalrymple and Onjali Q Rauf Ravie Dubey and Sargun Mehta

Ravie Dubey and Sargun Mehta Money Back Guarantee

Money Back Guarantee Homebound

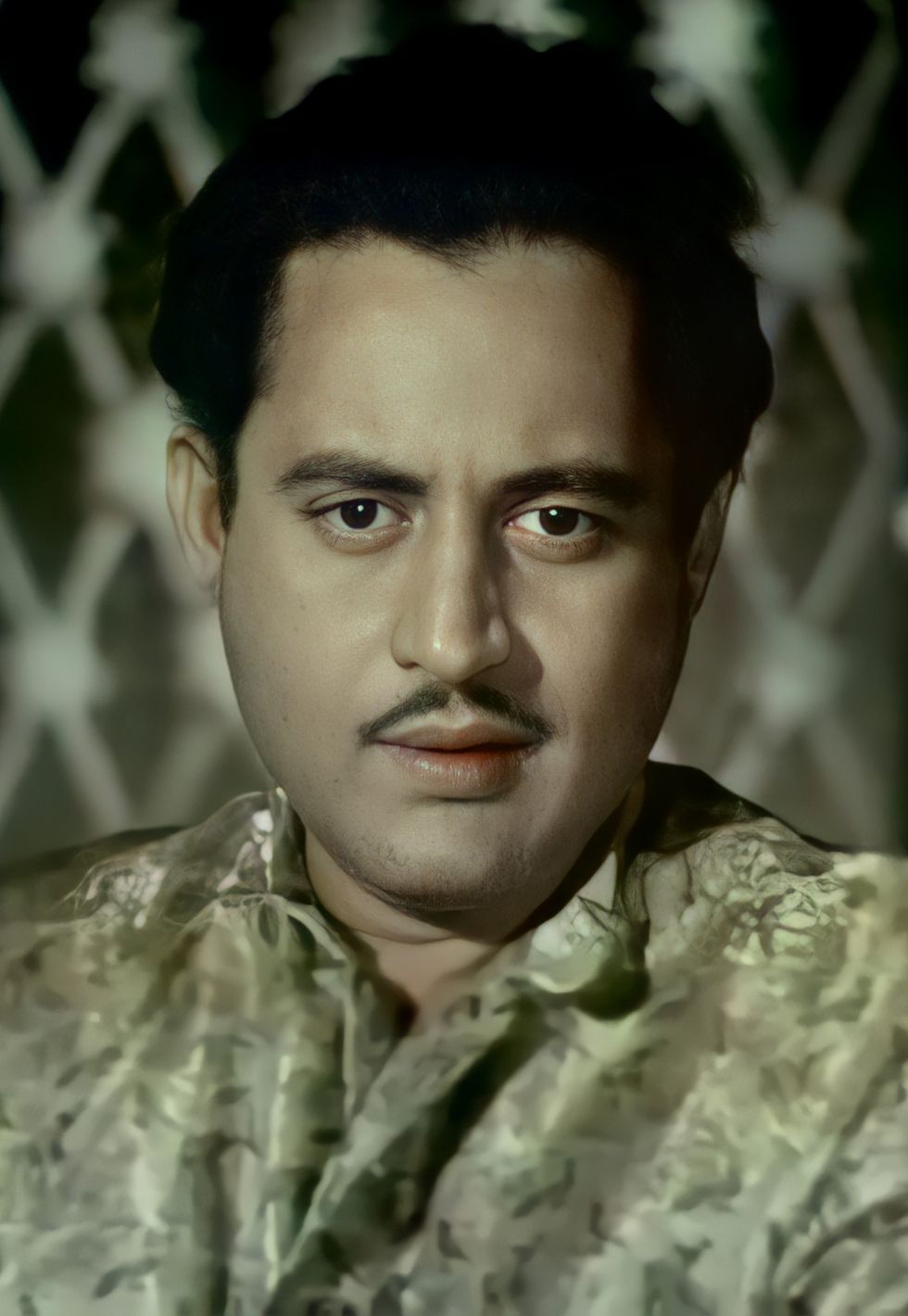

Homebound Guru Dutt in Chaudhvin Ka Chand

Guru Dutt in Chaudhvin Ka Chand Sarita Choudhury

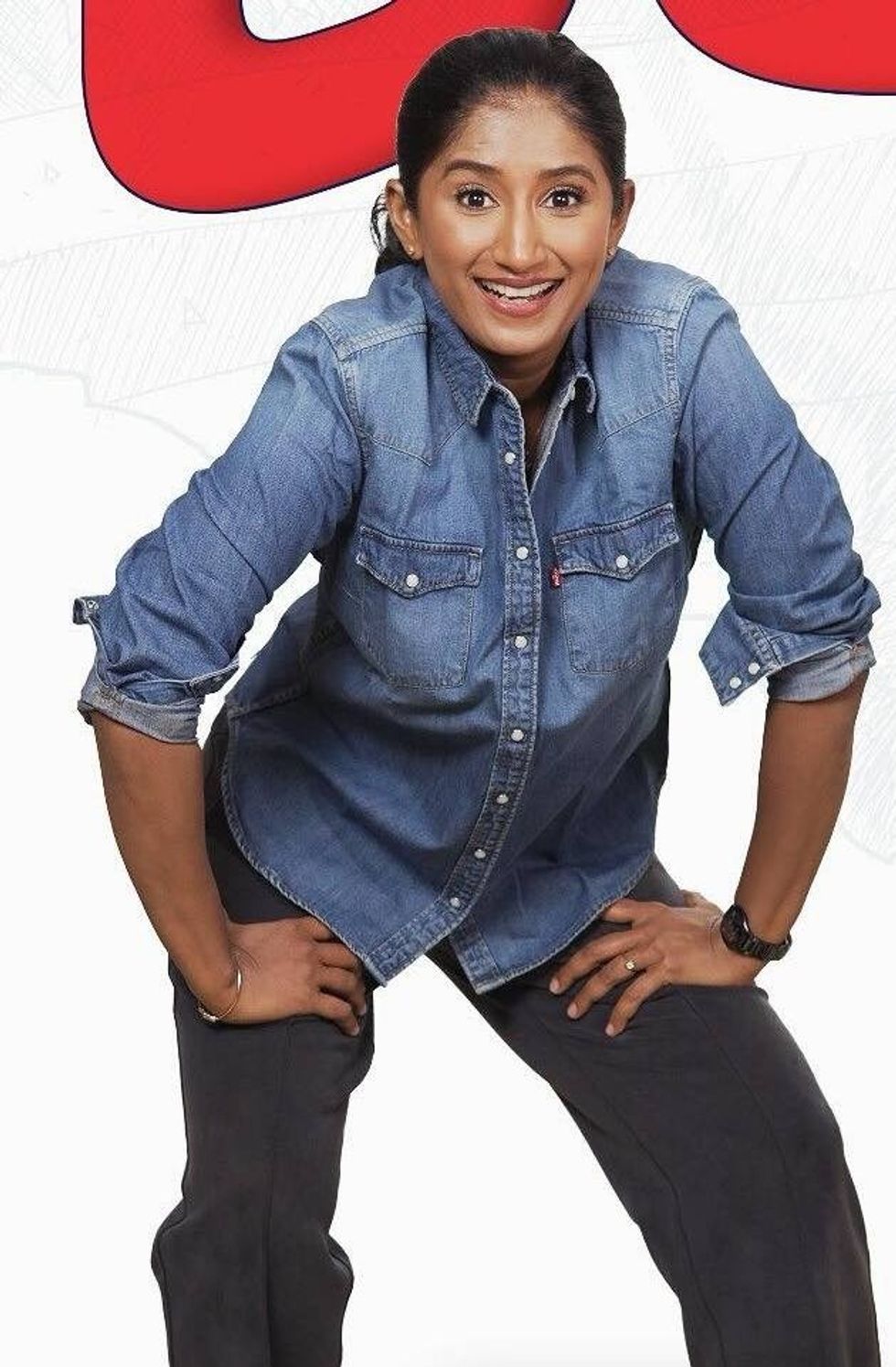

Sarita Choudhury Detective Sherdi

Detective Sherdi

Nigel Farage and Zia Yusuf

Nigel Farage and Zia Yusuf